When I teach classes on ethics to my graduate and seminary students, I routinely explain that I want them to include a respectful affirmation of human worth and dignity as a core dimension of the vision for ethical human communities that they espouse. I insistently tell them that such an affirmation should be explicit in the ethical leadership they offer in their professional and ministry settings. Then I usually punctuate my insistence with a slightly overdramatic warning that in actuality I will expect them to develop a much more substantive moral vision for human social relationships and ethical leadership practices than the minimal baseline requirement of a respectful affirmation of human worth and dignity. After reading Vincent W. Lloyd’s Black Dignity: The Struggle Against Domination I have come to realize the wrongheadedness in this warning to my students. Lloyd’s meticulous, in-depth exploration of the ideas and lived politics required for an authentic definition of dignity proves me shamefully mistaken in so dismissively and unilaterally claiming the insufficiency of an ethic that solely attends to human dignity. I am particularly drawn to Lloyd’s analysis of Black love as a crucial contributor to that definition of dignity and how it incorporates the politics of gender and sexuality, although I differ on his deployment of the ideas of Black nationalist Eldridge Cleaver as a useful resource for envisioning Black dignity.

I first want to note how this text startles me over and over again with its skillful art of interpretation of fundamental moral notions that range from benchmark concepts in social and philosophical ethics such as hope, family, and freedom, to its excavation of recent cultural theories of multiculturalism, Afropessimism, and rage. Always in service of illumining the meanings of Black dignity, these concepts are analytically contextualized within Black thought and activism. The conversation between theory and activist practice flows in a synergistic relatedness that demonstrates their complete interdependence and, at times, renders them indistinguishable from each other. A steady unraveling of the meaning of human dignity does not occur in this contextualized Black theory-practice treatment of constituent elements of human dignity. Lloyd veers away from a standard academic mode of engagement to which one might be accustomed. This form of engagement is usually composed of a series of intellectually dismembering critiques that are placed on display. It can leave the reader with the task of trying to knit all of the unraveled concepts back together in order to glimpse the whole of Black dignity as a static social good. Instead, Lloyd creatively reveals Black dignity as social movement work, more precisely, as Black freedom movement work.

The notion of love serves as one example of a core conceptualization that reveals Black dignity. Black love provides evidence of Black dignity, Lloyd argues. I have chosen the example of love because of its ubiquity both in my field of Christian ethics and in the language of activist leaders of several of the contemporary social justice movements I frequent. Declarations about the need for love are often asserted by those leaders as they try to respond to the dire consequences for so many in our communities of proliferating, hate-filled right-wing Christian political agendas. It is difficult to overstate my concern about the ways in which claims of love can function in U.S. public life to diminish attention to abuses of power and sustain a diversity of dangerous Christian hypocrisies, such as in situations of domestic violence, clergy sexual abuse, or idolatrous love of nation used as an excuse to legislatively terrorize transgender children.

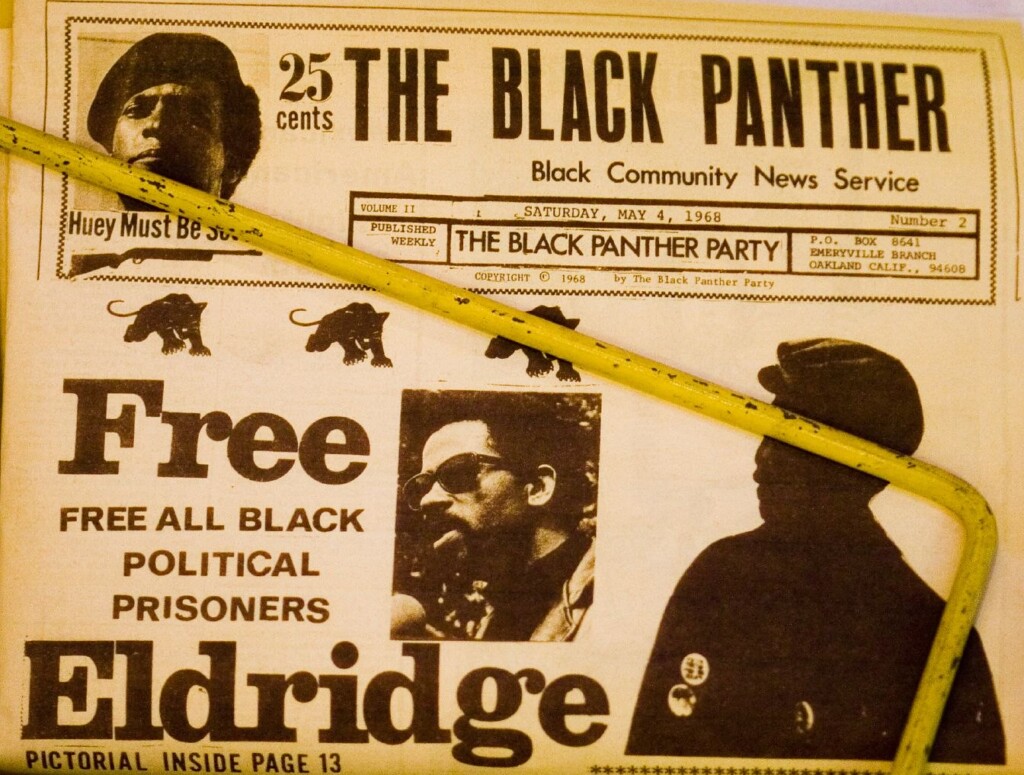

In its dynamic reveals of Black dignity, Black love emerges as a struggle for freedom that Lloyd grounds in the message of Martin Luther King, Jr., “a prophet of love” (58), together with ideas from Black power advocates Eldridge Cleaver and George Jackson. Although it primarily focuses on these figures, the chapter on love also analyzes other approaches, such as those from Black feminists Audre Lorde and Alice Walker and Black nationalist activist Assata Shakur, as well as Black feminist bell hooks in other sections of the book. The text presents a range of examples from King accompanied by correctives of simplistic readings of him. The discussion of King enables us to focus on the ways in which Black love requires both the necessary constraints of justice and the primacy of struggling for freedom in order to further the process of Black dignity. I experience relief and deep gratitude for Lloyd’s emphasis on how love talk—especially when King is invoked—can drain away any authentic moral meaning and exasperatingly implant a false sense that political injustices are easily resolved if we just love one another. For King, as Lloyd stresses, justice functions as a necessary corrective dimension of love. The contrast between King’s Christian views and the Black power positions of Cleaver and Jackson are narrated as part of a particular historical context rather than represented as a destructive rivalry. For Cleaver and Jackson, “Black love requires a hard break from wrongly ordered loves” (66) that are rooted in anti-Black racist and capitalist domination.

I experience relief and deep gratitude for Lloyd’s emphasis on how love talk—especially when King is invoked—can drain away any authentic moral meaning and exasperatingly implant a false sense that political injustices are easily resolved if we just love one another.

It is the sexual politics of the “wrongly ordered loves” of Cleaver and others in that 1960s Black nationalist movement that I find extremely troubling. Lloyd bravely engages their sexual politics but may underestimate the misogyny there and how it undermines Black dignity. He points out Cleaver’s focus on White women and his love for his White woman attorney that are articulated in Cleaver’s Soul on Ice and written from his prison cell. As Lloyd explains, Cleaver’s confrontation with how his own loves were disordered involved shifting away from advocating the rape of White women as an important political tool against the White man. For me, Lloyd’s understanding of Cleaver’s assaults as disorder or wrongly ordered love is not a fitting description. I am mindful of how at the beginning of Soul on Ice Cleaver admits to perfecting his technique as a rapist by attacking Black women before he moved on to White women. There is also a long allegorical section at the conclusion of the book with admissions of brutality against Black women by an “Accused” Black man. Simultaneously, in this concluding allegorical section, Black women are depicted as culpable in the abuse they receive because of the multiple ways they supposedly provoke it, such as their alleged love of White men and concerted betrayals of Black men.

Although these examples are not included in Lloyd’s account of the ideas about Black love that Cleaver’s Soul on Ice contributes to Black dignity, they are relevant to the issues of gender, sexual politics, and freedom that he invites us to engage. I am deeply appreciative of the subtle yet profound repudiation of the dignity-denying racism of mass incarceration in how Lloyd compels us to think about freedom through the lenses of someone who is in prison. Cleaver’s perspective may exemplify the struggle for freedom from anti-Black racist and capitalist domination. But it also stresses a certain kind of domination of Black women by maintaining a Black androcentric worldview as freeing. While I must reiterate that Cleaver does eventually disavow rape, I find that I cannot stop thinking about the Black women on whom Cleaver practiced his tactics of rape. I am also stuck on my disdain for the idea that a love letter to a White woman lawyer addresses the impact of the rapes he carried out against White women after practicing on Black women. The significance of the misogyny in Soul on Ice lies not merely in what Cleaver fails to express about his impact on the lives of the women he sexually assaulted, or includes in his portrayal of women as blameworthy for intimate abuse. The consequences stretch beyond the words uttered in Cleaver’s gendered, homophobic rantings about “the Black homosexual” in his critiques of Black novelist and activist James Baldwin. The reinforcement of this misogyny must be interrupted because of the wide influence of this Black manifesto within Black political culture, history, and studies. Lloyd’s discussion of it as a resource for understanding how Black love informs Black dignity motivates me even as I strongly differ on this point. It reminds me of the urgency to interrupt the misogyny in certain iconic Black power paradigms that prove how the personal is so very political when the history of Black thought and activism are constructively engaged.

Cleaver’s perspective may exemplify the struggle for freedom from anti-Black racist and capitalist domination. But it also stresses a certain kind of domination of Black women by maintaining a black androcentric worldview as freeing.

Lloyd’s intellectually provocative and complex social analysis of love will not allow me to stop probing and revisiting an understanding of how freedom practices inform Black dignity movement work. How do we count the gender justice costs in the struggles of that movement work? More importantly, when do we identify some of those costs as too high to be included in the process of how Black love constitutes Black human dignity? These questions represent the kinds of opportunities to wrestle with deep and contextualized meanings of human dignity that I am now excited to centralize in my teaching of ethics. Indeed, I look forward to addressing their wide-ranging gender and sexuality implications in my classes, particularly with my Black and Brown students in a state prison for men where I routinely teach. We often discuss moral conceptualizations in Black thought and activism. Undoubtedly, as we do so, there are opportunities to experiment with how freedom from domination might be embodied in our classroom interactions. Honestly, however, I must admit that I am not sure of the precise steps to take to authentically claim Black human dignity as Black freedom movement work at the center of our theory-practice learning in that male prison space. But I know that the students and I are committed to figuring it out, and I am methodologically inspired by Lloyd’s Black Dignity: The Struggle Against Domination in such a pursuit.