Contending Modernities Introduction:

Weeks before Civil Rights icon Angela Davis was to be honored for her unflagging commitment to human rights, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) rescinded the February 2019 award, due to concerns that Davis’ support of the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS) movement had been challenged as “anti-Semitic.” In the struggle against modern day racism and oppression, solidarity for Palestinians had yet again been set aside—by a Civil Rights institute no less—as the “exception”: a site of injustice that only one identity group—Jews—might legitimately mobilize for or even discuss, and even then under great stigma. In the past few days, Davis has since been reconfirmed for the award by BCRI, and Michelle Alexander’s “Time to break the silence on Palestine” editorial has placed the issue squarely in the public eye—for the moment.

A year ago, on April 9th-11th, 2018, students from Columbia University and Barnard College held an “Academic Freedom Week” responding to the persecution of progressive academics. Below we share the lecture given on the first day by Columbia University professor and panelist Gil Hochberg on “The Palestinian Exception” (to freedom of speech). In her critique of the forms of censorship performed and enforced by pro- and anti-Zionist Jews and allies, Hochberg identifies the intrinsic narcissism of measuring “real” and “good” Jewish identity with the yardstick of the Palestinian “question.” Discourse and action defining the contours of Palestinian survival become circumscribed to Jews speaking from within Jewish resources about the politics of solidarity—by whom, for whom?—while other identity groups are relegated to a status as secondary allies or excluded from these conversations altogether. As Davis noted, how to navigate these complicated, layered questions of identity, authenticity, and solidarity is a question that strikes at the very heart of the indivisibility of justice.

***

April 9, 2018

Columbia University

1. Anti Semitism/Anti Zionism

News doesn’t last long. A quick flipping through the online news sites of Fox News, CNN, ABC but also the New York Times, LA Times and lesser-known papers today reveals that the latest crazed attack on Gaza has already been forgotten. Hardly even mentioned. News moved elsewhere: to Syria, back to Trump and his kids, back to all sorts of questions and places. There is nothing surprising about this, of course. It takes a lot for Palestine to “enter” the news and it is almost impossible for it to stay there. Part of it is simply “news fatigue“ (how many times can you read or see the same thing, witness the same atrocities when nothing follows in the form of actual political change?). But part of it is of course the strong Israeli lobby and the sad bitter and perhaps inevitable “mix” of the Palestinian question with the longer and stronger (in terms of its impact) Jewish question, translating always to the ghost of anti-Semitism: new or old, real or not.

It is by now become a cliché to argue that a critique of Israel, or of Zionism, is anti-Semitism. I say a cliché because this argument is used time and time and again to silence criticism against the Israeli state, the occupation of Palestine, or Zionism as an ethnic-national principle of separatism that is undemocratic by definition (I remind you of the then Knesset member Ahmad Tibi’s brilliant phrasing: “Israel is Jewish and democratic: it is democratic for the Jews and Jewish for the Arabs”).

It is really a tiring argument that I trust many are tired of debating. Many have combated it before so I do not want to spend the whole time doing so again. Let me say a few words about this twisted logic and then move on to what I believe needs to be part of the next step of our public conversations about censorship and the Palestinian exception.

Anti-Zionism, like Zionism, like any -ISM, can take many forms. It can become or take the form of anti-Semitism, and so can Zionism. But there is absolutely nothing inherent in the critique of Zionism as a principle, or the critique of the state of Israel, that is anti-Semitic. The suggestion that any expression of anti-Zionism is anti-Semitic is an indication of severe paranoia at best, and a manipulated rhetoric at worst. Unless we agree that Jews are by default hated and that anti-Semitism is a mode of collective subconscious; there is no logic to the argument that anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism.

At times this crude logic takes a particularly vulgar turn, making the entire discourse of freedom in Palestine out to be mask for anti-Semitism. This is a perverse argument that suggests that caring for Palestinians and their wellbeing is somehow really about hating Jews and seeking their destruction.

The issue with this zero-sum game (one is either for and against Jews or Palestinians), is not just that it is so limited but that it is further used as an effective silencing machine, time and time again.

Indeed, the so-called ‘new anti-Semitism’ associated with the critique of Israel or Zionism is used by Israeli state officials, the IDF, and many supporters of Israel to explicitly justify state terror and protect Israel from international and domestic condemnation.

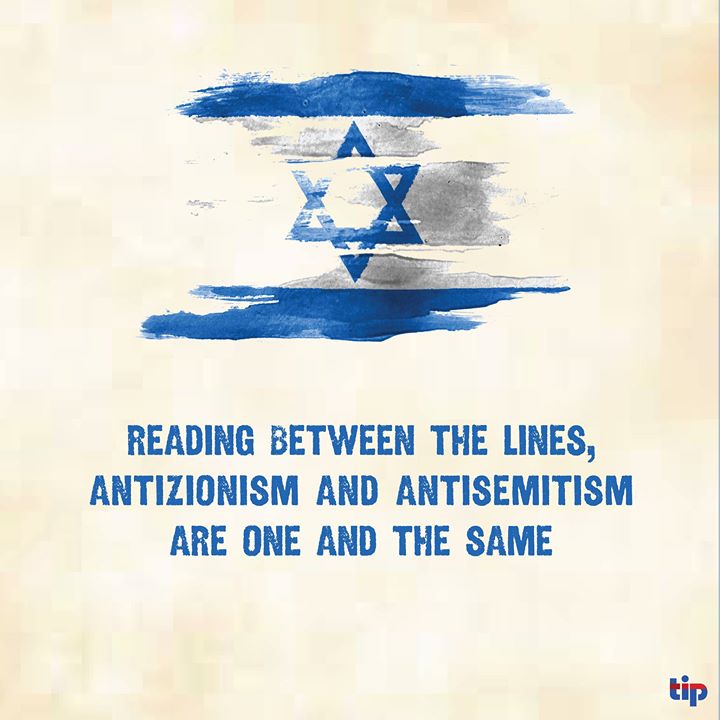

What Israel is fighting, the image at right seems to suggest, is anti-Semitism, represented by the Palestinian flag hugging the swastika. The two are the same. One hugging the other.

This tactic, which aims at silencing critique of occupation, state terror, racism, separatism, and other similar violations, is directed strategically. It aims at Jeremy Corbyn of the British Labor Party, for example, but not at Richard Spencer or Steven Bannon. And it is perhaps most effectively used in attacks against Jewish critics of Israel or Zionism, with the goal, as Judith Butler has noted, not just to silence critique but “to cause pain, to produce shame, to isolate and identify a political position with a personal pathology.”

Jews who criticize Israel or Zionism are thus said to be “self-hating” sell outs, in short: “bad Jews.” And as we shall see, there are bad Jews and good Jews, and real Jews, and all kinds of Jews, all aligned around in different positions vis-à-vis the question of Palestine.

2. Good Jews, Bad Jews

Let me pause for a second and share a bad joke with you. And I warn you in advance of its poor taste. But it is nevertheless quite funny in a dark, bitter way. Or perhaps it is funny because it is in such bad taste, as is often the case with pessimistic jokes. It goes something like this: Why is the Palestinian question really a Jewish question? Because only Jews talk about it, and when they do it is mostly in order to argue among themselves about who is the better Jew.

I introduce this joke which is bitter and funny because it is at once a sad joke about the Palestinian ordeal, which supposedly no one but the Jews care about, and about the Jews who care about Palestine and Palestinians primarily because whatever they say about Palestine determines how they are viewed “as Jews.”

In short the joke captures the irony of history: the inevitable collapse of the Palestinian question into the Jewish question, only that in the 21st century, this historical inseparability, about which Edward Said wrote so thoughtfully, has become somewhat of a farce. Now that the so-called “Jewish question” has no current political urgency, its dominance in framing the question of Palestine has become primarily an anachronistic, narcissistic, and essentialist question about what makes a good Jew.

And here we see how much power the question: “Is Zionism anti-Semitism?” has had at least since the early 2000s. I remind you of Lawrence Summers’ words, published while he was president of no less than Harvard University. Addressing what he saw as dangerous growing anti-Zionist sentiments among intellectuals, he wrote back in 2002:

Profoundly anti-Israel views are increasingly finding support in progressive intellectual communities. Serious and thoughtful people are advocating and taking actions that are anti-Semitic in their effect if not their intent.

Here of course we see the complete collapse between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism. One is the other. Therefore it also means that one cannot be “for the Jews” or “with the Jews” or a “good Jew” if one is anti-Zionist because if one is anti-Zionist one is (in effect or intention) an anti-Semite.

Responding forcefully to the implied accusations, Judith Butler published her defense of anti-Zionism a year later, in 2003. What is important to notice is the manner by which Butler’s response to Summers centered on undoing the tie between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, primarily by undoing the misguided identification of Zionism with Judaism. I quote from Butler:

What do we make of Jews such as myself, who are emotionally invested in the state of Israel, critical of its current form, and call for a radical restructuring of its economic and juridical basis precisely because we are invested in it? It is always possible to say that such Jews have turned against their own Jewishness. But what if one criticizes Israel in the name of one’s Jewishness […] precisely because such criticisms seem ‘best for the Jews’? Why wouldn’t it always be ‘best for the Jews’ to embrace forms of democracy that extend what is ‘best’ to everyone, Jewish or not?

But what does it mean to criticize Israel in the name of one’s Jewishness?

For Butler this means to develop an understanding of Jewishness itself as a non-identitarian project. In her book Parting Ways she writes: “being a Jew implied taking up an ethical relation to the non Jew.” This definition allows her to elaborate a discourse of “Jewish ethics” that is based on Jewish diasporic existence and history as one that ultimately leads to co-existence with non-Jews, and hence as radically different than the Zionist formation of Israel as a “Jewish State.”

The idea of basing one’s critique of the state of Israel on “Jewish sources,” “Jewish ethics” and “Jewish history” is also a tactic and position promoted by Jewish Voice for Peace. Indeed, one of their principles as outlined on their website reads:

We are inspired by Jewish traditions to work for justice and such work is part of our own liberation. We work to build Jewish communities that reflect the understanding that being Jewish and Judaism are not synonymous with Zionism or support for Israel.

I fully appreciate these efforts and think that as responses to accusations of internalized anti-Semitism and self-hatred these are effective strategies. They are also effective in combating the monopoly Zionism claims over Judaism. But this discourse of “Jewish ethics” has its limits as well, and I want to draw attention to these limits, not as a sign of my disagreement with Butler, JVP or others, as much as an expression of my sense that we must become more carefully attuned to how discourses on the left also function as censorship. These discourses also limit what we can say, how we can say it, and who can say what—for Jews and non-Jews—when we talk about Palestine.

Now, let’s face it. I am speaking partially, not only, but partially, as a Jew. Perhaps I am even here as a kosher guard (always good to invite a Jew when discussing Zionism, anti-Semitism, and Palestine). I by no means am implying that the organizers of the event had such intentions in mind. But I also don’t want to ignore this position from which I am speaking which is a position that comes with specific expectations, privileges, and limitations when it comes to speaking about Palestine.

I cannot but speak from this position, which is already over-determined in this context, but I try, very hard, to also speak across it. Because I come to the question of Palestine, to the question of our ability or inability to speak about Palestine, not just in relation to the censorship imposed on us by the right and by academic institutions, but also by the censorship imposed, directly or less so, by the left. When it comes to the question of Palestine, to the question of speaking about Palestine, or the question of who is allowed to speak about Palestine and how, the left has generated some clear frameworks of policed discourse that I find almost as problematic as the attempts to shut down the discussion about Palestine altogether by the right. One such frame is the one I call the “good Jew, bad Jew” framework. It sets the expectation for Jews to speak as Jews and mobilize “Jewish ethics,” thus inevitably turning the question of Palestine into a Jewish question and a question which is ultimately about Jews.

Of course the need to distinguish Zionism from Judaism, in light of Israel’s speaking in the name of the Jews, and as a Jewish state, is very important. But that work, I believe, is now mostly done. I am also quite wary of the language of authenticity (“real,” “true,” “authentic”) because it ends up functioning as yet another wall of censorship and identity regulations, once again in the name of “what makes a real Jew”—an essentializing discourse that renders one’s political views about the state of Israel and the occupation of Palestine in exclusively Jewish terms.

The question I generate for us (for some of “us”) today is: Do we want to go on playing the “good Jew, bad Jew” game? Do we need to play the “good Jew, bad Jew” game when we simply want to voice our resistance to state terror, military occupation, and racial segregation?

I end here, leaving you with the words of Mahmoud Darwish. Not with a poem, but with words he shared in an interview held in Amman back in 1996 with the Israeli literary critic and poet, Helit Yeshurun. At the time he was waiting for his permit to return home to Palestine:

Do you know why we, the Palestinians, are famous? Because you are our enemy. Interest in the Palestine problem comes by way of interest in the Jewish problem. . . If our war had been with Pakistan, no one would have heard of me. So we are unlucky that our enemy is Israel, which has so many sympathizers in the world, and we are lucky that Israel is our enemy, because Jews are the center of the world. You have given us defeat, weakness, and publicity.

These words are provocative. They are meant to be. And to take them seriously, I think, is to begin to reconsider and rethink the idea of what it means to be speaking “as a Jew” or from a “Jewish position” or about “Jewish ethics” when speaking or trying to speak about Palestine. Can a Jew speak about Palestine, about the atrocities that take place in Palestine, not as a Jew? Can she speak in the name of solidarity, not in the name of authentic Jewishness or Jewish ethics? Can the question of Palestine ever become something that isn’t already and essentially a Jewish question?