Background Introduction

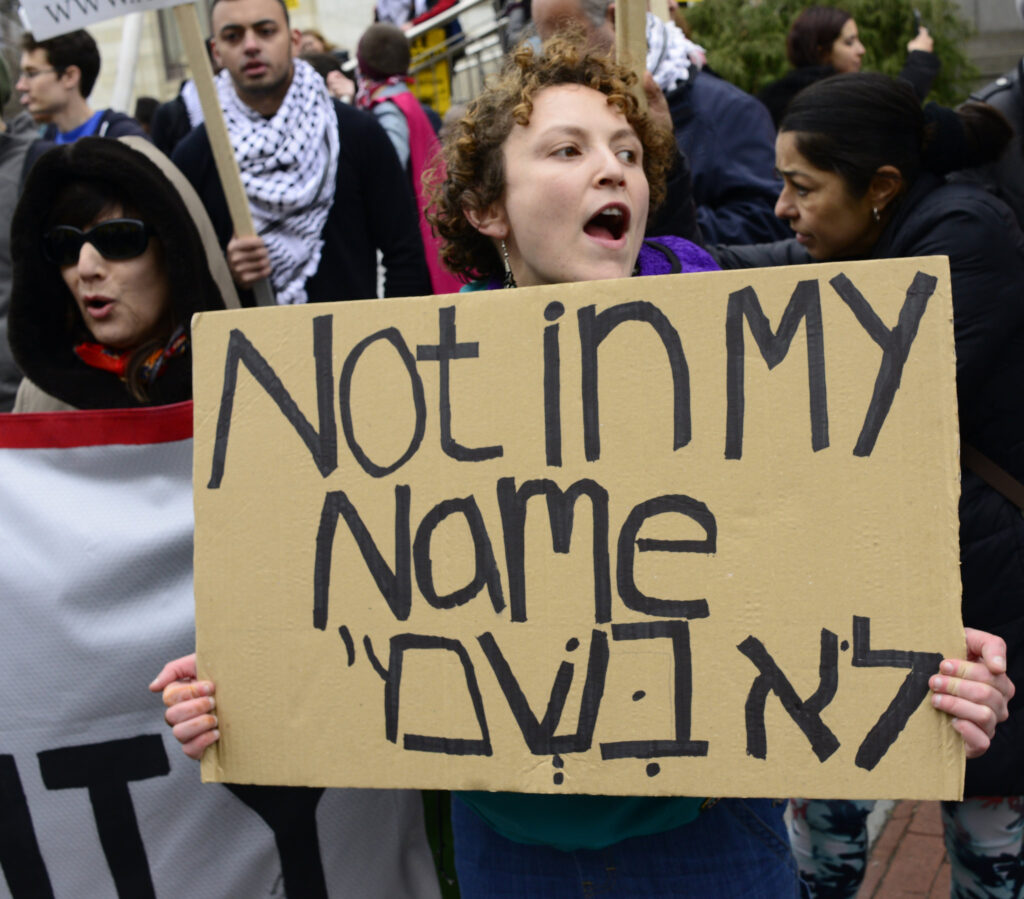

Amidst the genocidal onslaught on Gaza over nearly the past year, universities have pondered whether, and how, to respond. From student protests calling for boycott and divestment, to faculty organizing, to administrative repression, universities around the world have been a site of contention and debate.

What should the role of the university be in the face of genocide? What does the university’s mission demand? And what responsibilities do university leaders have in the current climate?

These questions could be addressed to any university, but in the letter that follows, they are addressed to an Israeli university, particularly to Tel Aviv University, to its president, Professor Ariel Porat, from one of its Palestinian faculty,[1]Professor of anthropology Khaled Furani.

This letter is part of a conversation following the arrest and release of Palestinian Hebrew University Professor Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian. On April 30, 2024, seventy-three current and former Palestinian academics at Israeli institutions of higher education sent a letter to the Association of University Heads in Israel (VERA). This body is comprised of the presidents of nine universities, including Ariel University in the occupied West Bank.

That letter holds the universities collectively accountable for the campus atmosphere of repression and retribution that contributed to their colleague’s arrest. It asks VERA to issue a statement demanding that charges be dropped against Professor Shalhoub-Kevorkian and to uphold her safety, academic freedom, and right to free speech. Only days earlier, VERA had issued a public statement expressing concern with “Violent Demonstrations and Anti-Semitism on US Campuses.”

In their letter, the Palestinian academics include as an action generating a lack of safety the referencing of ‘Amalek, a biblical people that the Israelites are enjoined to decimate, referring, in part, to this language appearing in a speech given by Porat at Tel Aviv University (TAU) on November 7, 2023. The International Court of Justice has cited such language as incitement to genocide.

VERA did not issue a public statement in response to the academics’ letter. Porat’s response amounted to directly writing to seven faculty at his institution who had signed the letter. In his letter, Porat defends his reference to ‘Amalek and his record of upholding academic freedom, inviting the faculty to contact him directly should they ever feel unsafe.

Despite spending the academic year in Germany, Furani felt threatened at a distance, personally, for his Palestinian academic community, and for his family members in Gaza. He spent many months thinking about how to express this lack of safety to Professor Porat and about how to ask that he, in his role as a university president, lead toward safety and dignity for all in the land. Upon his safe return home from his sabbatical, Professor Furani sent the following letter to Professor Porat. Footnotes have been added to the original for clarification.

The Letter

August 31, 2024

Dear Ariel (if I may),

There is a prophetic tradition (hadith), far away from modern liberalism and close to the ethical precepts of ancient Judaism, whereby the Prophet Muhammad reminds us that the best of striving (jihad) is speaking with justice (haq) before an unjust authority (sultan ja’ir). In this letter I strive to speak just so, about what you are owed, including my understanding of what you yourself owe. I pray that truth (haqiqa) remains my companion in every word. Please forgive me if I inadvertently deviate from it and please strive to listen deeply when you hear it.

Ultimately, I write this letter to beseech you to be more conscious and attentive toward leadership, so that you may remember truth and make decisions founded upon it, rather than unthinkingly follow decisions made for you. Nothing less than this task is necessary for leading. And in our diluvian times, leading, genuine leading, is required if we are to emerge from the flood. You, indeed all of us, must decide where we stand in this blood-drenched land in need of recovery of justice, freedom, and equality for all lives between, and beyond, the River and the Sea.

I owe you an appreciation, an apology, and this very letter. Appreciation, because to this day, I carry with me the ethically profound human touch of your personal call on a Saturday morning over three years ago to make sure that my family and I were safe in our neighborhood as throngs of Jewish thugs (with “the tolerance” of state security) threatened Palestinian Haifa.[2]

I also appreciate the ways in which you stand out among your peers in seeking to ensure your faculty’s personal safety, and also to protect certain civil liberties, responsibilities which other university presidents seem all too willing to abdicate. As you commit to these types of freedom, you also stand out in your manifest desire to listen. It is your desire to listen that made it possible for me to write this letter. It reverberated all the way over to my sabbatical abroad. My physical distance undoubtedly hindered my ability to follow and fully appreciate what you have been doing day by day to safeguard these types of freedom.

I owe you an apology for writing this letter in English, a language that is native to neither of us. For reasons that lie with you, Arabic is not an option. For reasons that lie with me, neither is Hebrew. Although I am working on recovering my relation to a native Hebrew, whose no fault it is that modern Zionism colonized it, at this moment I must, the world being what it is, resort to the foreign, and yes colonial, language of this letter, so that words may flow from my heart to yours.

I now turn to what you owe as a university leader. You owe us, Palestinian faculty and the wider Palestinian community to which we belong, and also and essentially yourself, a more genuine sense of, and a truer commitment to, safety (aman). I am referring to a safety native to the land, enduring and encompassing all peoples, neither false nor prejudicial. You have kindly and keenly asked us to contact you should we ever feel endangered. I am doing this now. Shocking as it may seem, my need for safety also stems from a danger present at times in your words as well as in your silence, in your actions and in your non-actions.

Your resort to the annihilationist language of ‘Amalek, however analogical your intention, constitutes danger. Your recruitment of funds for students drafted for reserve service in an army whose leaders are charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity constitutes danger. Your mustering of campus resources for ideological, surveillance, strategic, and other forms of support in service of slaughter in Gaza masquerading as self-defense constitute danger.

Your utter silence on the destruction of higher education in Gaza presents danger. Your failure to institute on campus a deep introspection that examines how we arrived at the calamity befalling the land, the peoples on it and beyond it—and not merely since last October, nor since the last couple of years or decades, but for at least the past century—also constitutes danger.

Your vocal challenge of attacks on democracy while remaining utterly silent on this democracy’s attacks on human life, including its brutal occupation of a people, presents danger.[3] Questioning the legitimacy of the current government, while keeping unquestionable your nation-state’s foundational violence—endemic to any colonial state—presents danger. This danger amounts to the tragic hindrance of your ability to hear and to see the ways in which you are made to help perpetuate a certain violence even as you earnestly combat another.

You might begin recognizing this disparity by listening to your very language. As you seek to protect “democracy” and its “rule of law” you participate in normalizing this law’s violence. You normalize this violence when sounding like the state. Like it you call the current iteration of a vast tragedy “war.” In this so-called “war,” you seem to attribute “murder” and “terror” exclusively to “the other side,” but never to your state. Who commits “illegal violence” and what “legal violence” and even “law” amount to seem set and set beyond the frame of questioning.

Both the substance and the agent of terror are made to appear self-evident, rather than merited subjects of critical learning, our foundational task at the university. The task of learning that engenders clarity of thinking becomes more, not less, vital for the university’s integrity when that university depends on a state. Indeed, it is fateful when, out of a history of colonialism, that state seeks to numb, confuse, and normalize its occupying powers, and malign any and every form of resistance to those powers, even the most non-violent, as “terror.”

Allowing state violence to hide in what counts as “normal” or “legal” undermines your very striving for my safety. Worse still, your sense of “safety” itself becomes a form of endangerment every time it turns blind to, and tunes out, state violence. No humanitarian impulse can remain safe under the inhuman and dehumanizing power of the modern state. Treated as self-evidently “legal,” this state violence is bound to turn reality lethal for all, for citizens from this or that “sector” and for non-citizens alike.

Ultimately, when you fear violence that is against “the law” yet normalize the violence of “the law,” my safety is not the only casualty. Yours is too. The danger to safety here lies not in some abstract inconsistency but in a real ethical one. It is a safety in which you can properly hear, see, and sense our common world. If you stand outside the safety of an ethical landscape, then neither us nor your leadership nor the university you are charged with leading can be assumed to be safe.

Where do you and your leadership stand, within or outside of an ethical landscape? Do you lead from moral agency or are you pursuing a hollow non-leadership, or something in between? Sadly, instead of seeing you lead, I see you as being led. Instead of “making history” by “stepping outside” of it, you appear to surrender to its vagaries. Should you dare to examine and self-examine what may appear self-evident and to question, as a steady form of knowing, what may appear scary, then we can be assured that you are leading. When you dare to take steps, not merely ahead of your homologues but wherever necessary, even stand alone, then we know that you are leading.

Ultimately, when you fear violence that is against “the law” yet normalize the violence of “the law,” my safety is not the only casualty. Yours is too.

The “aloneness” of genuine leadership requires you to find a place outside the matrix dominating your society, that is, outside of Zionism. When you remember what Zionism wants you to forget, that this land was never empty and that all peoples on it from the River to the Sea, are all equally deserving of life and of mourning over it when lost, then we know that you are leading. When you transcend the glitter of sanctioned words and venture toward justice for all, then we know that you are leading. When you recognize that the dangers derived from “coordinating” (Gleichschaltung)[4] with and for the state exceed those threatened when questioning its hubris, then we know that you are leading.

Rather than seeking to end the historic confusion of Jewish safety with Jewish supremacy and the conflation of Jewish freedom, or any freedom, with sovereignty, you have helped perpetuate a fatal confusion. This fatal confusion has brought a European poison to Palestine, at times to combat European toxins and at other times to spread them, while masquerading as a theriac.

This European poison, modelled after, while capitulating to, fateful European nationalism and xenophobia, is modern Zionism. Allured to drink from this supposed theriac and by spreading its drinking, you join thoughtless condemnation of what could bring you and your society back to sobriety, indeed to health and to freedom.

Your leadership has our university go on, in frenzy, fighting against the academic boycott,[5] for example, rather than strive toward understanding, which is distinct from justifying, its motivations and aspirations. While wanting to be democratic, your leadership treats the non-violent boycott movement as demonic. Why not instead leaderly encourage what thinking—because it is thinking, all the more so at an institution entrusted with it—requires on this matter as on any other: to think it through and debate it?

Often, we, Palestinians, have been asked about where or who our Mandela might be. Despite this question’s many flaws, it has value in that it can easily be turned around. As you seek to lead, please attune your ears, open your eyes, and ask from your heart with due humility and remembrance: from whence and under what conditions could an Israeli Jew emerge as a de Klerk? If and when you are ready to recognize that it is “the drink” itself and not only “the drunkard” (a minister here, or a prime minister there) then genuine leadership could await you.

Do you want to stay on board a chariot of death, recharging it with Zionism, and irrecoverably lead our peoples in this land toward an abyss, or will you summon the courage to steer us away from colossal descent?

Let us recall, when entrusted to lead a university, you are entrusted to safeguard its foundational mission to pursue learning unhindered. Our university, like other universities around the world today, has been entrusted with safeguarding one of the greatest capacities given to humans: to think. Through thinking we learn to perceive truth and discern it from falsehood, along with beautiful from ugly and good from bad, and crucially, acting from failing to act for justice.

This mission is why, when you preside over a university, you are poised to save, or destroy, bodies and souls, of persons as well as of polities. More than merely training our thinking away from perdition in this world, if committed to striving to the ideal of justice for all—not only for some—a university can chart new and previously unknown paths for existence.

In reality, TAU violates this original entrustment, as would any university anytime it participates in a state’s domination of a people. TAU currently, and rightly so, refrains from serving as an obvious arm of the state’s policing, surveillance, or prosecution. Yet it seems quite comfortable, rather eager, to dutifully join its ideological arm, through TAU’s commitment to “hasbara” efforts. Instead of allowing in some light, instead of welcoming new or difficult or “heretical” voices, TAU goes on to participate in your state’s denial of Palestine. This denial is not simply of a past on whose literal ruins TAU exists, namely on al-Sheikh Muwwanis. It has to do with a future that all peoples of this land, no matter the state, could and should enjoy with their progeny and without privileging one people over another.

Your recent conference focusing on the future demonstrates perception of one and only thing: a state.[6] You see a single state and those assimilated by it, but not the multiplicity of peoples, their histories and futures, banished by it. Numbed by the state while imagining its future, TAU holds Palestinians in the realm of suspicion. They are singularly invoked as the object of “security” experts. Just like the state itself, nothing and no one seems higher for you than the state, not its people nor any people.

Instead of allowing in some light, instead of welcoming new or difficult or “heretical” voices, TAU goes on to participate in your state’s denial of Palestine.

Voices for justice, for truth, and for reconciliation are rising up loud and clear from around the world, and even on your own campus, so that we may all, Israelis, Palestinians, and more, re-found our joint existence, outside Zionism’s dominion in this land, yet such voices seem to meet your condemnation. You refuse to hear them. Indeed, you malign them. This denial by someone entrusted with thinking becomes ever more stupefying in the face of the rapid fraying of existence of both peoples, if not of the world entire.

A university that participates in the crushing of another people’s freedom cannot possibly remain a university, for it robs freedom thrice: first from the people its state dominates, second from the people claimed by the state as its own, and third from thinking. Can a university that abnegates its own freedom be called, properly speaking, a university?

Ultimately Ariel, it comes down to whom you want to serve as you lead a university. It has been said that one cannot serve two masters, only one. Strikingly, you seem to be caught in the service of three at once: knowledge, market, and the state. The perception available to your heart is quite likely torn and fragmented in the torrent of attention they each demand from you. Stepping back to perceive the whole, as any leading—including of one’s own existence—requires, must be rather difficult. Under this triple servitude, your perception might be smashed to smithereens as readily as a grain under a grindstone.

You are rightly indignant about a government that you find noxious for a healthy life, a life to which all creation, without exception, is entitled. Yet you have not allowed yourself the possibility that the current government is merely the latest concoction of the state’s steady and stupefying secretion of poisons. This stately poison has kept flowing, no matter the government, no matter the prime minister who came and went. There is nothing that you may say about the current government and its members that cannot justifiably be said about your state for the entirety of its life: paranoid, lying, deceiving, manipulating, thuggish, divisive, corrupt, massively destructive of human bodies and souls, and, of course, perpetuating a denial that numbs the senses necessary to recognize it all.

Only now, the masks and walls designed to obscure this poison are disintegrating, along with the sealed-off cellar that aims to hide its casualties. Somehow and somewhere, you surely know that this cellar has been there all along. It is known to many Israelis as occupation. Anyone alert and daring to peek can see behind its literal walls offering a false safety and freedom and find an abyss. Now the abyss along with its poison is catching up with you and perhaps the whole world as well.

Ariel, you have indeed led in reminding that a time of calamity can also be a time of recovery. But will you, amidst the continuing slaughter, lead with courage, notwithstanding the risk and fear, to a recovery from the dominion of modern Zionism? What needs to be renewed, outside and before this Zionism, is a way of living together in this land that embraces all. And we should be able, inshallah, to re-learn it. Peoples have lived together and found refuge in this land for millennia. For the sake of our children, grandchildren, and the world entire, we cannot allow a single century to undo all those that came before it. We cannot allow a modern Zionist un-learning of this rooted history to deracinate the historical living together in and with the land.

A free university must begin to relearn to belong to this place, rather than this land to “us.” It would see that no one and nothing needs to be hemmed into serrated and clashing identities, as demanded by the state’s false promise of “security.” If it is not too late, certainly before the utter ruination of the university as a beacon of learning, I hope that you realize that only one of the three masters you serve can and must be served at a university. You know which one.

Before too late, please do the reckoning that allows you to perceive that what ultimately the state cares for is its own life, not the lives of its citizens nor of the “world Jewry” it purports to defend, let alone the subjects of its terror in the sealed-off cellar, now exposed for all those who care to see. Before too late, ask yourself in what ways you, as a citizen of the state, have been party to a deal with a Mephisto falsely promising manna.

A free university must begin to relearn to belong to this place, rather than this land to ‘us.’

In the instance of a Jewish state, it means, perhaps above all else, the bartering of a profoundly ethical tradition, committed to justice, the best foundation of any and all governance, for a non-ethical institution (the state), which sells both justice and ethics on the altar of its own life, believing in its inviable perpetuity. What is more, being a modern state, your state has duped you into a false sense of safety and into a fake sense of belonging. It has duped you into a sense of freedom, including freedom from violent death, despite how violent, militarized, and nuclear it has become.

At stake therefore is more than learning at an institution, that is, the university, whose vital mission is to safeguard learning. At stake is our existing and belonging on this land and beyond it. Beware that as they damage learning, the state and the market also damage existing. So please open your eyes and attune your ears and ask with your heart: what have I not been seeing, hearing, and feeling, when my horizon is only the stupefying idol of the state and its stupefying images of riches?

You must have had enormous patience and power if you have made it to these lines in this letter. At the end of this exhortation, let us recall that God commands that we govern with justice, justice for ourselves and for others. To forget this is to forget a crucial message from Amos 5:26–27 who warned against the perils of images we make for ourselves. I pray that you heed his advice for recovering a perception of justice: “You also carried your king, Sikkuth, and your idol, Chiun, the star of your gods, which you made for yourselves, and I will exile you beyond Damascus…” [7]

The land, including its prophets and poets, has taught us an important lesson about the self-deceptive, self-destructive pursuit of seductive power and wealth: Crusaders’ castles have no durability here. What lasts grows in and from the land, like za’atar, sage, and olive trees, and the people who cherish them. If you recover your perception for justice, I trust that you will help open a path for a joint healthy life like that lived by the land’s enduring flora, and not by the transient and deserted castles crumbling in its midst.

Sincerely,

Khaled

Notes

[1] Palestinian faculty at Israeli institutions of higher education all hold Israeli citizenship.

[2] In May 2021, what is commonly known as habbat al-karamah (Arabic for “dignity uprising”) was instigated by heightened Israeli assaults on al-Aqsa Mosque and al-Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in East Jerusalem.

[3] Professor Ariel Porat has been a vocal proponent of the pro-democracy movement challenging attempts at “judicial reform.”

[4] Gleischaltung evokes Hannah Arendt’s critique of German intellectuals for coordinating with the Third Reich. See e.g., Arendt, “What Remains? The Language Remains: A Conversation with Günter Gaus,” in Essays in Understanding, 1930-1954: Formation, Exile, and Totalitarianism, 11.

[5] Professor Porat has called on his faculty to assist in thwarting the academic boycott. Relatedly, on May 21, 2024, VERA issued a statement in response to the Conference of Rectors of Spanish Universities’ decision to join the academic boycott.

[6] Professor Porat convened a conference on June 19, 2024 titled “Israel’s Future.”

[7] The original letter gives the original Hebrew verse. This English translation is based on the New King James version.

This post by Bashir Bashir, co-editor of The Arab and Jewish Questions alongside Leila Farsakh, introduces a symposium on the book by describing the wider research projects that gave rise to it. (

This post by Bashir Bashir, co-editor of The Arab and Jewish Questions alongside Leila Farsakh, introduces a symposium on the book by describing the wider research projects that gave rise to it. (