This research project examines the role of women in interreligious dialogue and peaceful co-existence in Indonesia, focusing on the activities of two organizations: Komnas Perempuan, or Komisi Nasional Anti Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan (National Committee against Violence against Women) and the Koalisi Perempuan untuk Keadilan dan Demokrasi (Women’s Coalition for Justice and Democracy). Both organizations were born out of pre-existing grassroots activism, launched after the 1998 collapse of Suharto’s New Order regime, and especially focused on protesting acts of violence against women. When large-scale communal violence erupted in May 1998, women, many of them ethnic Chinese, were among the primary victims. Although the society around them was still deeply rooted in misogynic ideas, the battles these women had waged for legal, religious, economic, social, and other forms of equality since the 1980s had started to bear fruit; new opportunities had opened to women, and debates about their legal rights had reached the public press and political platforms. In particular, women’s legal status—for example, in situations of domestic violence—had become stronger as activists convinced the general public of the negative consequences of such violence.

After 1998, as the nation transitioned to a democratic model, incidents of interreligious violence continued to break out across Indonesia. Radical Muslim groups vied for power and launched campaigns focused on religious beliefs, often targeting women’s social position and rights. While these groups failed to gain official political power, their ideological discourse has had significant impact and continues to fuel pervasive local conflicts. With government decentralization, local by-laws replaced the failed attempts to apply Shari’ah nationwide. Although in many cases these laws contradict Indonesia’s Constitution and national laws and have led to a plurality within the legal system, local governments (district/municipality, region, or province) can and do issue their own Shari’ah-inspired laws. In particular, these laws sometimes discriminate against women; a Komnas Perempuan report (2010) on 154 such laws found that 63 directly restricted women’s rights. Furthermore, their sheer presence has thrown debates on such issues as domestic violence back decades. This regression moved Indonesia’s diverse religious women’s groups to take action, and a variety of women’s organizations gathered under the umbrella of the Komnas Perempuan and one of its partners, the Koalisi Perempuan.

Facing the risk of being accused of importing Western feminist ideas, Komnas and the Koalisi stressed the fact that their work was based on the teachings of their respective religions. This approach resulted in women of different religious backgrounds working together, and sharing in serious religious reflection on how to address initiatives that strengthened women’s basic human rights.

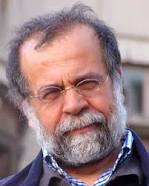

Research findings and individual observations have since confirmed that women played a vital role in reconstructing the nation and building stronger, more durable interreligious relations. For example, during his work as a member of the Komnas Perempuan subcommittee for gender and minorities, famous Indonesian women’s rights activist Kiai Husein Mohammad found that religious pluralism has to be learned and is often undermined by a local leadership that refuses to apply national rules of law. He found that political identities trumped the demands of living in a religiously pluralist environment and that women were the strongest forces in trying to break these pervasive patterns. Recent research by the members of the Shari’ah Department at Islamic State University (UIN) in Yogyakarta confirms that, especially at the grassroots level, male leaders will apply rules and laws they deem beneficial, even when they contradict national rulings or guidelines. Further, inconsistent application of local rules and by-laws disadvantages mostly women. How radical discourse has influenced public opinion can be seen in the June 6, 2015 Jakarta Post, which observed that, nowadays, more Indonesian Muslims are concerned about interreligious marriage than the harmful practice of child marriage.

Komnas Perempuan and Koalisi Perempuan are both national, interreligious organizations with local chapters across the nation that address women’s challenges. Their activities range from publishing research reports, academic analysis and reflection about local activities (e.g., Adeney-Risakotta), to grassroots initiatives. The Koalisi currently focuses on poverty, while Komnas deals with violence against women, legal pluralism, and poverty, among other problems. Komnas tailors its activities to national and local needs; for example, it has focused on women’s role in elections since 1999 and on the recent death sentence for female drug smugglers. Both organizations have been structured to strengthen women’s rights, promote religious equality, and break through such barriers as religious fanaticism, poverty, discriminating policies, and lack of legal clarity.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

For this Contending Modernities project, our guiding research question is:

How do these two Indonesian women’s organizations negotiate religious differences when addressing violence against women (e.g., domestic violence), legal pluralism, and poverty?

Consequently, sub-questions include:

What specific strategies do these women design to address issues of systemic violence, legal pluralism, and poverty?

How do these strategies connect to local and national programs and policies?

How are they translated into the relevant discourses of local and national leaders and policy makers?

How do the strategies contribute to the issues of interreligious living, interreligious dialogue, and civic peace making activities? Do they strengthen interreligious living?

The fact that these two organizations conduct activities at the national, provincial, and local levels makes them the ideal venue to study women’s strategies and instruments to translate local concerns into national contexts, and to see how the different levels of governance interact. In remote rural areas, in cities, and in developing areas, their work is defining the position of women in modern Indonesia and forging stronger bonds between religious communities.

This project is based on two premises: the reality that certain definitions and practices of interreligious dialogue are specific to the Indonesian context, and that women often play specific roles in this dialogue.

Existing literature on interreligious dialogue often discusses theoretical practices such as exchanging knowledge about each other’s religions. At the grassroots level such exercises might be too sophisticated, and populations tend to use religious symbols to support the integration or segregation of religious communities.

Women are among the most invisible actors in interreligious dialogue and civic peacemaking activities, in part because they often work primarily at the grassroots level. While solving social problems at the complex intersection between religion and culture, women are faced with pervasive biases, regardless of religion. Double burdens, ambivalent attitudes, and unrealistic expectations about women’s work and duties exist across religious lines. This project aims to map women’s influence as agents who strengthen interreligious relations while dealing with domestic violence, legal plurality, and poverty.

Despite the challenges they face, for many decades the Indonesian reality has proved that, faced with blatant conditions of injustice, women will not stay silent. Organized in a wide variety of religious and nonreligious organizations, they construct initiatives to counter the forces that diminish their rights and general wellbeing. The very existence of the two organizations under study testifies to this determination. For the Contending Modernities project, studying these two organizations will benefit the larger discussions of women’s roles in interreligious dialogue and yield information about specific strategies and methodologies. It will inform our understanding of the mechanisms underlying successful civic and interreligious peacemaking initiatives in the twenty-first century.