Much has happened with gene-editing since Contending Modernities’“Out of the Lab” podcast. Despite the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2018 recommendations that gene-editing should be stringently regulated and only used for a limited number of somatic diseases at this time, a surprisingly stunned world witnessed the birth of twin CRISPR-Cas9 edited girls in China in November, with a third baby on deck. Voices across the spectrum—scientific, ethical, theological, policy-oriented—excoriated the researcher, He Jiankui. Repeatedly described as a “rogue scientist,” it now appears that He may have had at least one US collaborator.

Listening to the above commentary, a trained ear might hear a pattern, a subtle but regular pulse, that signals the heart of the matter. Where Adil Najam fears a “gap” between the ethical, policy, and “entrepreneurial realities” surrounding technologies like gene-editing, I would suggest that these are, rather, all neatly aligned.[1] To put it pointedly: the CRISPR conversation makes clear that bioethics, as it has emerged since the 1980s, is a deeply neoliberal project.

This is a big claim—one that can hardly be thoroughly argued in a blogpost. A complete argument would require detailing the intertwined histories of neoliberal economics and bioethics as they emerged post-World War II. Here I will only point to four notes that resonate throughout the literature. When taken together, they sound the dissonant chord of neoliberalism. These are: CRISPR as a technique, concerns about commercialization, dyspepsia about regulation, and the framework of bioethics itself, particularly its understanding of the person.

Neoliberal Bioethics

First, the briefest primer on neoliberalism. Bruce Rogers-Vaughn, in his important book Caring for Souls in the Neoliberal Age, defines neoliberalism as “the free market ideology based on individual liberty and limited government that connected human freedom to the actions of the rational, self-interested actor in the competitive marketplace” (2).[2] Arising in the early 20thcentury, neoliberalism emerged in full force in the late 70’s-early 80’s with the Reagan-Thatcher era and the Washington Consensus. Central tenets include the liberalization of trade barriers, privatization of social services, globalization, and deregulation. In order to limit government, neoliberalism calls for sharply reducing or eliminating social services and welfare programs. The “social” is perceived as a mythic restraint on individual freedom. Neoliberalism aims to maximize the freedom of the individual, homo economicus—a person whose fundamental activity is choice and who chooses the good as she-or-he defines it based on a rational calculation of pure self-interest. Society is little more than an aggregate of autonomous individuals each pursuing their own good. Notably, however, freedom is redefined in market terms.

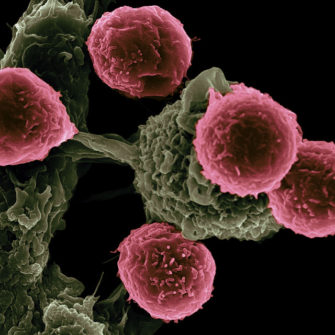

Neoliberalism is not simply an economic theory. It is a cultural project that subtly and pervasively organizes contemporary life. Rogers-Vaughn, in tracing how neoliberalism has transformed psychiatry, provides a template for making visible how it has likewise altered other areas of medicine and clinical research. CRISPR-Cas9 embodies a new approach to thinking about diseases, social problems, and human identity that he refers to as “methodological individualism.” Since roughly 1980, when mental illness was reconceptualized in the DSM-III, through “gene therapy,” stem cell therapies, the BRAIN initiative, neuroscience, and individualized or personalized medicine, a subtle shift has occurred that locates the source of diseases or problems within particular individuals rather than within social or political structures. Illness, here, is conceived as highly individualized, rooted deeply in the nano-loci of personal biology—genes or neural signatures. This new etiological framework drives a search for “biologically-mediated person-specific treatments.”[3] CRISPR envisages the human genome as a biological text that needs “editing.” There lies the problem. Having defined disease as biologically mediated, the medical-industrial complex then hunts for biological interventions that can efficiently fix mistakes that are located at the deepest level of our being—or, via enhancement, that shape our identities.

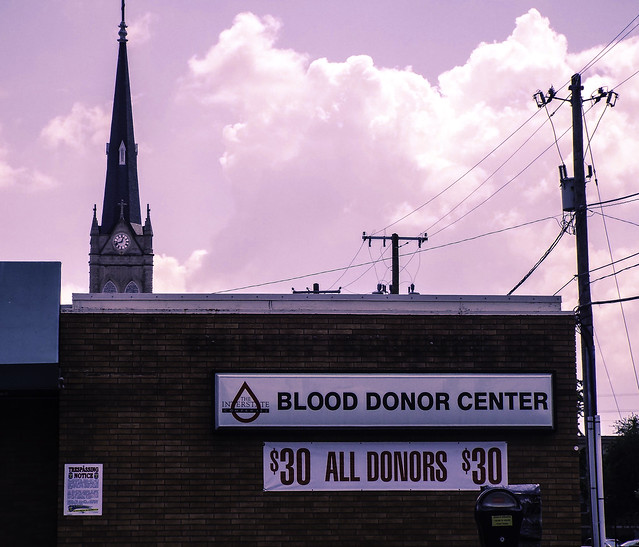

Though justified by the goal of reducing suffering, a second neoliberal commitment catalyzes the hunt: economic efficiency and maximizing profits. In the podcast, Maura Ryan raises concerns about “commercialization.” Aline Kalbian repeatedly refers to CRISPR’s “entrepreneurial aspect” and our free market, competitive context. He Jiankui’s motivation for creating the CRISPR babies was “personal fame and fortune.” Others in the Contending Modernitiesseries raise concerns about commodification. But exorbitant prices, pervasive commodification, and a focus on market share and ROI are not accidental. They are the result of intentional neoliberal policies. The 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act transformed the pharmaceutical market. In 1985, the FDA approved, for the first time, direct-to-consumer marketing for medical products. In 1989, NIH established the Office of Technology Transfer to maximize the financial profits of government-funded research. The list could go on. Moreover, via Gary Becker and the Chicago School, the market extends to an ever-wider array of social realities; the market becomes, in the catchphrase of Freakonomics, “the hidden side of everything.”

Kalbian notes in the podcast that commercial aspects of new medical technologies are not being regulated. David Baltimore, chair of the National Academies’ committee on gene-editing, laments the “failure of self-regulation in the scientific community” in the CRISPR babies case. But we should not be surprised. As Michael Fitzgerald more realistically states in “Out of the Lab”: “regulation gets in their way.” Deregulation, as mentioned earlier, is a central neoliberal platform. Regulations, characterized as the demon of big government, constrain the market’s freedom. Rogers-Vaughn notes a concerted movement, beginning in the late 70s, to make “governments reduce or withdraw laws and rules requiring corporations to consider any purposes other than pursuit of profit.” In the mid-1990s, when I served on the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, Big Pharma was a visible presence at our quarterly meetings, exercising a watchful eye over ethicists or community members who might seek to put limits on R&D.

Almost to a point, current analyses of gene-editing reprise those 1990s debates. CRISPR-Cas9 is essentially gene therapy 2.0. New technologies are more efficient and likely more efficacious than adenovirus vectors. But the same ethical arguments were made in the 1990s as now; the same guidelines were put in place. The bioethical framework has not changed. From the National Academies to ethicists and analysts, the debate remains mapped by beneficence, non-maleficience, justice, and respect for persons, pastiched over a bedrock of utilitarianism. Or…is it respect for persons? As I have narrated elsewhere, 1980 is not only a key moment in the history of neoliberalism. It is also a key moment in bioethics. For in 1979, another subtle but important shift occurred: Belmont’s respect for persons morphed into Beauchamp and Childress’ respect for autonomy.

The “person” as a regulative concept in medical ethics emerged at a particular historical moment: post-War Europe, first gestured at in the Nuremburg Code in 1948.[4] (Is it a coincidence that second phase of neoliberalism begins around 1950?) Imported to the US in the late 1960s after a series of research scandals, “personhood” becomes integrated into the emerging bioethics discourse with Paul Ramsey’s Patient as Person in 1970. Initially, “personhood” was protective—seeking to stem research abuses against vulnerable populations (children with mental illnesses, African-Americans), to counter medical paternalism, and to resist the ‘‘depersonalization’’ of modern medicine. From Nuremburg through Paul Ramsey to the Belmont Report, the term “person” was invoked to ensure that autonomous persons were given the right to informed consent—whether for research or medical care—and non-autonomous persons (or “all who share human genetic heritage” in the language of the National Commission’s 1975 Report and Recommendations: Research on the Fetus) were protected, even to the point of excluding them from research that could potentially benefit others.

From Personhood to Homo Economicus

But in 1979, almost before the ink is dry on the Belmont Report, respect for persons transmutes in Beauchamp and Childress’ first edition of Principles of Biomedical Ethics into respect for autonomy. Henceforth, talk of persons becomes largely “permissive”—we now have to determine who counts as a person before we can determine what, if any, responsibilities we owe them. Knowing who counts as a person helps resolve dilemmas around abortion, end of life, organ transplantation, stem cell research, etc. Most interestingly, “persons” for bioethics come to be defined as autonomous subjects who express their agency through the rational act of choosing whichever ends further “their own good,” maximizing their own self-interest. Social determinants of health, social location, social structures, even family members rarely enter this calculus. The “person” of bioethics post-Beauchamp and Childress, post-1980, is homo economicus.

In the gene-editing podcast, Aline Kaliban asked “what is it, exactly, that ethicists bring to the table?” While often the dignity or sanctity of persons is held up as a hedge against the endless encroachment of market forces in medicine, the attitude Pope Francis so aptly names as “the throw-away culture,” it may well be that the principles of bioethics subtly serve not as a corrective but rather as a tool of the market.[5] Lisa Cahill depicts science, economics, theology, and liberal democratic political discourse as “thick worldviews” that compete in our engagement around bioethics and health policy. But it’s not an equal playing field. History suggests that the thick worldview of the neoliberal paradigm underlies them all. It shapes bioethics, medicine, scientific research, and medical technologies. This is why it’s often hard to see what bioethics brings.

Clarifying the neoliberal structure of bioethics and emerging medical technologies not only helps us understand the contours of the CRISPR landscape. It illuminates other disquieting dynamics. For example, certain technologies, once approved, become cast as morally normative. If one could eliminate a defective gene from your children using CRISPR, is one not morally obliged to do so? Belying the rhetoric of individual liberty, as neoliberalism evolves in the late 20thcentury, homo economics becomes subservient to that sovereign master: the economic dogma of rational, utility-maximizing self-interest. In a troubling inversion, what must be free now is not persons but the market.

Or why is it so difficult to advance the notion of the common good? Perhaps the answer lies in one of the first steps in the creation of modern capitalism, that original act of privatization, the literal enclosure of the commons in England from the 16th century forward. Step-by-step, material “commons”—even our genomes—are no longer shared. They are patented, commodified (23andMe!), and used as raw materials to create new products for profit and consumption.

If this is the case—if biotechnologies and bioethics and bioethics’ concept of the person are intrinsically shaped by neoliberalism—where are we left with a technology like CRISPR? Such an angle doesn’t yield a simple thumbs-up, thumbs-down, or “we must stringently regulate this new and powerful technology.” Perhaps He Jiankui is not so “rogue” after all. Rather, perhaps the CRISPR babies provide a road-to-Damascus jolt to make us analyze not only a particular technological innovation but the way the infrastructure of bioethics may have enabled it. Let me point to three avenues forward.

Towards a Systems Analysis

First, it is time to begin to make these economic dynamics of biotechnology and bioethical issues visible. The Catholic social tradition is one of the main voices that has begun to do so. Beginning with the liberation theologians in the 1970s, through John Paul II who named the structures of sin of money, power, and idolatry especially in relation to globalizing technologies, to Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ (following Benedict XVI’s Caritas in Veritate), Catholic social thought critiques the practices and effects of neoliberalism—particularly commodification, consumerism, and the exacerbation of economic inequality.

This lens needs to be brought to bear on bioethics. Few Catholic bioethicists have yet done so. These two “doctrinal” areas have too-long been siloed.[6] A social lens asks about the historical and social contexts of concepts. Why did a particular concept arise when it did? Whose interests did it serve? It uses not only the tools of theology and philosophy, but also carefully attends to history and the social sciences. It presses for analyses that are, in the words of Paul Farmer, “historically deep and geographically broad.” One central tool of this “social-analytic mediation” (as liberation theologians call it) is economics, particularly political economy. My colleague Michael McCarthy and I have begun to address this gap in our recent book Catholic Bioethics and Social Justice: The Praxis of US Healthcare in a Globalized World. Catholic social thought here joins an emerging cadre of secular thinkers.[7] But much more work needs to be done.

Second, we need to move away from “single-issue” analyses that have long shaped bioethics (“Is CRISPR ethical or not?”) to broader systemic analyses. What are the connections between the CRISPR babies in China, the new career path of the “professional guinea pig”[8] in the US, the skyrocketing numbers of human research subjects globally,[9] and the serious toll that neoliberal economics has taken on health outcomes around the world by decimating social programs and local economies, just to name a few? (Rogers-Vaughn, for example, sees neoliberalism as causally responsible for an increase in mental health issues). The list could go on.

These issues are all of a piece, pointing to ways in which human bodies become the raw material for profit-making (or cost-savings), a reality woven into the fabric of bioethics and biotech itself. Coming to see this requires, as Pope Francis notes in Laudato Si’, not only hard intellectual work but also moral and spiritual conversion. Can bioethics be converted? Religious traditions—with their vision of thickly connected persons who develop and flourish integrally in communities—could well provide the lever to begin to shape a bioethics that privileges persons over profits. This would move away from a bioethics dominated by the methodological individualism of autonomy and enamored of the methodological individualism of technologies. It would provide a starting point for a radical conversion of our hyper-individualistic and extractive economic philosophy that inflicts austerity on the poor while licensing the almost unbridled creation of biotech products for consumption by the wealthy few.

But it is not only bioethics that needs to be converted. Conversion calls us to a new way of living. Might we declaim against the neoliberal splinter in the eye of He Jiankui while remaining happily blinded by the log of contemporary economics in every other aspect of our own lives? The lens we turn on him, we must also turn on ourselves. As this conversation among Contending Modernities unfolds, it seems an opportune time to reflect on how not only religious convictions (i.e., about persons) but embodied religious practices, such as silence, simplicity, fasting, almsgiving, prayer, the Eucharist, offer the potential for unshackling us from the subtle but pervasive ways that neoliberalism shapes our lives. Perhaps here is the starting point for beginning to come to see the underlying engine driving ourselves, our culture, our bioethics, and biotechnology, and to thereby begin to unhand these interventions and very selves from neoliberalism’s invisible grip.

[1] Contending Modernities,“Science and the Human Person Podcasts.”

[2] This definition draws on Daniel Stedman Jones, Masters of the Universe, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

[3] Bruce Rogers-Vaughn, “Blessed Are Those Who Mourn: Depression as Political Resistance,” Pastoral Psychology 63, no. 4 (August 1, 2014): 503–22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-013-0576-y.

[4] Joseph J. Kotva and M. Therese Lysaught, On Moral Medicine, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans: 2012).

[5] Charles Camosy, Resisting Throwaway Culture, (New City Press, 2019).

[6] Maura Ryan, “Bridging Bioethics and Social Ethics,” Contending Modernities, September 27, 2013,

[7] Global Pharmaceuticals: Ethics, Markets, Practices, eds. Adriana Petryna et al., (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006).

[8] Carl Elliot, White Coat, Black Hat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine, (Beacon Press, 2011).

[9] M. Therese Lysaught, “Docile Bodies: Transnational Research Ethics as Biopolitics,” The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 34 no. 4 (2009).

In 2012, I spoke with Seema, an extremely frail but affluent accountant and young mother who suffered from multiple ailments that had permanently damaged her kidneys. Doctors and relatives had failed to persuade her to obtain a healthy organ from a living donor. She wouldn’t allow herself to pay someone “selling a kidney out of desperation,” when only she knew what it was worth—“more than anything anyone could pay for.” Even receiving an organ from a brain-dead person was hard to accept. “How can I wait in anticipation of someone’s death so that I can live?” she said. But about a year later, Seema finally agreed to put her name on the IKF’s recipient list. Despair over her declining health and fear of leaving her toddler without a mother had overpowered her previous reservations. She chose to optimize her chances of recovery by receiving a kidney from a living stranger.

In 2012, I spoke with Seema, an extremely frail but affluent accountant and young mother who suffered from multiple ailments that had permanently damaged her kidneys. Doctors and relatives had failed to persuade her to obtain a healthy organ from a living donor. She wouldn’t allow herself to pay someone “selling a kidney out of desperation,” when only she knew what it was worth—“more than anything anyone could pay for.” Even receiving an organ from a brain-dead person was hard to accept. “How can I wait in anticipation of someone’s death so that I can live?” she said. But about a year later, Seema finally agreed to put her name on the IKF’s recipient list. Despair over her declining health and fear of leaving her toddler without a mother had overpowered her previous reservations. She chose to optimize her chances of recovery by receiving a kidney from a living stranger.