Mitri Raheb’s The Politics of Persecution: Middle Eastern Christians in an Age of Empires tells several profound stories of loss. One of those is the loss of the interwovenness of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities in the MENA (Middle East and North African) region before western Christian colonial forces violently devoured the lands of the former Ottoman Empire. Raheb’s account doesn’t romanticize the Ottoman period of diversity, which existed within a millet system, but instead shows how its demise brought into being an exclusionary and sectarian political logic.

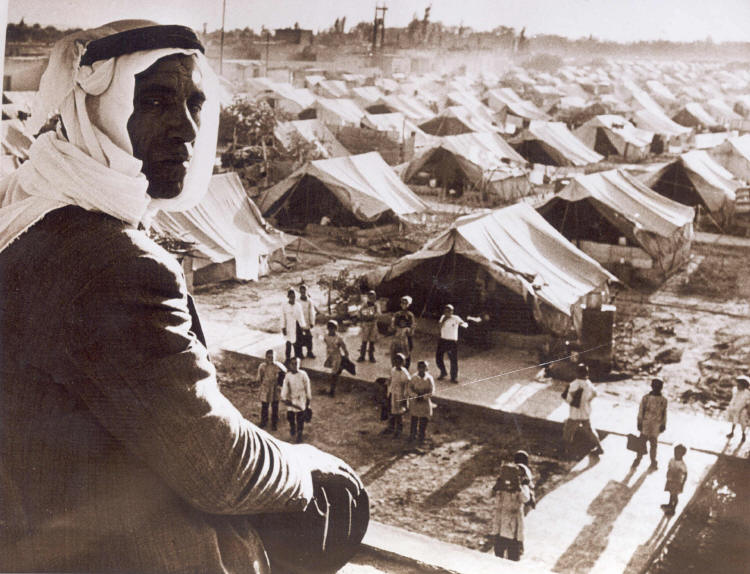

My remarks put Raheb’s critical account of “the politics of persecution” into conversation with the film ‘Til Kingdom Come (directed by Maya Zinshtein) to illuminate the continuous Palestinian Nakba (or catastrophe) of 1948, which also names the ongoing reality of Palestinian displacement. The Politics of Persecution captures the violence of European missionary and colonial administrations and contextualizes the manipulation and weaponization of Christian persecution for imperial agendas and designs, often under the guise of the protection of “religious freedom.” First, he tells the stories of massacres of Christians that didn’t enrage the colonial or neocolonial forces. If such massacres enraged them, this indignation was connected to expediency, utility, and geopolitical and ideological interests. His point is not that a commitment to religious freedom is ideological as a matter of course but rather that a concern with the plight of communities rendered “religious” has been used as a weapon and is manufactured around hegemonic objectives. When one takes away the utility of the weaponization of religious freedom and concern with religious persecutions, the ethical concerns vanish too. Raheb explicitly points to how and why concern with “religious persecutions” was invented as an integral dimension of imperial designs. In addition, he traces how confining groups along religious labels was deployed to forge the sectarianism that characterizes some areas in the MENA region, such as Lebanon. Relying on the notion of sectarianism as an explanatory framework for the analysis of conflict in the MENA region thus reconstitutes a colonial interpretive frame. Within such a frame, the protection and selective empowerment of various Christian denominations, such as the Maronites in Lebanon, was linked to imperial designs and vice versa. This selectivity persists to this day and is often generative of false analyses of how religion relates to the dynamics of violence (and, in the inverse, peace) in the MENA region.

Religious Freedom and the Secular in the Postcolonial Moment

Raheb’s analysis pushes against rhetorical and explanatory frameworks that render the “plight of persecuted Christians” as the outcome of a sectarianism that has supposedly been in place since the beginning of time. Instead, he traces how sectarianism itself was a product of European colonial and missionary intrusions into the region. Here Raheb’s storyline connects with the late Saba Mahmood’s analysis of the discourse of minority rights in Egypt. In Religious Difference in a Secular Age: A Minority Report (2015), Mahmood challenges secularist accounts of religion and violence. She argues that, rather than a panacea, secularism (as a part of a modernist epistemological colonial project) is the source of political violence that presents and cloaks itself as “religious.” The liberal secular as a discursive tradition is embedded within a parochial European Christian history and political projects, which is undergirded by orientalism. While Raheb does not engage with the critique of the modern/secular, his embodied and historical account conveys the violence that Mahmood’s theoretical intervention demystifies. This is especially the case when he zooms in on episodes of catastrophic violence, such as the Massacre on Mount Lebanon in 1860, a conflict that involved primarily Christians and Druze. Here, Raheb captures the tragic outcome of the colonial discourse of division and reification when he writes, “Geography could no longer tolerate more than one demography: either Christian or Druze” (37).

The liberal secular as a discursive tradition is embedded within a parochial European Christian history and political projects, which is undergirded by orientalism.

Further, as Elizabeth Shakman Hurd argues, the “promotion of religious freedoms” via governmental and intergovernmental organizations that monitor “religious persecutions” constitutes an international relations strategy intent on reconfiguring hegemonies in the presumed postcolonial moment. Raheb contextualizes this insight within a deep history of Christian intrusions into the delicate tapestry of the Ottoman MENA region via missions, colonial infrastructures, schools, and curricula. In a layered manner, Raheb reveals the epistemic and political violence—along with the mapping and controlling—that the deployment of “religion” as a boundary for identity and as a basis for human and cultural rights allows. As the critical study of religion, especially in its decolonial turn, has demonstrated, “religion” as a mode of an anthropological and comparative classification was born together with empire and the doctrine of discovery (e.g., Nelson Maldonado Torres). As such, religion has been co-constitutive with “race,” or with the logic of racialization, in the development of colonial empires. The story of Jewish Zionism is a part of this story. It is a project of settler colonialism in Palestine that is interwoven with western Christian colonial and imperial designs and has colluded with missionary expansionist moves into the region. The disregard for Palestinian lives (Christian, Muslim, or secular) has exemplified the manipulative nature of the discourses about religious freedoms and persecuted Christians. These discourses, further, are intricately related to Christian and Jewish theologies of restoration, end time, and redemption (e.g., Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin).

American Evangelicals, Israeli Settlers, and the Palestinian Christian

One of the critical points Raheb articulates is that naming violence as a “religious persecution” is misleading and glosses over the process of sectarianization born out of western Christian intrusion into lands previously under the Ottoman sphere of influence. Nowhere is this claim more evident than in the ignoring (and in the denying the validity of) the plight of Christian Palestinians amongst European and US empires.

As I read the Politics of Persecution, I was reminded of the film ‘Till Kingdom Come. The film portrays the consolidation of the political power of White Christian evangelicals in the US during the Trump era and the convergence of this group with the increasingly mainstream settler lobby in Israel. It focuses specifically on the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews. The film explores the apocalyptic theological worldview concerning Christian end-time prophecy that animates US Evangelical Christians’ commitment to Israeli settler colonialism. “The Jews” are a mere fetish, an instrument in this antisemitic drama, which proposes the necessity of a Jewish nation being established in Israel for the second coming of Christ to occur. At the same time, Jewish Zionist actors are happy to instrumentalize this toxic “love” to further entrench Jewish Zionist supremacist control over Palestine. The film also depicts a toxic intersection of the prosperity gospel and end-time theology, distorting the pivotal verse from Genesis 12:3 (“whoever blesses Israel will be blessed, and whoever curses it will be cursed”). In the Genesis verse, Abram is the subject of the cursing/blessing, but as the verse has circulated amongst this group in the US it has been decontextualized and treated reductively to refer to the nation of Israel or “the Jews.” The viewer glimpses how members of a church in a poor Appalachian community collect their small change to give to the Fellowship, believing their act of “blessing” Israel will bless them as a church and a community. Driving through a dilapidated community, seeing where people are living, and even commenting that some of the homes look abandoned, the Israeli Jewish leader of the Fellowship, Yael Epstein, is keen to deploy Genesis 12:3 to rationalize her fundraising efforts. This results eventually (in the course of the film) in a 5-million-dollar donation to “friends of the IDF” using the funds she has raised in Appalachia, amongst other places. She announces the check at a fancy gala in Hollywood. Yael manages to bracket the antisemitic theology of the pastor in the church. As he hands her the check, he comments on the wealthy Jews of Hollywood and how one day “soon” they will see their error.

Zinstein, the film director, is brilliant in not lecturing or telling but simply showing us the absurdities of the Christian evangelical and Jewish settlers’ alliances with one another and an array of political opportunists. In doing so, Zinstein shows us the how religion operates violently within American empire.

I now want to highlight a sequence in the film that recurred to me as I read Raheb’s book. In one scene, Zinstein arranges for a meeting of the evangelical pastor from rural Kentucky (aka Pastor Boyd) and Rev. Dr. Munther Isaac from The Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church in Bethlehem. Perhaps there was some sort of naiveté and hopefulness invested in this arranged meeting. Zinstein might have thought that a conversation between Pastor Boyd from Kentucky and Rev. Dr. Isaac, a Palestinian Christian, would somehow make Pastor Boyd see the suffering of Christian Palestinians and the plight of the Palestinians broadly. This would then puncture the myopia that comes with interpreting the world through an end-time prophecy. However, despite Rev. Dr. Isaac’s efforts to explain the concrete realities of dispossession and violence experienced by Palestinians, Christians, and otherwise, Pastor Boyd emerges from this meeting, declaring to the camera that “there is no such thing as a Palestinian!” This unbelievable sequence, where Boyd’s Christianity and all-consuming “love” of Israel and the Jews prevents him from seeing and hearing the story of another Christian person, connects with Raheb’s story in the book. In this instance, the phrase “Christian persecution” rings hollow. For Pastor Boyd, a Palestinian cannot exist because doing so would violate his ahistorical rendering of the world, one in which the land between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea can only be the land of Israel, and only inhabited by “the Jews.” This is why Pastor Boyd goes on to disturbingly claim that Rev. Dr. Isaac’s theology is antisemitic. For Pastor Boyd, the identity of who is able to count as a Christian goes unnamed, though the racial and imperial logic that undergirds this identity lies barely beneath the surface. Raheb examines the long history of this manipulative politics as a tool for advancing—under the pretense of protecting various Christian communities— specific imperial power agendas. In the case of Pastor Boyd, we see him blinded by his belief in the prophecy. This belief—and its embeddedness in an imperial and colonial framework—blinds him to the concrete suffering of his fellow Christians (and more basically, his fellow humans).

For Pastor Boyd, a Palestinian cannot exist because doing so would violate his ahistorical rendering of the world, one in which the land between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea can only be the land of Israel, and only inhabited by “the Jews.”

By moving from rural Kentucky and Pastor Boyd’s little church to the wider political context in which it operates, the film also shows us how this apocalyptic end-time evangelical theology has devastating ramifications for Palestinians. For example, the film depicts the mobilization of Christian evangelicals to withdraw US support of UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestinian Refugees) and to relocate the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Both these policy outcomes were eventually implemented. The story of pastor Boyd shows the importance of thinking intersectionally, in this case, about Whiteness, Christianity, and poverty, for understanding how, when, and in service of whom Christian persecution in the MENA region is raised as an issue of concern.

Indeed, the fact that Dr. Rev. Isaac is a Christian is the least relevant factor contributing to his persecution. Palestinian Christians are under attack, but they are targeted not because of their Christianity, but rather because of their Palestinian identity. Even if Pastor Boyd recognized Isaac as a fellow Christian facing an existential threat, the framing of the threat in terms of Christian persecution would still distort the analysis of settler colonialism, Jewish Zionist supremacist policies, and occupation. The deployment of religion and its extraction from a complex historical and political analysis obscures the explanatory frame that is needed to understand the persecution of someone like Rev. Dr. Isaac. By the same token, without scrutinizing the role of American empire in addition to the Christian restorationist theology and race, class, and gender within the US, we cannot fully understand Pastor Boyd’s lack of empathy. At the moment, “saving” Christians from “persecutions” in the MENA region is refracted through an Islamophobic and orientalist lens consistent with the “global war on terror.” The complicity and co-imbrication of Christian and Jewish Zionisms, amplified by orientalist tropes, totally obscure the reasons for the persecution of Christian Palestinians.

A Concluding Question for Further Discussion

I conclude with a question to open rather than close the discussion. Decolonial thinkers have spoken recently on the need for double critique, namely focusing externally on a critique of empire while also interrogating the traditions themselves through an epistemology from the margins (feminist religious hermeneutics, for example). How should such conversations unfold within the geographies of Christians in the MENA region and perhaps specifically in Palestine?