As a scholar of religion and politics interested in issues of race, religion, and gender, I found a compelling conceptual distinction in Black Dignity: The Struggle Against Domination that I believe can be useful beyond the United States (US) context from which Lloyd writes. This is the distinction between oppression and domination. In a subtle swipe (intentional or not) at Iris Marion Young’s “Five Faces of Oppression” Lloyd notes that “domination points to an ontological condition, rooted in its primal scene, whereas concepts like oppression, suffering, exploitation, injustice, and marginalization point to ontic conditions, specific harms in the world” (13). This is not to say that the ontic is therefore immaterial, but that we can’t rely only on it to point to the complex ways in which Black people continue to suffer under the regime of anti-Blackness. Consequently, Lloyd’s reading of the Black Lives Matter movement through a concern with the ontological dimension of domination as “an expansive apparatus” serves to demonstrate that anti-Blackness persists in the “ideas, habits, feelings, institutions, and laws” of American society (12). However, I would add that this is not only the case in the US, but everywhere, including places where the majority of the population is Black. That is, anti-Blackness is a borderless ontological condition that is bound by the geography of Whiteness to which even people of Color (including Black people) sometimes subscribe. Thus, in supporting the book’s big claim that the struggle for Black Dignity is the pursuit of a denied status that can only be realized through the struggle to achieve it (5), Lloyd critiques not only White multiculturalism but also the politics of Black respectability. In Lloyd’s view, the struggle to achieve Black Dignity cannot be fulfilled through the individualistic and myopic politics of multiculturalism and respectability. That is, the antidote to this form of politics is collective action.

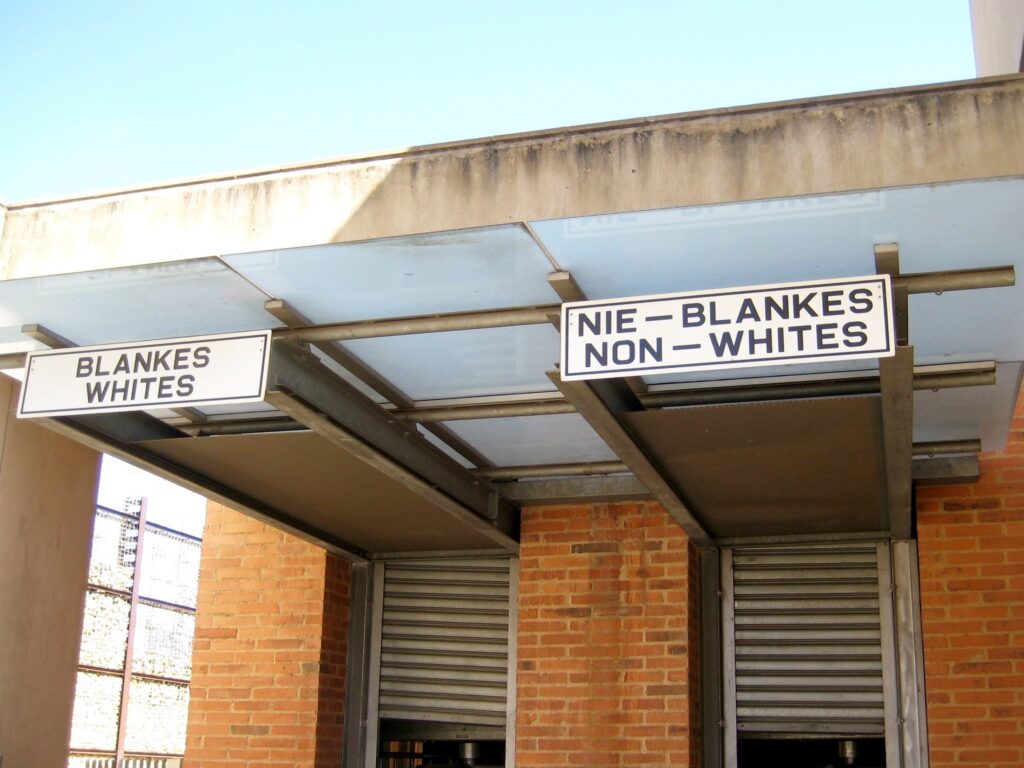

In South Africa, where I work as an academic and which is also one of the two places I call home (the other being Canada), there is a common refrain from the White enclave (both liberal and conservative) that Black South Africans should stop blaming apartheid for their current condition since we have had freedom for over twenty-six years. From Lloyd’s perspective, the conditions of anti-Blackness continue beyond the overt system of apartheid in South Africa precisely because the ontological conditions that perpetuate anti-Black racism have continued unabated. Bouts of overt racism in the country, according to the logic of domination, are only more visible manifestations of the deeper reality of marginalization. According to Lloyd, these examples of overt racism illustrate is the fact that “anti-Black racism is not just about bad choices, or about people who failed their diversity exam. It is at the center of everything, for everyone” (xi). This means that Black people everywhere, everyday are being disappeared from spaces where their dignity is not recognized, even when they try to play by the books and be “respectable.” Whether it is at a school, university sports field, corporate office, public park, restaurant, farm, or private home, to name just a few, to be Black is to be denied dignity, full stop. Moreover, anti-Black racism is not just about Black people, but about everyone because we all participate in domination.

Anti-Blackness is a borderless ontological condition that is bound by the geography of Whiteness to which even people of Color (including Black people) sometimes subscribe.

As such, in the context of the US, according to Lloyd, what the Black Lives Matter movement has chosen to do in response to this denial of dignity is to channel Black Rage and Black Love, redefine Black Family, and use Black Magic, all in the pursuit of Black Futures. Lloyd organizes the chapters of his book around these topics. Of particular interest is the observation that, instead of hope, “those who struggle for Black justice today talk about Black Futures, a label that joins a sense of the anti-Black world’s demise and the imperative to imagine radically new ways of living together” (96). While Black Futures might sound utopian, their orientation is anything but; fueled, as it is, by the rage of ending domination and instituting the end of the world. In the South African context, one is reminded of Steve Biko’s critique of liberal assimilation, especially the assumption that nothing is really wrong with South Africa except for the lack of integration of everyone into the same system. That is, colonialism and apartheid were merely the bad fruits of what should have been Black people’s good encounter with White European civilization. From the perspective of the liberal enclave, apartheid, in particular, hindered the supposed Edenic system of governance that should have been the result of European modernity brought to Africa. Western modernity was a good thing, but it was the Afrikaans White nationalists who spoiled everything. Therefore, all that needed to happen, instead, was to remove the bad ailments of White nationalism. Of course, this view failed to account for how the whole civilizational mission of Europe had obliterated Black South Africans out of humanity—out of dignity.

Therefore, for Biko, Black Consciousness was the answer to the domination assailing Black people from the sides of both the conservative and liberal enclaves, which treated Black people paternalistically and without dignity. Hence, when Chumani Maxwele threw human feces at the statue of Cecil Rhodes on March 9, 2015, it clearly demonstrated the indignity that Black people of South Africa feel they are being subjected to each and every day; White arrogance everywhere. While Maxwele might be singled out for his act that spawned a whole set of events, now labelled Fallism, he did not act alone. He was supported by a whole community of Black students, scholars, activists, and White allies who, although out of view, were very much central to the enactment of the shared desire to be free from the monumental White arrogance represented by the statue of Rhodes, among many others, thus pointing us back to Lloyd’s argument concerning the importance of collective action in the pursuit of dignity.

For Lloyd, “if hope cannot be shared, it is mere desire, what one individual covets” (103). Thus, the only way for Black people to achieve freedom and, consequently, dignity, is by acting collectively. The Fallist movements in South Africa (#RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall) were an example of such collective action, including what it can achieve now and in the future. This collective action is also what Biko called for when he and his colleagues challenged White liberalism in all its forms and showed how it was beholden to the same anti-Black domination model as its conservative counterpart. In calling for self-reflection on the part of Black people regarding their own condition of consciousness about being dominated, Biko demonstrated the kind of dignity that Lloyd points out in relation to some key figures of the Black American Tradition, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Frederick Douglas, whom he wrestles from the grip of Black respectability and White multiculturalism.

As is evident from this reflection on Black Dignity thus far, there are several intersecting themes and concerns that the book covers. At times, it feels like the connections between chapters are neither strong nor well clarified (the logic of beginning with rage and ending with magic is never clarified); and that even some of the differences in ideological orientation are too stark and binary in their articulation (that between philosophers and social movement organizers, for example). However, in reading the book with patience, what appear as weaknesses actually reflect very principled methodological choices that remain true to the complex reality of pursuing Black dignity on the ground, and in a way that speaks to Lloyd’s engagement with the activists of the Black Lives Matter movement. That is, the struggle against domination and the pursuit of Black dignity are multiple in nature, and sometimes these struggles coalesce with other struggles, and sometimes these struggles bump heads. Lloyd makes this point evident in the ways in which he draws on contrapuntal examples of key Black leaders in the American context who might not seem to fit together (Martin Luther King, Jr. and Samuel R. Delany, for example), but when read together can be shown to be struggling against domination and concerned with the pursuit of Black dignity. For the reader, this means that in making sense of these struggles, including how they speak to domination, one has to make connections in a way that resonates with one’s reality. In other words, one has to engage in a process of discernment—i.e., struggle with oneself and others in line with the book’s argument that Black dignity arises out of struggle. In the case of King, Jr. versus Delany, for example, this means one has to appreciate their differences and understand their struggles contextually while embracing their thought collectively as part of the greater movement towards Black dignity. Moreover, if one is really committed to freedom and not domination, some stark binaries are necessary in order to name that which kills Black Dignity and affirm that which builds such dignity.

The only way for Black people to achieve freedom and, consequently, dignity, is by acting collectively.

In the end, Lloyd leaves us with a morsel of truth in classical philosophical style, but without the pretense of having given the Truth. And this is the observation that the pursuit of Black dignity may appear inchoate, confusing, tragic, and seemingly only reiterating that our struggle is in vain. But, as Lloyd writes: “Black people struggle, and this struggle is our dignity” (xiii). This statement is not to be taken lightly, because in its embracing of a negative, it affirms a key aspect of what the book highlights: “Black humanity and dignity requires Black political will and power” (21), a “new moral and political stance” (22). Such a stance is about foregrounding the precision of domination that has been perfected in anti-Blackness, even while we hold true the argument of interlocking systems of oppression. We do this because we have the most clarity about anti-Blackness the world over (14). Anti-Blackness informs not only the logic of racism globally (finding expression in places as varied as Brazil, India, South Africa, Tunisia, and Ukraine, to name just a few where expressions of anti-Black racism have recently surged), but also domination broadly.

However, this argument raises an important question for solidarity and collective action: Does this mean that for any other oppressed group, anti-Blackness is still the normative primal scene of domination? Here one can raise the issue of class, gender, and sex difference (amongst many others) as one of many primal scenes of domination for a specific set of people. However, I think that this would be to misunderstand Lloyd’s argument in the same way as those who misunderstand the Black Lives Matter movement as problematic because, in their view, all lives matter. Despite claims of equality and the dignity of all people, Black people continually find themselves in indignity, even where they constitute the majority. This can’t be mere coincidence, but an ontologically driven reality that requires that we rethink the dismissal of race politics as foundational to modern politics. That is, and this is a provocative claim: for Black people, collective action for dignity starts from our racialization. As those who are dominated, we are best positioned to articulate strategies and radical imaginations of anti-domination; collective anti-Black resistance against domination doesn’t have to be the terminal point, but it has to be a point of departure.