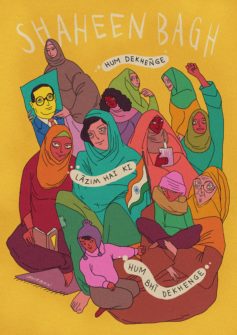

Beginning on December 14, 2019, and lasting until they were forcibly removed when India went into lockdown to address COVID-19 on March 24, 2020, protesters occupied a major road in the neighborhood of Shaheen Bagh in the southern part of Delhi in order to demonstrate against the combined effects of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC)—a 24/7 protest that has lasted over 100 days. Susan Ostermann’s post explains these new laws in greater detail. At the heart of this peaceful protest were women from the middle-class neighborhood itself who were often identified in the press as “housewives.” Many of them were middle-aged or older and many were wearing hijab. Around them sprung up street art, a revolutionary library, children’s activities, and more. The protest inspired solidarity protests around the country. Protesters faced threats from far-right Hindu groups to forcibly clear the area. These threats materialized into actual violence when vigilantes fired guns into crowds of nearby protesters. On social media and in the press, protesters at Shaheen Bagh describe protesting not just against the CAA and NRC (and the Bharatya Janata Party [BJP], the ruling party in government that passed these laws) but on behalf of India’s constitution and the secularism it enshrines, offering an argument about how to define Indian democracy, and who best represents that democracy. They do so by deploying precisely the identity markers that supposedly mark them as oppressed and other: their status as women, female family members, and Muslims.

The Shaheen Bagh protests deploy representations of kinship and home to underscore the vision of a secular, inclusive democracy enshrined in the constitution. Rather than understanding the home as a passive space to which persons retreat from the “real” world, the protesters at Shaheen Bagh demonstrated the enormously generative potential of home and kinship for rewriting democratic values. The Shaheen Bagh protests are innovative not because of the gendered identity of the protesters, but because of how protesters have mobilized that identity to contest powerful scripts of citizenship, religion, family, and nation. Shaheen Bagh’s protesters offer lessons for how to reconceptualize links between public and private, providing new terms for inhabiting domesticity and democracy. Such reconceptualizations are especially valuable as the COVID-19 crisis underscores connections between private labor and public value which are typically hidden from view.

The protesters at Shaheen Bagh address and invert the representations of Islam, gender, and family that the BJP has deployed to defend the CAA and other legislation that many see as Islamophobic. In passing the CAA, India’s ruling party has suggested that some people belong in the Indian nation-state while others do not, depending on religious affiliation. This notion builds on longstanding efforts to portray Muslims in India as outsiders, “invaders,” or, more recently, “guests” of a Hindu nation who ought to follow the norms of their hosts. The supposed negative treatment of women at the hands of Muslim men plays a central role in these representations (while conveniently distracting from the many ways the Indian state has failed to support women from all backgrounds). Since the late twentieth century, the Hindu right has targeted Muslim family laws, and their supposed ill-treatment of Muslim women, to argue for universal (read: Hindu) family and inheritance laws. Some on the Hindu right have even suggested that gender inequality in contemporary India stems from the arrival of the Mughal empire. These strategies allow right-wing Hindu nationalists to co-opt critiques of gender inequality in contemporary India for the sake of undermining the status of Muslims in India more broadly. Narratives of oppressed Muslim women draw on a long-established, globally circulating Islamophobic discourse that treats the status of women as an index of how “civilized” a social group is. Such anxieties about the status of women were a trope in civilizing missions going back to India’s colonization by the British, and continue to justify Western imperial missions in the Middle East and Central/South Asia (as numerous historians and anthropologists have demonstrated, including Lata Mani, Antoinette Burton, Mrinalini Sinha and Lila Abu-Lughod).

As the contemporary life of these narratives shows, binary distinctions such as civilized/uncivilized, oppressed/liberated, and public/private are highly portable, easily translated from one scale of comparison to another (what anthropologists call “recursion”). For example, longstanding distinctions between the “West” as “civilized” in comparison with “uncivilized” colonized societies (or, today, the “developing world”) can, in turn, be used by powerful groups within so-called “developing” countries like India to distinguish between more or less “civilized” citizens based on religious identity. The cruel irony of these recursive translations is that they enlist people in reproducing the very distinctions that, at other scales of comparison, are used to marginalize them. On the other hand, such interpretive practices can allow people to remake those categories by applying them to new contexts. In Shaheen Bagh, for example, a group of “housewives” domesticates the public space of a major road, and in so doing emphasizes that such public spaces were home all along.

The Shaheen Bagh protests invert representations of Muslim women as oppressed by the men of their community by centering a leaderless group of Muslim women who emphasize their status as women and as family members. Instead of being trapped at homes run by men who are not themselves full, “real” citizens of the nation, they present themselves as representatives of the nation by invoking their status as female kin. They draw on the language of family to describe their relations with fellow protestors. The older protesters are frequently described as “dadis,” grandmas, and visitors describe being addressed as betis, daughters. To those who paint Muslims as guests overstaying their welcome, these invocations of female kinship provide a different language of belonging in the nation state: grandmothers always ready to welcome you home. In claiming ties of intergenerational kinship, protesters draw on shared understandings of female familial solidarity. Such claims of kinship push back against the NRC, which requires citizens to prove citizenship via documentary evidence of property ownership and descent from male kin—documentation less readily available to women than to men.

At the same time, such invocations invert assumptions that female kin are subordinate or passive, shared across communities in India (and beyond). These aren’t just dadis—they’re described in the press as dabaang dadis, bold or fearless grannies. In invoking female ties of kinship, these dabaang dadis respond to the aggressive, austere models of masculinity that inform the Hindu right, where leaders emphasize a virility that derives from ascetic discipline. These are best encapsulated in representations of Prime Minister Modi, who lives alone, or in representations of the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Ajay Mohan Bisht, known as Yogi Adityanath, who dresses in the saffron robes of a mendicant. For these leaders, such discipline must also be applied to the nation itself, which must be defended via borders and bullets. Against this model, the women of Shaheen Bagh draw on longstanding ideas about home and family to experiment with other modes of belonging, one where citizens are strengthened rather than weakened through their relations with diverse others, where open-ended relations of pyaar, love and affection, draw citizens to the nation. When vigilantes chanting right-wing slogans fired at protesters, protesters responded with a nara, a protest slogan of their own, while holding signs that said “not bullets but flowers:” Desh ke in pyaaron pe phool barsao saaron pe (Let flowers rain on the heads of those beloved of the country).

In reframing the links between gender, kinship, and citizenship, Shaheen Bagh’s protesters are remaking the definition of secularism in India. Against those who seek to use religion to define who can call India home, offering, at best, a space of tenuous tolerance for “guests,” protesters at Shaheen Bagh and others are reimagining constitutional secularism as a kind of home, a space of belonging. This approach is beautifully encapsulated in images that circulated in the wake of the CAA’s passage, documenting efforts to create educational “constitution houses” that embody India’s constitution as a literal house, with key tenets providing the foundation, windows, and roof. Along the roofline, above the door, reads the words: “this home belongs to people of all religions.”