Emmanuel Katongole’s brilliant new book features significant African individuals and movements that disrupt the conceptual dichotomies imposed by “modernity”: politics/religion, public/private, secular/religious, state/church, and so on. By examining such examples, Katongole not only sketches the contours of a new type of politics in Africa, but implies that this model might be of relevance to Christians and others in the West as well. The last general conclusion that Katongole draws in the book is that “the African church is a unique gift to world Christianity” (264). Given his blurring of lines between religion and politics, it may be that Katongole thinks Africa has something to say to the West about the viability of its own structures of modernity.

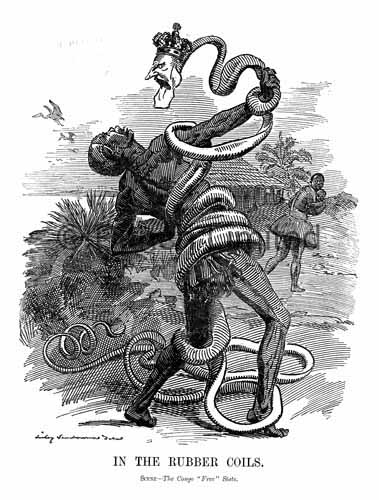

The dominant narrative suggests that the West has successfully modernized, and thus the debate over Africa revolves around whether or not Africa must follow the West’s model or seek its own indigenous path toward success. An example of the former opinion is Catholic political scientist Paul Gifford’s 2015 book Christianity, Development and Modernity in Africa. Gifford traces the root of Africa’s problems to its neo-patrimonial system of clientelism, which he contrasts with the West’s rational-legal form of governance. Gifford acknowledges that colonialism was problematic, but identifies the “dysfunctional neo-patrimonial political culture that is primarily responsible for Africa’s present plight.”[i] Unlike Katongole, Gifford does not explore the link between colonialism and neo-patrimonialism, and so he treats neo-patrimonialism as cause rather than effect. The solution, according to Gifford, is Western-style modernity, and he dismisses the idea that there are multiple competing modernities, just as he dismisses the idea of multiple scientific methods. “The challenge is surely for Nigeria, Congo, Zimbabwe etc. to move themselves ‘towards Denmark’. Their route will not be the same route that Denmark took, but the destination is the same.”[ii] Denmark represents the ideal of good nation-state governance, an impersonal provider of goods and services defined by public law. According to Gifford, “Denmark is the destination to which Africa’s Catholic Church in general is nudging Africa.”[iii]

Katongole clearly would disagree with both Gifford’s diagnosis and his cure. In Born from Lament, Katongole extends his argument in The Sacrifice of Africa that neo-patrimonial corruption and violence are essentially a continuation of colonial politics; the implosion of African states happens not despite but because of the West’s best efforts. He does not think the cure, therefore, is simply more Western nation-state politics, though presumably he would applaud Gifford’s calls for more transparent and honest government. But neither does Katongole think that the cure is simply the rejection of the West in favor of indigenous African culture. He has elsewhere critiqued the “inculturation” model, and here he criticizes the traditional African cosmology that makes a weak and suffering God hard to grasp (120). The choice for Katongole is not simply the choice between Africa and the West, in part because their histories have been so densely intertwined. More determinately, though, Katongole sees his exemplars in the book as offering something really new for Africa. The cure for Africa’s problems does indeed need to come from outside of Africa, but not from Denmark. It needs to come from God. Re-creation requires the Creator, which is precisely why hope differs from resilience, optimism, a can-do spirit, or well-intentioned attempts to fix the world.

While the achievements of Denmark in providing security for its people deserve admiration, Katongole wants a politics that aims higher. The problem with Denmark as destination goes beyond the fact that it is a foreign, non-indigenous cure for Africa. The problem is that it excludes the kind of eschatology that Katongole thinks provides real hope for Africa. Denmark (as an ideal type, not necessarily in empirical reality) represents the “end of history,” a state of stasis in which the army, police, and state bureaucracy keep order while consumers’ desires are addressed by the market. God is unnecessary. There are no more ruptures in history, because everyone’s needs are met, and everyone’s desires are entertained. There is no need to care for one another, because the state provides. Suffering has been erased, so there is no basis for hope. People are free to desire anything but hope for nothing. The whole drama of sin, lament, redemption, and reconciliation is necessary only for the unlucky many who live in poor countries. Again, “Denmark” here indicates not so much a real place but an aspiration, and the aspiration is not simply wrong. Alleviating material suffering is of course a worthy goal, one that Katongole wholly embraces. But he aspires to something higher, a true reconciliation of all in God.

Gifford predicts that the church will wither in Africa as it has in Denmark precisely to the extent that Africa is successful in following the Danish model. He criticizes the Catholic Church in Africa (“Oxfam with Incense”) for neglecting its “religious” mission while concentrating on “secular” services like health care, education, and poverty alleviation. When the state steps in to provide these services, the church will surely shrink.[iv] Katongole, as I read him, is trying to address this problem by refusing to choose between “religion” on the one hand and “secular” development projects on the other. In so doing he is refusing one of the fundamental building blocks of modernity, the religious/secular binary. What he hopes for Africa is a society that lives from the hand of God, who opens up fresh and previously undreamt possibilities. Katongole hopes for a politics that is not fully captured by the nation-state imagination of order through coercion. He hopes for a practice of peace that conforms people to the nonviolence of a God who chooses to suffer rather than resort to violence. Katongole hopes for an economy of gratuity that has more to offer than the entertainment of desire in the market.

Although his primary concern in this book is Africa, Katongole seems to think that Africa has gifts to offer us in the West. Although Katongole uses Douglas John Hall’s analysis of the West’s inability to lament to support his analysis of Africa, the two analyses are intertwined. Hall clearly implies that the West’s inability to face suffering, and its aspirations toward limitless accumulation and freedom, have been murder on the rest of the world through colonization, slavery, and economic exploitation. “’The whole world,’ Hall writes, ‘suffers today because its most powerful societies desperately retain expectations that can no longer stand the test of experience’” (181). But this pathology is not just a problem for Africa; it is a problem for the West. The West’s inability to think of hope as anything other than technical progress in the avoidance of suffering leads to the kind of desperation to which Hall refers. Christianity in the West has failed to be anything other than a purveyor of shallow optimism. The African Christian exemplars that Katongole portrays, on the other hand, bear witness to a God that absorbs suffering and transforms it, rather than trying to avoid it or shift it onto someone else. Katongole, it seems to me, is raising the question of a politics of solidarity for both Africa and the West. What would it look like to have a body politic in which “if one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it” (I Cor. 12:26)?

[i] Paul Gifford, Christianity, Development and Modernity in Africa (London: Hurst, 2015), 10.

[ii] Ibid., 154.

[iii] Ibid., 155.

[iv] Ibid., 159-61.