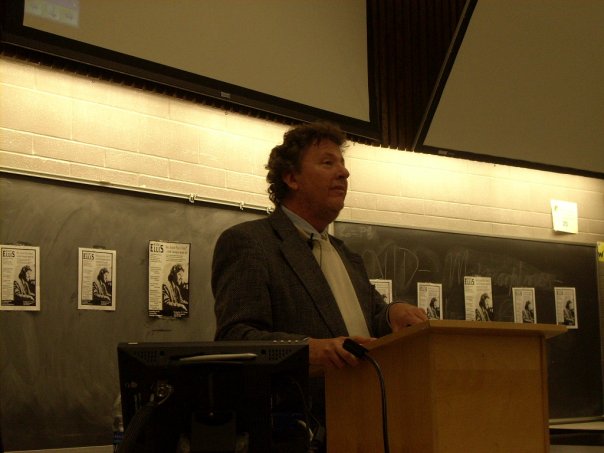

In the Winter of 2010 Marc Ellis was traveling through Canada on a speaking tour. Sponsored by the local chapters of Independent Jewish Voices, he was presenting his new book Judaism Does Not Equal Israel in all the major cities around the country. When I insisted that he pass through my little frozen prairie, the isolated city of Saskatoon, he resisted. At first, I was surprised. Given that he was a person who had traveled to remote places in the Global South to engage in intercultural liberationist dialogues, places “where no Jew cares to visit and/or was ever invited,” as he used to say, his resistance to visiting Saskatoon was puzzling. I thought perhaps it was the cold that was keeping him from accepting the invitation.

To convince him, without understanding yet his reasons, I tried to guilt-trip him, noting that I had survived the heat of Waco, Texas where I lived for a year studying under his guidance (from then on he insisted that I call him “Dr. Ellis,” a practice I maintain until today.) But then he told me he did not mind the isolation or the weather, rather he was worried about risking my job as a first-year professor in a tenure-track position. He wanted me to be safe. I became even more puzzled. For an intellectual who had brilliantly interrogated notions of Jewish safety—remaining steadfast in building a theology of solidarity with Palestinians inspired by the creative instability of Global South struggles, even when that led to him risking (and ultimately loosing multiple times) his job and livelihood—the concern for my job security in Jewish Studies in North American academia seemed a contradiction. Yet, it was not. Dr. Ellis was one of the intellectuals who was able to sustain a deep, audacious, and indefatigable commitment to structural critique and true care for the individual human beings he encountered. He was actually fascinated by the role that one single human being, whatever his/her/their positionality could play, as he used to say “when presented by a challenge at the right time.” This virtuous dialogical play between structural critique and deep interest and care for the individual who could intervene in history and make a difference was the basis of his pedagogy, his mentorship, and his scholarship, which aimed at a contemporary renewal of the prophetic.

Renewing The Prophetic

We spent uncountable hours over the years and across the world discussing—via e-mails, phone calls, skype, and then zoom meetings—what I understood as a tension in our views. Trained in structural critiques, I tend to minimize an understanding of history based on the actions of great individuals. Rather, I contend that historical changes require the right material and epistemological conditions of existence, are propelled by social movements that individual leaders interpret, represent, and systematize. But in only a few instances are these individuals the main factor in producing revolutionary outcomes. Furthermore, just to tease Dr. Ellis, one of the few Jewish scholars in the US who took thought emerging form Global South seriously, I called his understanding an “American trait” based on idealist individualism. Today, however, I am not so sure.

Dr. Ellis was one of the intellectuals who was able to sustain a deep, audacious, and indefatigable commitment to structural critique and true care for the individual human beings he encountered.

“I would love to think of Marc as a product of the American Jewish community” Susannah Heschel once wrote in the preface to a book honoring Dr. Ellis’s work that was co-edited with Susanne Scholz. “[B]ut I wonder if we deserved the credit” (i). In contrast to an American Jewish community fearful of contradictions, haunted by memories of not only their own dispossession but also their implication in the dispossession of others, “the stance of Marc is a prophetic one.” Heschel, one of, if not the leading voice in Jewish thought today, was making an illuminating point. Heschel, as a deserving inheritor of a longstanding tradition of Jewish conversations with some of the most dehumanized communities in the US—which included her father, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, marching with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, but has been reproduced in her own work until this day—simultaneously pushes us to interrogate both the contemporary role of the American Jewish establishment in global conversations about injustice and the variety of sources Dr. Ellis was employing to develop his prophetic stance beyond even the American context.

On the one hand, Dr. Ellis was deeply American. His model for the prophetic held a special place for individuals who can make a historical difference and is largely represented by the omnipresent figure of Bob Dylan (MLK Jr.—among others—was a close second). In his formal degrees he was trained in American religious history and sociology. He was deeply influenced by the anti-Vietnam protests, the Cold War, and the US Catholic tradition. The latter led him to spend a year working at Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker in New York City where his diaries became his MA thesis and first book. This influence is also clear in his biography of the priest Peter Maurin, his PhD dissertation, and later, his second book. But it was precisely his work among Catholics that led him to launch and direct an MA program in Peace and Justice Studies at the Maryknoll Seminary. Here, his Jewish conviction paired with the platform of an alleged Catholic universality helped him interrogate what had become a Protestant and Jewish American sectarian parochiality. After Maryknoll sisters were kidnapped, raped, tortured, and murdered by US-sponsored forces in El Salvador, Dr. Ellis may have understood that the struggle against poverty and racism in the US went beyond the “borders” of the nation-state. They needed to be encountered in the “frontiers” of US imperialism, both internally and externally.

Going Global

It is precisely his transnationalism and simultaneous deep commitment to where he was situated—i.e., the US—that propelled him to start developing the work that would lead him to becoming one of the leading global intellectuals of the last fifty years. He started copiously traveling through the Global South and having conversations with religiously committed leaders across the world. Many times, those engagements took the form of physical travel. He traveled to places where global struggles against imperial and/or colonial dominations were taking place, such as the Philippines, Costa Rica, South Africa, and India. At other times, such engagements took place through a deep reading of voices beyond US borders where, in its imperial aims, the country had extended its “frontier.” But none of his encounters was more provocative than his creative dialogue with colleagues, visitors, and especially students first at Maryknoll, then at Florida State, Harvard, and ultimately Baylor University. Some of the students he mentored would face imprisonment after crossing the geopolitically created borders between the Koreas, others would face exile for interrupting capitalist extractivism in the African continent, and yet others would “disappear” for protesting dictatorships and servile democracies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Drawing from his knowledge of American society and the active exploration of transnational struggles, Dr. Ellis started to follow two mutually reinforcing paths: transnational liberation theology—many times, given imperial extensions and the invisibilization of other cosmologies, in a Christian framework—and the creation of a contemporary Jewish partner for dialogue with liberationist forces.

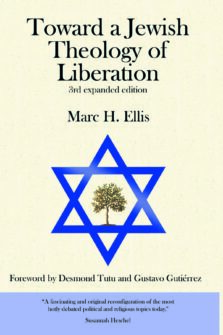

On the one hand, he contributed to the history of transnational liberation theology in a Christian framework. As was explored before, he trained hundreds of priests and nuns who would become community leaders against oppression in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. He also co-organized/edited an international meeting/volume to honor the work of Gustavo Gutierrez and played a key role in bringing the work of Palestinian liberation theologian Naim Ateek to Maryknoll (through Orbis Books). On the other hand, he started to develop a path to his landmark 1987 book Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation. Written for the first time a year before the first Intifada, he quickly updated it two years later to account for, understand, and support the revolutionary movement. Fifteen-years later he published the ultimate revised version with beautiful prefaces from Desmond Tutu and Gustavo Gutierrez, two leading religiously committed icons.

On the one hand, he contributed to the history of transnational liberation theology in a Christian framework. As was explored before, he trained hundreds of priests and nuns who would become community leaders against oppression in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. He also co-organized/edited an international meeting/volume to honor the work of Gustavo Gutierrez and played a key role in bringing the work of Palestinian liberation theologian Naim Ateek to Maryknoll (through Orbis Books). On the other hand, he started to develop a path to his landmark 1987 book Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation. Written for the first time a year before the first Intifada, he quickly updated it two years later to account for, understand, and support the revolutionary movement. Fifteen-years later he published the ultimate revised version with beautiful prefaces from Desmond Tutu and Gustavo Gutierrez, two leading religiously committed icons.

Both Tutu and Gutierrez, because of their struggle against oppression in Africa and Latin America, were accused of antisemitism by those who had perpetuated western discourses that made possible the annihilation of Jews (among other others) for centuries. Participants in this western discourse were replacing their old antisemitism in the Global South by creating false analogies between antizionism and antisemitism. This new strategy, that Dr. Ellis entitled the post-Holocaust ecumenical deal between Christian and Jewish establishments, was able to perpetuate the same culture of death that justified events such as the crusades, the inquisition, the conquest of the Americas, and the kidnapping and enslavement of human beings in Africa, under new rhetorical disguises and policies of censorship. One only need to read the deep words of Tutu and Gutierrez to learn not only how these leaders were able to redouble the commitment to their struggles through a renewed interest in Jewish histories of struggle, resistance and re-existance (including and perhaps especially Jewish activism on behalf of Palestinian political subjectivity and their right to live) that Dr. Ellis was presenting.

Expanding the Legacy

These two prefaces from Desmond Tutu and Gustavo Gutierrez offer an opening to the legacy that Dr. Ellis leaves with us. A legacy can be obvious, but its acknowledgement may not always be present. This is one of the fruitful explorations that Sara Roy, Dr. Ellis’s longstanding dialogue partner and leading scholar in the study of the long destruction of Gaza, and Atalia Omer—who illuminates, via her concept of the “critical caretaker,” current Jewish movements who are in solidarity with Palestine—engage in when they discuss the thinking, praxis, memories, and forgetfulness present in the explosive and promising social movements that are emerging in the public sphere today. The legacy of Dr. Ellis in American Jewish movements in solidarity with Palestine—in liberationist, decolonial, or other forms—is hard to overestimate. Yet, sometimes his name does not appear in these discussions. This may be due to more than one factor, one of which includes the changes in the way discourses are presented through time. But we cannot underestimate that one of the factors is the years of harassment, what today may be called gaslighting, he encountered. This came, first, from the establishment Jewish community now employing the same strategies of domination that Jews suffered from in the past. It came second, from reactionary Christian forces represented by, for example, the czar of political purity, the infamous Kenneth Starr, when he became president of Baylor. After Dr. Ellis had been recognized as the highest level of professorship (university professor) by the previous administration, the new conservative president started to formulate unfounded reasons to fire Dr. Ellis for political reasons. The new president would eventually fall in disgrace after a proven sexual assault scandal led to a demotion from his position. Yet Starr was able to selectively enforce outdated rules of a Southern Baptist university and force Dr. Ellis to take an early emeritus status. This generated a movement led by prophetic intellectual Cornel West and feminist scholar Rosemary Reuther to reinstate Dr. Ellis in his position.

The legacy of Dr. Ellis in American Jewish movements in solidarity with Palestine—in liberationist, decolonial, or other forms—is hard to overestimate. Yet, sometimes his name does not appear in these discussions.

The fact is that Dr. Ellis was never safe. And it is likely he never intended to seek out safety. Or, what is possible is that he was unable to find safety while at the same time remain committed to his convictions about Jewish responsibility toward oppressed people in general, and Palestinians in particular. The unholy alliance between “Constantinian” versions of Judaism and Christianity deserved his audacious and indefatigable critique. This engagement is particularly well developed in one of his books that I teach in several of my courses, Unholly Alliance: Religion and Atrocity in Our Time. During our dialogues I repeated to him several times that this was the book where he was able to offer his most comprehensive and brilliant contribution. But Dr. Ellis, an intellectual of strong opinions, refused to agree (or disagree) with my choice. It is not that he disliked this book, but he repeated to me time and time again that every contribution had a time and place and represented a step in the journey. For an author to choose one text over another without being able to predict who will be influenced by the writing was breaking the open potentialities of a text. He clarified, however, that potentialities were not always positive. They could include both generous people opening to further faithfulness with the prophetic and upset people launching new censorship policies and generating a new round of insecurities for scholars committed to social justice. But since the future was open and somewhat uncertain, he encouraged me to put aside strategic qualification and let every text run its course, for the better or the worse.

Taking advantage of his admission that a strategy that predicts certainty about one’s personal safety was an illusion, in late 2009 I insisted we still have pending his visit to Saskatoon. So he admitted that he could not ask me to do what he was not doing for himself (predicting insecurity or privileging safety over commitment). So ultimately he did come to the frozen little city of Saskatoon and, along with some partner organizations, we set up a lecture on a cold February evening in the middle of the week. What happened then was a testimony to what Dr. Ellis generated as a public intellectual beyond the sometimes narrow scholarly debates. Over 350 people attended an electrifying lecture in an overflown auditorium. Dr. Ellis’s faithfulness to justice brought out not only multiple university constituencies, but also many immigrant communities that were not necessarily part of the university (with their kids bringing new life to the event by running across the over-populated aisles of the auditorium).

A few days after the event, an authority of the institution, very satisfied with the turnout, told me that Dr. Ellis was able to bring to the university communities that “were hidden” (though I would say that they were “unseen”) in the small Canadian city. But this little story in Saskatoon is perhaps an excellent point of entry into his legacy. Dr. Ellis, with his faithfulness to justice, was able to open doors for expression, exposition, presence, and visibility to that which has been rejected. The role of the prophetic discourse, therefore, is to identify what is being negated, what has been silenced, and mobilize one’s identity from one’s positionality to claim the possibility of another possible world. It is only then that the prophetic remains alive. And this is how we can truly celebrate his life and commitment to those figures who can change history.