On May 30, 2020 Eyad al-Hallaq, a young Palestinian man from East Jerusalem who was on the autism spectrum, was shot and killed by Israel’s border police. Al-Hallaq was on his way to his special needs school when two border police officers decided he was carrying a suspicious object and ordered him to stop. Terrified, Eyad started running. The officers chased him and opened fire. He fled into a nearby garbage room where a guide from his school tried to defend him, explaining to the officers that Eyad had special needs. There, in the garbage room, lying on his back, hurt from the first gunshot, the officers shot him again from close range. All that al-Hallaq held was a COVID mask and a pair of rubber gloves.

Eyad al-Hallaq was killed five days after George Floyd was brutally murdered by Derek Chauvin, who pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds while two other officers helped to restrain the unarmed man, and a fourth prevented bystanders from intervening. George Floyd’s death ignited dozens of protests and solidarity acts across the U.S. and around the world. These protests were not only against his murder, but also against the wrongful deaths of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and the many others who have been victims of police brutality and systematic racism. While these protests are part of a long struggle, Floyd’s death generated, more than ever before, multiracial coalitions to fight against anti-black racism and ample conversations about the racist legacies and structures of the U.S.

Eyad al-Hallaq’s death did not stir up much debate amongst the majority of the Israeli Jewish public regarding engrained forms of ethnoreligious supremacy, which also manifest in recurring acts of police brutality against non-Ashkenazi Jews, such as the Ethiopian Jewish community. Among the many demonstrations by the Israeli-Palestinian public, a shared Jewish-Palestinian protest occurred in Tel Aviv on June 6, 2020, which took up al-Hallaq’s death, the Israeli occupation, and the annexation of Palestinian land. Protesters held signs saying, “Palestinian Lives Matter,” “I hope I don’t get killed for being Palestinian,” and pictures of al-Hallaq stating, “This is the face of the occupation.” These signs, as well as the Palestinian flags held in “Black Lives Matter” protests across the U.S., should not be read merely as a nod to current events or isolated acts of solidarity, but rather as calls, in Israel-Palestine and in the U.S., to make broader connections between interlocking systems of oppression very much associated with the dark and violent legacies of modernity’s multiple isms—militarism, imperialism, globalization, capitalism, and sexism. These isms interact with one another to oppress people of color, or who Fanon referred to as “the wretched of the earth.” While all these isms constantly interact, in this blog post I will be focusing on the interlocking of militarism, sexism, and racism. This provides one example of why it is important to connect social struggles to broader discussions of oppression, domination, and liberation.

This is not a call to equate the struggle of Palestinians with that of black and brown people in the U.S. Nor is it a call to reduce either group to their struggles. Such an equation indeed gestures to the ways in which Ashkenazi Euro-Zionism can be assimilated into a global analysis of whiteness but conceals the many ways in which Jews (including European Jews) are not white (as discussed in Atalia Omer’s recent book, Days of Awe). The construction of Jews as white, as Omer shows, has deep roots in the history of modern Christian Europe in which both Muslims (employed interchangeably with “Arabs”) and Jews functioned as the “other.” European Zionism enshrined in racialized Israeli nationalism has relied for its establishment and perpetuation on operationalized orientalism, eurocentrism, and settler colonial frames. As a result, Jews are no longer the “other” of Europe. They (white Ashkenazi Jews) embody its ills. They are no longer “the barbarians.” They became assimilated into whiteness and civilizational discourses. The dichotomy between the barbarian and the civilized later enabled Ashkenazi hegemonic discourse to construct Israel as a “villa in the jungle” (a phrase coined by Ehud Barak while acting as Israel’s Minister of Defense), differentiating it from its geographical region of the Middle East and associating it with Europe and the US. As Omer demonstrates, these processes must be contextualized, historicized, and deeply explored if one’s hope is to decolonize Judaism and reimagine it in solidarity with Palestinians.

Many of the Israeli Jews who attended the protest in Tel-Aviv would probably be perplexed by the idea of decolonizing Judaism and relinquishing Zionism. Many, in fact, held signs protesting the death of al-Hallaq and the occupation in the name of Zionism. While I too share the emotional difficulty involved in these debates on decolonizing Judaism, connecting Eyad al-Hallaq and George Floyd—East Jerusalem and Minneapolis—helps clarify how these two struggles are entangled with one another via race, militarism, and sexism. Zionism’s reliance on a nationalist discourse of self-actualization reveals Zionism’s modernity. As such it is entangled and implicated with modernity’s other creations, including race, which is reflected in its political project of bolstering Jewish supremacy. The Israeli occupation is an expression of modernity’s dark legacies but in complex ways that defy simplistic explanations and analogies. It also cannot be denied that for some Israel is also an expression of religious longing, and the precise relation between this longing and the modernist history of Zionism as a political movement and its realities needs to be interrogated. The occupation does not only oppress Palestinians, but also, albeit differently, oppresses non-hegemonic Jewish groups, women, and the LGBTIQ community, and sustains Israel’s racial formations and heteropatriarchy. This is especially true for groups who challenge the binary of (white Ashkenazi) Jews versus non-Jews, such as Mizrahi and Ethiopian Israeli Jews. Amongst this latter group, those whose identities intersect with other social groups who suffer ongoing discrimination, such as women and/or LGBTIQ persons, face unique and particularly harsh forms of oppression. Their struggles for equality should therefore be inseparable from the question of the occupation much as Black Lives Matter should be inseparable from the MeToo movement. All of these struggles (including along class lines) are bound together by the broader framework of militarism, racism, and sexism. But, importantly, they cannot be reduced to their oppressions.

Only five years ago, in 2015, thousands of Ethiopian Jews protested in Israel against police brutality, carrying signs stating: “We are the right color it is the world that’s gone crazy,” “I am black but transparent to society,” “blacks are only good for war,” and “I’m black, don’t make it a bad thing.” The Jewish-Ethiopian community in Israel suffers from “over-policing.” The percentage of indictments against Ethiopian Israelis is twice their proportion of the population. In 2015, the percentage of Ethiopian minors sent to prison was almost ten times that of their proportion to the population. Over-policing is a clear manifestation of a militarized society in which groups that lack political and social power are suspected of defying the hegemonic order. Bryan K. Roby provides another example over-policing, this time against Mizrahi immigrants. He has shown that in the early days of the Israeli state a constant police presence was maintained in the Maabarot (transit camps for new immigrants) in which most of them lived.

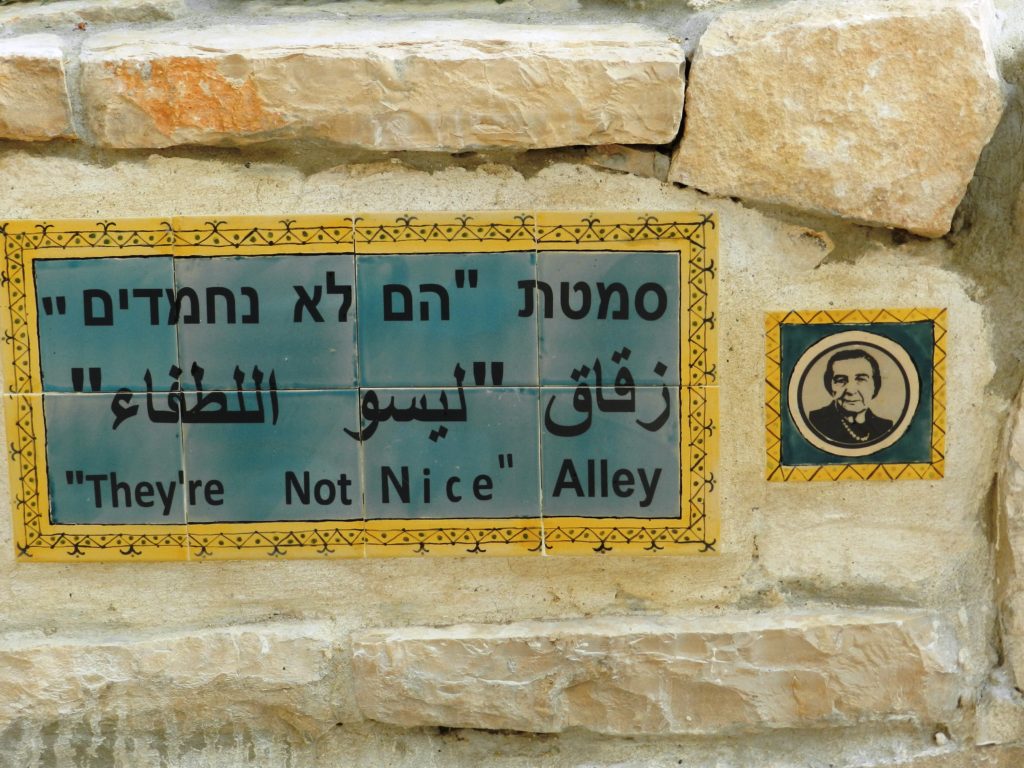

While the connection to “Black Lives Matter” might seem conspicuous, it has not been systematically researched or even widely referred to by Ethiopian Israeli protesters themselves. It has, however, been made by Mizrahi protesters who recognize how the European Zionist elites and institutions intentionally separate them from their Islamic and Arab linguistic inheritances and cultural practices. This separation effectively creates a separation between them and Palestinians. During the 1970s, Mizrahi protestors took inspiration from the black protest movement in the U.S., naming their movement “the Black Panthers.” The Israeli establishment’s reaction to these protests was highly aggressive. The establishment prevented the Mizrahis from protesting, claimed that they were prone to criminal activity, and held their leaders in preventive detention. At the time, the prime minister Golda Meir declared that the Israeli Panthers were “not nice.” In their response, Mizrahi protestors highlighted how the same establishment which discriminated against them sent them to fight on its behalf, proclaiming that “in the [Suez] Canal we are all nice.” This was echoed in the signs carried by Ethiopian demonstrators in 2015, which stated, “blacks are only good for war.” The border police—the branch of the police whose officers shot Eyad al-Hallaq work—are primarily Ethiopians, Druze, Bedouins, and Circassians. By enrolling minority groups to serve in combatant roles, the Israeli hegemonic establishment offers these groups a false sense of belonging and a never-fulfilled promise for equality and assimilation.

The Israeli border police also takes pride in enrolling female soldiers in combat roles. Women’s integration into combat roles within the army has become a source of pride and an arena for feminist activism. The feminist struggle that advocates for women’s role in the army is framed by activists mostly as a clash between religion and gender. This binary, much like the Jewish-Palestinian binary, renders the context in which such exclusion occurs unimportant and fails to make broader connections between women’s roles in the army and Israel’s multiple forms of segregation and exclusion, the most conspicuous manifestation of which is the occupation. By focusing on the exclusion of women in the army and not on the institution in which it is enacted, feminist activists can fight for women’s equality in the army without questioning the role of the army in affecting women’s status in Israel. But it is Israel’s militarism and its commitment to national security that best explains Israel’s lack of commitment to women. Strong links have been identified between conflicts, militarization, male hegemony, and hierarchies of gender and race. In a militarized society like Israel, security is often used to justify unequal social relations, and policymaking and civil discourse are made subordinate to security discourse.

While in the U.S. people might not feel the daily burdens of living in a conflict zone, a militarized society is not unique to Israel. The U.S.’ imperialist-capitalist ambitions are not only evident in its sending troops around the world under the pretense of maintaining order and security, nor in its efforts to uphold the Israeli occupation. As Judith Butler suggests, military violence and its murderous capacity to eliminate whole communities, even when enacted outside the geographical boundaries of the U.S., is symptomatic of deeper patterns of dehumanization that render some populations (domestic and international) ungrievable. In other words, for black lives to matter, the deaths of “others” need to matter. Militarism can, therefore, be thought of as the antithetical to solidarity because it not only dehumanizes the other but also separates and compartmentalizes different groups and struggles and silences them in the name of protecting the public from the threat of violence it associates with them.

When Amy Cooper called the police to tell them “there’s an African-American man threatening my life” in Central Park, she tapped into the intersection between militarization, racism, and patriarchy, activating them by weaponizing her white femininity. These systems of domination work together to paint a picture of a helpless white woman being attacked by a black “savage.” This image of the black man as imbued with threatening, unbridled, and aggressive sexuality is a deeply familiar racist stereotype. Its other half is the modest and pure white woman. The image of a white woman being harassed by a black or brown man is not confined to the U.S. Arab men are often described as trying to lure innocent Jewish girls or kidnap them into unwanted relationships. Similarly, as demonstrated by Raz Yosef, Zionism established the Mizrahi men as sexual predators who are intellectually and culturally inferior to white Ashkenazi men. Maintaining national resilience demands control of both women’s sexuality (by enacting patriarchy through sexual abuse and discrimination) and of black and brown men’s hypersexuality (by brutally policing them), as their mere being embodies a constant threat. Reading the case of Amy Cooper through the lens of multiple interlocking systems of oppression as exemplified through the case of Israel-Palestine also points to the connection between Black Lives Matter and the MeToo movement. This connection underscores that #metoo cannot be the commodity of white female celebrities but rather must be thought at the intersection of other marginalized peoples. Similarly, #blacklivesmatter should also include intersections such as #blacktranslivesmatter.

Understanding that racism, sexism, imperialism, globalization, capitalism, and militarism are interlinked means we cannot myopically call to eradicate one while upholding the other. Israel-Palestine is only one site of these broader connections, but its integration into the conversation helps demonstrate the need for an intersectional lens that interrogates how multiple sites of domination operate to determine whose lives matter. This intersectional lens not only draws a line between Minneapolis and East Jerusalem, but also compels us to deeply examine our own positions within systems of power and oppression. Only then will we be able to further our struggles against these interlocking sites of domination more globally in the pursuit of justice and liberation.

מערכות כוח ודכוי אכן.קשורות זו בזו והן רעה חולה גולבלית

הבנת המקורוח והקשרים.בתופעה הנוראה.עשויה לתרום לפתרון.

מאמר מעניין וחשוב ביותר