Thank you so much to my three generous colleagues, Kathleen Holscher, Niloofar Haeri, and Scott Appleby for their smart and thoughtful readings of my work, and to Atalia Omer and Joshua Lupo for creating this space for a conversation about Kindred Spirits. It is an honor to see how the book has stretched to speak to scholars working in fields adjacent to my own, and engaging with them is a welcome chance to think more explicitly about shared themes in our field—modernity, colonialism, and spirituality—that may have been undertheorized in the book. All of the thinkers have asked me to be a bit more explicit in my conceptual thinking. I’ll take this as an opportunity to deepen and clarify, and this is a most generous and welcome gift.

To begin with Scott Appleby’s essay, I must say that while reading it, I was seized with sudden flashbacks to my earliest semester teaching undergraduates fourteen years ago, when I would painstakingly try and define modernity for my students. I used Gustsavo Benievides’s Critical Terms essay, and would re-trace, whiteboard marker in my trembling hand, the various meanings of the Latin term modernus, and how it changed over time. More than a decade later now, I am in total agreement with Appleby that those debates seem to have fizzled out; I now rarely engage discussions about what we mean when we say “modernity.” Nonetheless I do appreciate Appleby’s point that I sometimes evoke the term more confusingly than maybe I should, sometimes descriptively, other times with a critical edge.

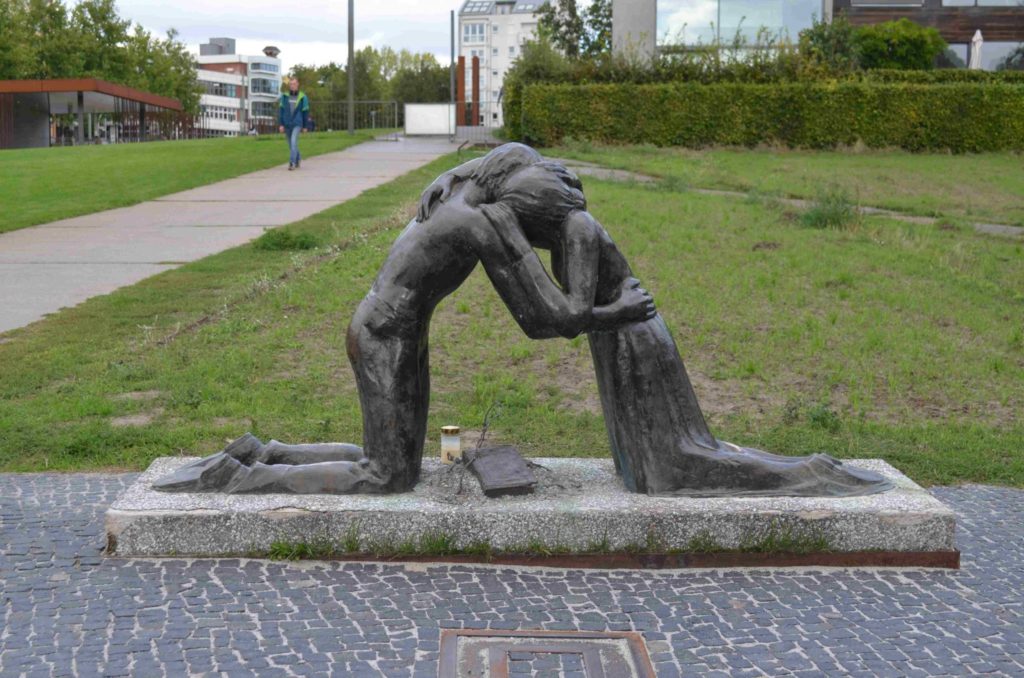

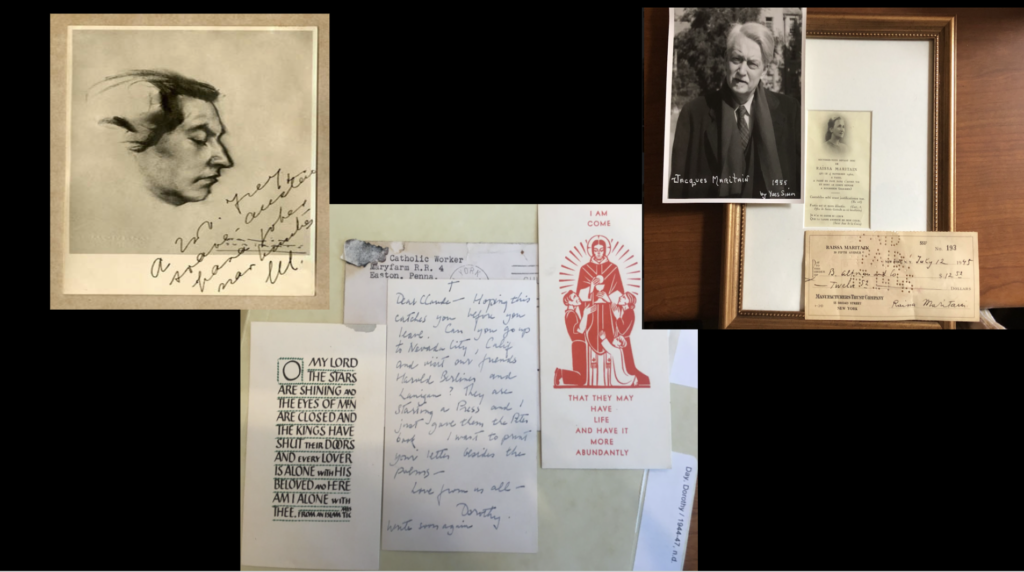

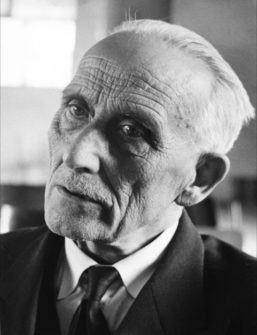

Grateful for the chance to clarify, I would say that my research relied on scholars of race and transatlantic modernity like Paul Gilroy to make an empirical point about the world that formed the protagonists of Kindred Spirits. Like those Gilroy writes about, some of the writers, poets, and activists in my book also experienced forced exile, fled violence, and lived rootless, vulnerable lives. This form of existence made friendship such an important anchor. This rootlessless also was something that writers like Claude McKay and Gabriela Mistral evoked in the art that give their works a wide, eclectic appeal and reach. This is a descriptive way of thinking about modernity: the global circuits carved from the violence of modernity—enslavement, wars, genocide—and the internationalist, eclectic art that came out of those same circuits. But the critical edge Appleby points to evokes the idea of the modern differently. One example here is where I suggest that male friendship offers an alternative to the dominant modes of male subjectivity that the modern world has on offer (think of the controlled, tough, independent “bottled up version of masculinity”). I do think that modernity is a swirl of cultures, fantasies, hopes, and imaginations, but in the west, despite this empirical mix, there are dominate cultural ideals that define what it means to be modern. I would say that one of these is that men should be emotionally restrained, untethered, and unencumbered. This suspicion of male intimacy was also central to colonial ideologies. Fantasies of male intimacy and sexuality in colonial countries were recoded as sexual sin, in need of Christian intervention and restraint. Or, as Marie Griffith and others have shown, these fantasies became the grounds of elaborate romanticization of sexual freedoms unburdened by western religious constraints. In either case, the Christian west was seen to be the space where men lived lives of independence and restraint when it came to intimacy. Though living in Europe and the United States and Christian, the men I describe in Kindred Spirits lived lives in radical disjunction to that dominant norm. And much of the ideas for this alternative did come from medieval monks (whose affective lives were more “uncorked,” to use Appleby’s words). Marie Magdeleine Davy wrote on the elaborate love expressed among Cistercian monks and Brian Patrick Maguire has written beautifully on medieval male friendship. These were models of alternative ways to embody masculinity taken up by people like Jacques Maritain and Louis Massignon. The affective, even queer way Maritain and Massignon carried themselves is “modern” in a sense because modernity creates space for the perpetuation of hegemonic norms as well as their subversion. I hope this clarifies the point I was trying to make in the book.

I will add here that when Appleby writes that I exhibited a “reluctance to stand back from the reporting of . . . richly detailed research” in some places, I felt he was peering into my soul a bit! The archival sources I used were so vast, so personal, so difficult to excavate, and the authors themselves were so prolific that it sometimes overwhelmed me. I feared I would never get out from under the sources. It is refreshing to now truly step back and bring these larger conceptual points into focus.

I do, however, depart from the conclusion that the “collective agency” of the men and women in my book “did not amount to much,” especially compared to “champions of the ressourcement such as Henri de Lubac and Marie-Dominique Chenu” and those like “Jacques Maritain….who interacted consistently with the Vatican.” I would emphasize here that the world I describe in Kindred Spirits includes Maritain and de Lubac, but by centering those more on the margins (like Davy, Massignon, McKay, Mistral) I move away from centers of Catholic power. White male priests like de Lubac or those White men loved by priests like Maritain were always invited into the halls of power. They looked like that power, and places like the Vatican and Notre Dame recognized them, applauded them, and welcomed them. Black writers like Claude McKay or the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral were illegible to the people in those places and operated in another sphere. As artists, McKay and Mistral worked at the level of imagination untethered to the levers of power in the 20th century. It is thus much harder to track what impact artists had on the cultural imagination than those invited to Geneva or Rome. But I would be reluctant to say they had no impact: McKay offered up in his poetry a completely new vision of what Black resistance could look like, and he is still read today. Mistral won the Nobel Prize for literature. Louis Massignon completely transformed the study of Islam for Catholics and inspired many of the Dominicans who remain prominent and influential scholars of Islam today. But this is a different kind of power. One of their impacts was in dispersing Catholic spirituality to places beyond the reach of the Vatican.

And I am so grateful to Katie Holscher who raises the important issue of coloniality and friendship, especially in U.S. contexts. I had a long section on the language of friendship in relationship to colonialism, associations exactly like those Holscher describes as the “Friends of the Indians” that “worked to dispossess Native peoples.” But this ended up being too far afield from the figures in my book. Still, I don’t want to let the figures in the book off the hook too easily. I especially related to Holscher’s evocations of Catholic confraternities that prayed for the living and the dead, a mix of spiritual and social bonds, in the language of love. Despite the softness of the language and the depth of the mysticism and the fact that it was Catholicism in a secular-Protestant country like the United States, the Catholic mystical imagination in communities like Friends of the Indian still worked to further colonial dynamics. She is exactly right on this point. Although the figures in my book tended to be critical of state power, there is a range in their approaches to this issue. Early in his career, for instance, Louis Massignon’s efforts at friendship with Muslims entailed a mix of prayer and pressure for conversion and we can see the colonial dynamics at work in the way Holscher describes. The most tragic figure in my book is that of the young Muslim scholar Muhammad abd Jalil, who converted to Islam under Massignon’s friendship and care, and was more or less disowned by his parents. Jalil spent time in a mental institution and had a very difficult life. Massignon’s ideas evolved over time, but the issue of friendship as a language that can soften the sound of colonialism is part of the story indeed. As I was writing, I had to remind myself that friendship is much like any other basic human endeavor: eating, walking, play, childbirth, swimming, loving, talking, fighting – something so basic and universal that it can be invested with an almost infinite range of meanings. But a story of the spirituality and politics of Catholic friendship with ties to Paris is one that should never exclude the ways in which this world has been entangled with colonialism. I appreciate this point and could have done more to stretch this. I imagine the possibility of a rich and needed volume on friendship in modern religion, where one would see friendship’s range across geographic, linguistic, and cultural contexts. When taken together, we could see what theoretical insights we could glean from a wide ranging set of data that reveals different stories friendship, spirituality, colonialism, and decolonialism in the modern world. This is so important with words like friendship, words that are warm, spiritual, and seemingly harmless. It is important to not simply show that there is always hegemony lurking there, but to open it up, explore it empirically, and be able to stretch our understanding of this important mode of human experience.

Shifting more from the political realm of structures and back into the inner domain, in terms of academic specialty, the scholarship of Niloofar Haeri, an anthropologist of Islam, is furthest from my own. It means a great deal that she connected to Kindred Spirits, and her own scholarship on friendship, kinship, prayer, and poetry has been an important influence on my thinking. Her essay here reminds me why. The language she uses keeps us tethered to the spiritual and the interior, even if it is always, in her hands, entangled with the external realms of language, culture, and embodiment. But nonetheless it has its own kind of integrity. She describes my work on friendship in this way: “There were beloved saints and some contemporaries whose being seemed to emanate a certain blessedness (very similar to the concept of those who are seen to have baraka in Muslim communities). That members of this group saw sacredness as not limited to the divine and to saints and prophets is one of the most interesting discussions in the book.” Reading Haeri I am forced to confront my own habits. For example, I often emphasize the political nature of experiments and efforts of the friendship networks I describe. But for them, it was how friends embodied some part of the supernatural that was most fundamental. The beautiful phrase “to emanate a certain blessedness” (baraka) inspires in me a desire to learn more about the idea in Muslim communities.

Thank you again so much to Katie, Scott, and Niloofar for these incredibly helpful readings that pushed me at last to stand back and clarify my conceptual thinking. I find myself now looking to future projects as a chance to be more explicit in my analysis of how experiments in Catholic spirituality worked to advance or undermine the French colonial project – I was too subtle on that point and need to tackle it more directly. I am also reminded too of the need for further elaboration of second, rather distinctive impulse to consider the experiential aspects of religion, the piety and devotion that requires a somewhat different set of analytic tools. In future projects I hope to go further with both of those rather distinct set of questions, both of which I find fascinating and can tackle more explicitly head on. Thank you again to my generous readers and colleagues.

Modernity, it would seem,

Modernity, it would seem,