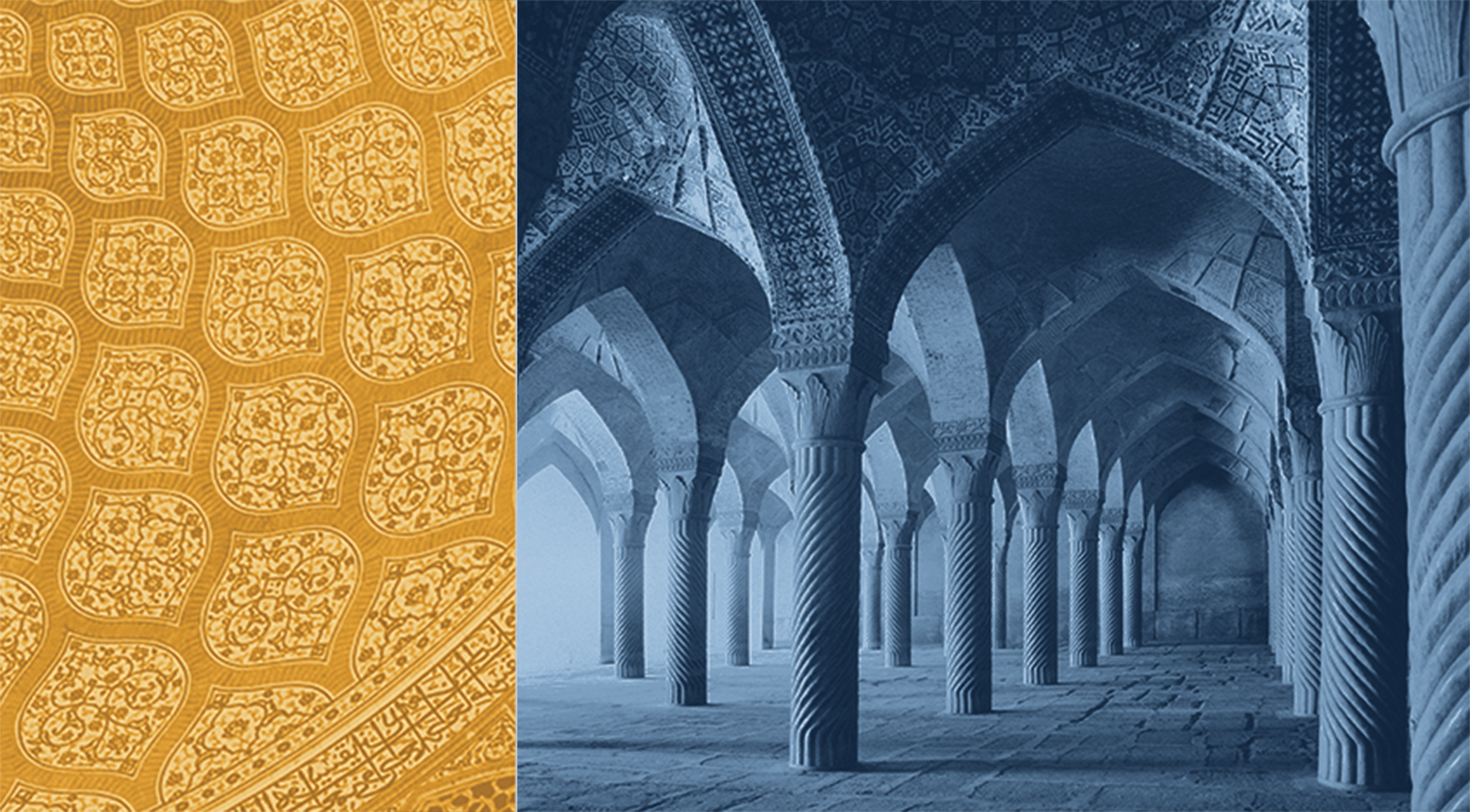

Islamic tradition portrays jinn as mysterious shapeshifters who can morph into different forms, usually invisible to the human eye. Constantly in motion, they are elusive, evading human capture. Like the mysterious jinn, knowledge possesses an uncanny ability to transform into something new and unexpected. As time passes and I look back at my study of Muslim difference, it takes on a new shape, barely recognizable from the form it first took when it entered my view two decades ago. More than an inert object of study, Muslim difference reminds me of its own agency, its capacity to evade definition despite my futile attempts to set limits and boundaries upon it. The brilliant contributions to this book symposium remind me that once any piece of scholarship enters the world it is transformed by those who read, engage, critique, and refashion it in new contexts—discursive, social, and historical. The responses take us on a thrilling tour across the heterotopic spaces of the madrasa, Sufi lodge, hospital, and clinic, revealing the varieties of Muslim difference, past and present.

Between Muslims

Although The Muslim Difference draws attention to the fragile line distinguishing Muslims from non-Muslims, all respondents, to some degree, reflect on the lines dividing Muslims from other Muslims. Martin Nguyen asks, “What can we say about the differences that divide our Muslim communities or those that divide our own selves?” Concerning the physical, psychic, and spiritual landscape of ‘afiya, Ashwak Hauter explores “how different traditions of Islam are expressed and negotiated between my interlocutors.” Anna Bigelow considers how adepts in the medieval Suhrawardi Sufi community grow spiritually through their social encounters with one another. Haroon Sidat reflects on how his postgraduate training in the secular academy transforms his relationship to the Muslim scholars and students at the British Deobandi madrasa in which he first studied Islam traditionally.

The respondents’ turn toward inter-Muslim difference is not as strange as it may first seem. In my book, I advocate for conceiving of Muslim difference not as a binary opposition to non-Muslims but as a continuum that also cuts across heterogeneous groups of Muslims—Sunnis and Shiʿis, men and women, Arabs and non-Arabs, free persons and slaves, young and old, human and jinn. By framing Muslim interreligious relations within a wider field of social and political associations beyond religious identity, we come to see that Muslims are not cut from the same cloth—that Muslim identity is relational and intersectional. All the responses, through their unique interpretive lenses, highlight the diversity and heterogeneity of Muslim lifeworlds.

The Gog and Magog Outside and Inside Us

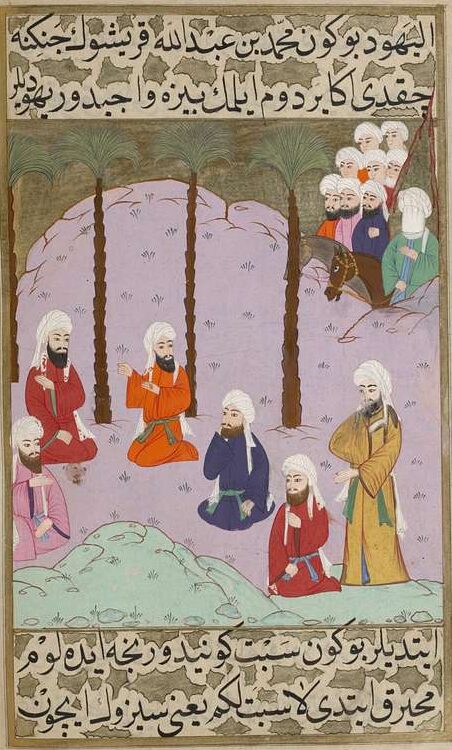

The Qur’an (18:94) describes the monstrous figures of Gog and Magog as “spreaders of corruption on earth (mufsidun fi’l-ard).” They are so disruptive and dangerous that a mysterious hero, dubbed as Dhu’l-Qarnayn, “The Two-horned One,” builds a wall to divide Gog and Magog from humankind. But the Qur’an warns that this wall will one day fall. In the End Times, Gog and Magog will finally break through the wall and overwhelm their helpless victims, like water breaking through a dam and engulfing all who come in its way (Qur’an 21:96). The Bible likewise speaks of Gog and Magog in apocalyptic terms. Although it makes no mention of a wall, Revelations 20:7–10 warns that Gog and Magog will wreak havoc in the End Days, joining Satan in a final battle against humankind.

Drawing on a seventh-century apocalyptic composed in Syriac, Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, both Muslim and Christian exegetes came to identify the figure who built the wall as Alexander the Great. Medieval mapmakers, Christian and Muslim, portrayed the foreign land where Gog and Magog resided as an actual physical place; it was a land of unbelief, danger and chaos, a place to be feared. Blurring the line between fantasy and reality, Christians and Muslims across time and place imagined a host of dangerous Others as monstrous embodiments of Gog and Magog: Christians saw Gog and Magog as Romans, Goths, Scythians, Sarmatians, Huns, and Mongols; Muslims saw them as Turks, Vikings, Portuguese, and the Dutch. As harbingers of danger and disorder, Gog and Magog helped materialize the boundary between self and other.

But Gog and Magog not only represent our deepest fears of the monsters that reside outside us; they also represent the monsters that reside inside us. Both Hauter and Nguyen provoke us to confront the alterity not merely outside us but within us. Nguyen asks, “What is disclosed when we seek to understand the fine line of difference within us all? What separates that which makes us human from that which makes us otherwise?” Nguyen explores these existential questions through a profound theological meditation on the “darker side of difference” that revisits human history’s first murder: the Biblical/Qur’anic story of Cain and Abel, which bears witness to the unleashing of Cain’s monstrous inhumanity. In Nguyen’s psychospiritual reading, “Cain represents an inner impulse focused solely upon the self—a self (nafs), the Qur’an warns elsewhere, that commands to evil” (Qur’an 12:53). Cain, in other words, lets loose the monster within, resulting in “violence-unto-death, the inhuman.” Abel, by contrast, retains his humanity. This polarity between human and inhuman, avers Nguyen, resides within us all. As I argue in my book, we are all difference-makers, drawing lines between who we are and who we are not. But we cannot allow these differences to transmutate into subjugation, violence, terror—lest we become monsters ourselves.

Hauter likewise exposes the alterity within. She turns away from the dark side, however, toward the potential light within. Drawing on her fieldwork on individual and collective ‘afiya in hospitals and clinics, she sees a believer’s focus on the nafs not as innately nefarious, but as potentially generative. The nafs, “self/soul,” is not static, but dynamic, oscillating. “The unknowability and oscillation of the soul imbues individuals with a radical otherness or alterity.” Far from being an exercise in monstrous self-absorption, Hauter sees “vitality and potentiality” in a person’s daily repertoire of ordinary practices that disclose how the self relates to the soul. “In the gap between self and soul and self and other,” she argues, “there is a field of possible exchange, recognition, and innovation.” In this way, difference, whether small or great, is not exclusively a pathway to subjugation of the other.

We are all difference-makers, drawing lines between who we are and who we are not. But we cannot allow these differences to transmutate into subjugation, violence, terror—lest we become monsters ourselves.

Both Hauter and Nguyen make compelling arguments. Both suggest, in different ways, that difference need not deteriorate into domination. How people attend to their nafs, and subjugate it to themselves, determines whether difference in its myriad forms will become a means to subjugate others. Those whose nafs overwhelms and consumes them, as it did Cain, may seek to dominate others. But those who vigilantly watch over and overwhelm the nafs until it is broken, as the Sunni theologian Ghazali urged, have no need to claim victory over others—for they have triumphed over themselves (Qur’an 23:1).

Technologies of Self-Cultivation

While Nguyen and Hauter draw attention to the possibilities and consequences of cultivating particular kinds of subjectivities, Bigelow and Sidat illustrate the essential but oft-neglected role of imitation in that process. Indeed, my book can be read as an extended commentary on the Prophet’s pithy but potent dictum, “Whoever imitates a people becomes one of them.” Whether read by Muslim thinkers as an admonition or encouraging homily, the hadith advances a universal truth about human becoming and belonging: people become who they are based on whom they emulate—and whom they don’t.

Anna Bigelow’s nostalgic, empathetic, and insightful reflection on the spiritual and social dynamics of emulation in the Suhrawardi Sufi community reminds us that people can learn from imperfection; people learn from their mistakes—and from the mistakes of others. Sufi adepts learn how to be better Sufis through their encounters with boorish Sufi novices who lack self-discipline and social etiquette (adab). They learn how not to be. When Sufi adepts shun emulating the uncouth behaviors they witness in others, they not only distinguish themselves from them, they also spiritually grow The unexpected self-cultivation Sufi adepts gain from these social encounters transforms these boorish neophytes whom they look down upon into their teachers worthy of reverence and love. After all, these novices help them progress on the spiritual path and realize the fullness of their human potential. In this sense, all social encounters are teaching moments that lead to the Sufi adept’s spiritual transformation.

Between Academia and Alimiyya

Sidat also underscores the power of imitation to shape Muslim being, becoming, and belonging. He wonders if his liminal position in the barzakh between academia and alimiyya can become a productive space that bridges different epistemes and builds new ones. Alimiyya refers to the curriculum of the traditional madrasa that produces ulama (sing. alim), religious scholars who become custodians of the Islamic discursive tradition. This is not purely an intellectual role. They are expected to live what they learn, embodying what they know in their everyday conduct. As a result, they become spiritual exemplars, communal leaders who inspire ordinary believers to become better. Sidat refers to this socio-spiritual role of the Muslim religious scholar as imitatio imam (imitation of the imam). These scholars model Prophetic behavior, Sidat tells us, by being imitators of the malakut, the angelic or imaginal realm that cannot be apprehended by the physical eye. Imitation thus becomes a chain linking ordinary believers to scholars and scholars to angels across the realms of the visible (mulk) and invisible (malakut). Imitation, in other words, leads to collective solidarity across the cosmos.

Muslims, Mimesis, Modernity

In response to the encounter with colonial modernity, Muslim thinkers across the Muslim world—South and Southeast Asia, North and West Africa, the Levant, Arabia, and Europe—composed Islamic treatises warning ordinary believers against becoming Muslim mimics estranged from their tradition and themselves. While neither uniform nor universal in content, the global spread of these discourses during the 18th–20thcenturies speaks to the collective trauma experienced by Muslims under colonial rule.

Imitation thus becomes a chain linking ordinary believers to scholars and scholars to angels across the realms of the visible (mulk) and invisible (malakut). Imitation, in other words, leads to collective solidarity across the cosmos.

Many of these treatises were borne of violent political upheaval, from the Spanish-Moroccan War and civil strife in Nigeria to the British colonization of India and the creation of a secular republic in Turkey. Iskilipli Aṭĭf Hoca (d. 1926), was executed by the newly formed Turkish Republic for composing a treatise forbidding European style hats on the pretext that it undermined a state law banning the tarbush. In this new social imaginary, to reject a European way of life was to reject civilization itself.

Although built on a premodern Islamic discursive tradition, the shape of these modern Islamic discourses against imitation were different; they displayed Muslim anxieties over aping the west in everything from wearing brimmed hats and bowties to celebrating Valentine’s Day and Christmas. The Prophet’s mantra against imitation transformed into a slogan of anti-colonial and anti-western resistance. In fact, Muslim adoration of all things European became so pervasive that Iranian intellectual, Jalal Al-e Ahmad (d. 1969), dubbed it a plague, gharbzadegi, translated variously from Persian as Westoxification or Occidentosis.

Nevertheless, it was, and is, an Islamic discourse that assumed a religiously plural public space where Muslim encounters with Christians, Jews, Hindus, Zoroastrians, and others were possible. It is propelled by the conviction that social encounters with Others are potentially transformative, that mimesis, conscious and unconscious, is normal but dangerous.

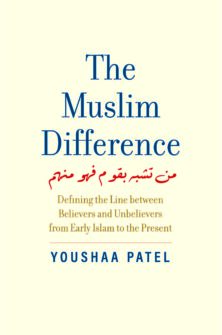

So what does the present and future of Muslim mimesis look like? Well, one thing is for certain: it won’t look the same everywhere. In the epilogue of my book, I offer a preliminary sketch of how to reread the Prophet’s dictum on imitation beyond confessional lines—as an exhortation to emulate what is best in others regardless of belief and to be mindful of the divine breath that inheres in all humans. To be clear, this reading is an attempt to expand the contours of Muslim difference, not to erase it. Whether or not my audience finds my rereading of tradition persuasive, I hope that the genealogy of Muslim difference presented in my book will help scholars and laypeople think more clearly and critically about a politically loaded, misunderstood, and poorly theorized subject.

The shape and style of Muslim difference continues to matter. Today, it is common to hear peacemakers and politicians make anodyne public appeals to “overcome our differences.” That is, they portray difference as an obstacle to solidarity—that conflict, even violence, is the inevitable outcome of difference. But if we listen to Muslim thinkers across time and place, as I urge readers of my book to do, we learn that being different can be a very good thing. Today, a call to Muslim difference is not a call to reject modernity or to reject the west. It is not a call to despise the Other. It is, I believe, a call for Muslims to shape and style their own modernity, a modernity that is almost the same but not quite.

In

In