I am a Palestinian Hebrew-Israelite (or simply “Israelite” for short).

By the foregoing confession, I do not mean that one identity or the other is ontologically isolated from the other. Nor do I mean that one is embedded in the other, or even that they are qualifications of each other. For I am also a rabbi who works with gender-nonconforming Jewish teens. None of these qualities inform my Israelite identity. They are my Israelite identity. The radicality of this assertion has been the source of much confusion in the media about who Hebrew-Israelites are. And in light of recent years’ focus on Jewish activism, perhaps it is time for some clarifications.

The Paradox of Faux Jewish Solidarity

My Jewish story begins with the Middle Passage as much as it does with my grandparents’ flight from Palestine. Because slavery, sex, trafficking and diaspora are seminal to my existence, al-Nakba, for example, can never for me be a singular 20th century event. It is rather the entire constellation of violent processes that made modern Jewish coloniality, as well as that singular catastrophe, possible. This is why I have for many years been publicly critical of using allegories and analogies to promote cross-communal solidarity. The problem with their use is not only that they can provoke collective traumas while reasserting Jewish metanarratives that demand my community’s phenomenological disappearance. It is also that they often betray a deep-seated desire for us as Jews to construct mirrors of ourselves without a background context through which to assess the self-images we promote. For example, the “BIJOC” label (Black, Indigenous, Jews of color), in both genealogy and referential axis, is not for me an inclusive signification. In fact, in many ways the acronym provokes in me a cultural memory of rape and sexual violence, a common theme when it comes to the history of how identities are superimposed on people from without. My community, on the other hand, is uniquely and unparsimoniously self-referential, hence the term “Hebrew-Israelite”—that is, people of Israel who by nature “transcend.” This description (as opposed to the racist labels “BlackIsraelite” and/or “BlackHebrew Israelite”) is important for understanding the many anticolonial (not decolonial) complexities found in the global South’s Hebrew-related communities. These peoples may include all future descendants of earthlings, for transcendence to us means moving beyond religion, culture, nationality, humankind, and all other significations rooted in coloniality.

The problem of a jim-crow Torah arises when Jewish affirmations of holiness simultaneously embrace particularity and universality by evoking a cultural memory of alliances with “outsiders,” all while ignoring the intracommunal effects of intergenerational trauma within the Jewish community itself.

Without sounding too dismissive, it seems to me that appeals to Jewish relational analogies, even if drawn upon to promote cross-communal interest-convergences, can powerfully reinflict trauma, particularly when such appeals are made without acknowledging some obvious historical contexts that make them problematic. There is a gadflyish paradox in Jewish attempts to mitigate the violent historical effects of Jewish coloniality through a quest for justice-oriented solidarity with BIJOC and/or other peoples of color. Whether in Israel, Palestine, or diaspora, Jewish colonialism was a catastrophe. It led to the proliferation of Jewish races and imposed a legitimation crisis on Jewish activism: How can Jews claim solidarity with people of color while rejecting those who are Jews because they are people of color? What kind of solidarity is this? In the Hebrew-Israelite community’s case, it can be nothing less than a faux solidarity precisely because the catastrophe (or al-Nakba) of human trafficking that attended African American origins are what have provided us with the whiteness and privilege of many Jews that make such Jewish “solidarity” possible.

Hebrew-Israelites and the Lesson of Community-Building

We Israelites learned generations ago that attempts to evade the inevitable cultural integration resulting from modern colonial violence prove themselves to be futile in the end. All communities are, by definition, in the constant process of growing and renegotiating boundaries. But in the case of Hebrew-Israelites, our intra-communal debates over the margins of identity have been used to not only depict us as kooks in popular media, they’ve also been used by Jewish communities themselves, including self-espoused BIJOC groups, to justify the policing of Jewish existential legitimation. It is my position, however, that such policing has consistently ignored the necessary encounter with Others attending our experiences as people who embrace a variety of genealogies as “Israel.” These are not allegories nor analogies nor metaphors “of” Israel, but rather Israel as such. Even when acknowledging the nodes of incommensurability between Jewish self-determination and other liberation movements such as that embraced by Hebrew-Israelites, the process of community-building with Others is inevitably aided and abetted. Al-Nakba occurred as a result of efforts to ignore this process. One such effort was the invention of new speech-acts that segregated Jews who are “in” from those who are “out,” irrespective of whether those victims of segregation understood themselves as such through those speech-acts—especially when the mixtures and creolizations inherent in Jewish coloniality made this segregation untenable. While portraying the segregationist as like an “evil sower” from a New Testament parable, Prophet William S. Crowdy describes this very dilemma in one of his sermons:

Evil sowers are those that invent[ed] separation between one blood, for the scriptures said that the Lord out of one blood created all to dwell upon the face of the earth, but the evil sower says, ‘No, we shall not be together, but we shall have jim-crow cars, jim-crow boat lines, jim-crow railways, jim-crow boarding houses, jim-crow churches, jim-crow barber shops, and jim-crow laws for the Jews to live under’ (175–76).

By focusing on the invention of “separation between one blood,” Crowdy appealed to a shared human dimension of Jewish existence. Unlike contemporary Jewish solidarity movements, he was not referring to an analogy, metaphor, or allegory to establish and/or reinscribe ties between Black and Jewish communities. For him, such kinds of discursive linkages were insufficient to address what centuries of human trafficking engendered. He was instead pointing out the historical and conceptual problem that racial segregation poses for Jews who wish to live beyond the confines of a jim-crow Torah (or a jim-crow law for Jews).

Eliminating Misunderstandings

The problem of a jim-crow Torah arises when Jewish affirmations of holiness simultaneously embrace particularity and universality by evoking a cultural memory of alliances with “outsiders,” all while ignoring the intracommunal effects of intergenerational trauma within the Jewish community itself. Existential ruptures of this kind always feed off the false ideals of ontologically isolated communities. For example, consider the malignant and exoticist narratives promoted about Hebrew Israelites in the popular media. According to these narratives, Hebrew-Israelites are members of militant cults that embrace a racist kind of heretical, and at times criminal, counter-narrative against normal Jewish traditions (including BIJOC traditions). But this narrative is largely false, and it is false to such a degree that one is tempted to believe that such an account of my community’s history is built more on spite, suspicion and racism than historical accuracy. When members of early postbellum Hebrew-Israelite communities were asked by outsiders where our religious practices came from, there was one historical explanation that was consistently dismissed over and over again: Jewish slavery and sex trafficking.[1] The memories of such events are alive and well in Hebrew communities across the Americas. Yet those narratives are ignored, and exoticist ones are popularized instead, particularly the long and racist tradition of portraying Black people as violent, corrupt, and prone to criminality. And although this aspect of Jewish culture and religion has been intentionally and conveniently ignored by some preeminent scholars of American Jewish history, Hebrew-Israelite communities continue to bear, in the words of Caroline Randall Williams, “rape colored skin.”

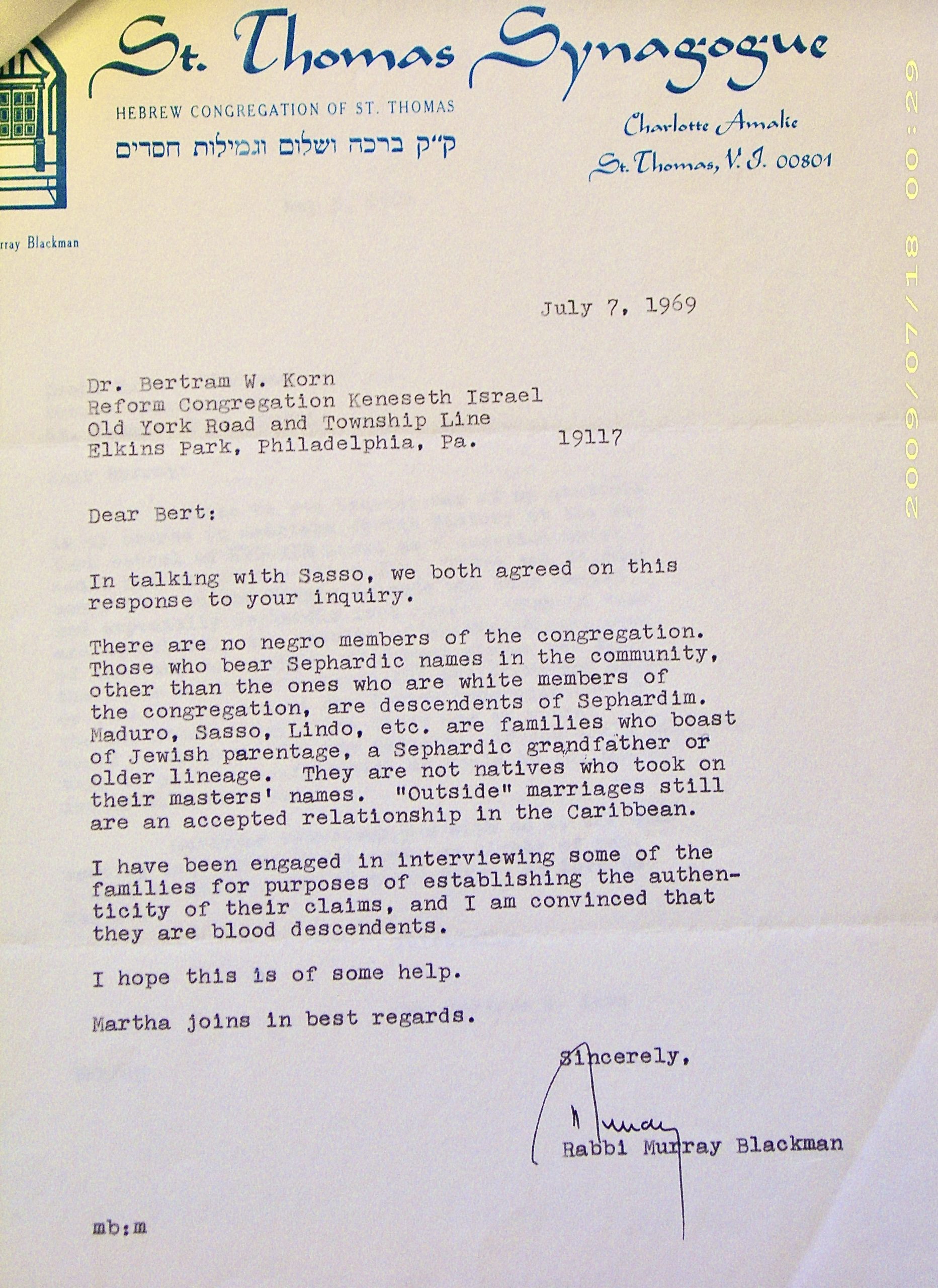

Rabbi Bertram Korn sought to argue that no black Jews existed outside of synagogues after slavery’s abolition. But he fell into dispute with Caribbean rabbis who insisted otherwise. In these letters, multiple authors are clear that biological descent is responsible for the existence of many black and mulatto Hebrews in Central and South America and the Caribbean–even though such people of Jewish descent were estranged from synagogue life. Photo Credit: Author’s photographs used with permission from the Jacob Rader Marcus Center at the American Jewish Archives.

Much like Vodou, Conjure, and Santeria, Hebrew-Israelite practices have been criticized because they are more concerned with the historical effects of racism, colonialism, and anti-Black trauma than they are with doctrinal purity, monotheistic orthodoxy, and especially rabbinic norms of Jewish identity construction. People in my community have often been marginalized (and at times blacklisted) for emphasizing and making too much of these facets of American Jewish history. However, I believe such criticisms are misplaced. Convenient historical fictions quite often infect conversations between victims and beneficiaries of atrocities. The notion that Palestinians “willingly” abandoned their homes during al-Nakba is one such example. The notion that Hebrew-Israelite communities didn’t exist before the 1890’s is another.[2] Our communities are maligned because we are inherently diverse and do not allow class divisions and educational privilege to regulate religious discourse in the form of a single hierarchy. As a result, detractors use the more provocative beliefs of some members of our community to slander the reputation of all. Yet the fact that our community embraces large contingencies of humanity—from rabbinic Jews to Biafran nationalists—should be seen as a strength (and perhaps a lesson) in Jewish struggles to work for social justice. The insights of prophetic justice are assumed to be available to all Israelite persons—to the criminal as well as the law-abiding, the illiterate as well as the scholar, and the poor as well as the financially secure. We already assume that human communities are interdependent and connected in forms of solidarity, whether made explicit or not. And it is for this reason that discourses about Jewish solidarity can be alienating: the social deaths of enslaved Hebrew-Israelites, deaths provoked by the trauma of human trafficking, deaths which engendered global understandings of “Israel,” deaths continually and presently ridiculed for revealing “Israel” to be composed of many cultures and peoples, including those presumed to not be Jewish or Hebrew at all—these very same deaths are reinscribed in theodicean clouds of misunderstanding when a muted history of sexual violence informs the coherence of Jewish solidarity movements signified by acronyms such as BIJOC.

Moving Forward Together

By criticizing the move to establish coalitional politics with a focus on activism, it is not my intention to romanticize Hebrew-Israelites or Palestinians. My experience has been that both groups exhibit their own forms of the very same problems I am outlining here for Jewish solidarity movements. Jewish and Muslim rape cultures existed wherever slavery was found in the colonial period. The violent practice has existed for millenia, and although I believe discussions on how to move forward on questions of justice are important, I also believe that in the desire to demonstrate that Jews are on the right side of history, the (white and non-white) Jewish community’s problems with racism are often ignored. Addressing these problems can sometimes be far more effective at alleviating injustice than creating solidarity movements with Other communities. This is because various “in group” avenues, due to being more immediately relevant to the social tasks at hand, can more powerfully employ Jewish communal resources as such to both confess and work against the wrongness of being rooted in Jewish coloniality. Religious reparations to Hebrew-Israelite communities who have suffered damages from white Jewish racial and sexual assault is only one such avenue. But there are many others, and many of them can remind us that Jewish existence itself is often refracted in ways that make cross-communal solidarity movements unnecessary and at times counter-productive. It is quite possible that the coalition one seeks to promote is the very means by which the oppression you fight becomes resurrected.

Jewish and Muslim rape cultures existed wherever slavery was found in the colonial period. The violent practice has existed for millenia, and although I believe discussions on how to move forward on questions of justice are important, I also believe that in the desire to demonstrate that Jews are on the right side of history, the (white and non-white) Jewish community’s problems with racism are often ignored.

In conclusion, I do not believe that what I am proposing here is difficult. The upshot of my argument has to do with maintaining a basic appreciation, respect, and historical awareness of the people we claim to be allying ourselves with. A profound sense of existential humility is required when one commits oneself to the project of human freedom. All too often, Jews of Color (as well as their white Jewish advocates) lack such humility. Neither Hebrew-Israelites, Palestinians, nor BIJOC are exceptions to this note of caution. For some of us, standing up for the rights of Others and demanding that they be invited to participate in proactive coalitions that fight for social justice are important aspects of our spirituality. For Others, the means by which this happens recycles entrenched forms of marginalization that have violent roots as their genesis. But regardless of who one claims to be, if such a person is oppressed, then trust capital from the beneficiaries of one’s oppression is nearly always earned, not given away willy-nilly. One earns another’s trust by being reliably honest and transparent. Yet no matter how sincere one’s efforts to be in solidarity, silence about one’s role in the Other’s oppression will never reflect that kind of honesty. If Others’ “allies” in the fight for justice cannot transcend a dishonest relationship with the history of such oppression, then those Others will always have reason to avoid that solidarity movement like the plague.

[1] There are many references to this phenomenon in the works of scholars such as Jonathan Schorsch, Saul Friedman, Jose Malcioln, Judah Cohen, as well as early 20th century articles on “Negro Jews” in Harlem from the New York Amsterdam News. To begin the investigation of this issue, please see Bertram Korn letters to Caribbean rabbis and vice versa. Folder 12: “Blacks: Jewish Blacks in the Caribbean,” Box 3, (MS-99) Bertram W. Korn Papers, Rabbis, Major Manuscript Collections, the American Jewish Archives, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, Ohio.

[2] As Jacob Dorman has shown, such ideas are still popular, over 100 years after they were first proposed and dismissed. See page 62 of Dorman’s article.

*”It was surprising to me to see some negresses in their synagogue, who prayed with true devotion, but without the exaggerations that are usually characteristic of blacks… I heard that they were formerly slaves of the families in which they still live; when slavery was abolished in New York State, they voluntarily remained with the rulership they had loved, whose faith they also accepted.” Translated via Google translate from Israelitische Volks-Bibliothek. V: Deutsch-Amerikanische Skizzen fur Judische Auswanderer und Nichtauswander (Leipzig: Oskar Leiner, 1857), 60.

Thank you for this insight rabbi. I am neither black, nor Jewish. I am a white atheist that had been raised Southern Baptist. It was enlightening to read about the many different “Jewish” communities and schools of thought. I appreciated your emphasis generational trauma as it results from trafficking and understanding the stigma others place on survivors and descendants. Thank you for explaining situations when other Jews have found someone too “other” to be a Jew like them. Your call for internal solidarity is well written and I agree that it will have a positive impact on the community’s ability to work positively with other people groups. Wishing you well, Mike Parsley