William Cavanaugh (WC): Yaacov, your book, To Be a Jewish State: Zionism as the New Judaism, could hardly be more timely. You examine some of the tensions between Judaism and the state of Israel at a time when there is a tendency to conflate antisemitism with criticism of Israel, and you offer more general lessons on nationalism at a time when it is resurgent. Can you summarize the argument of your book?

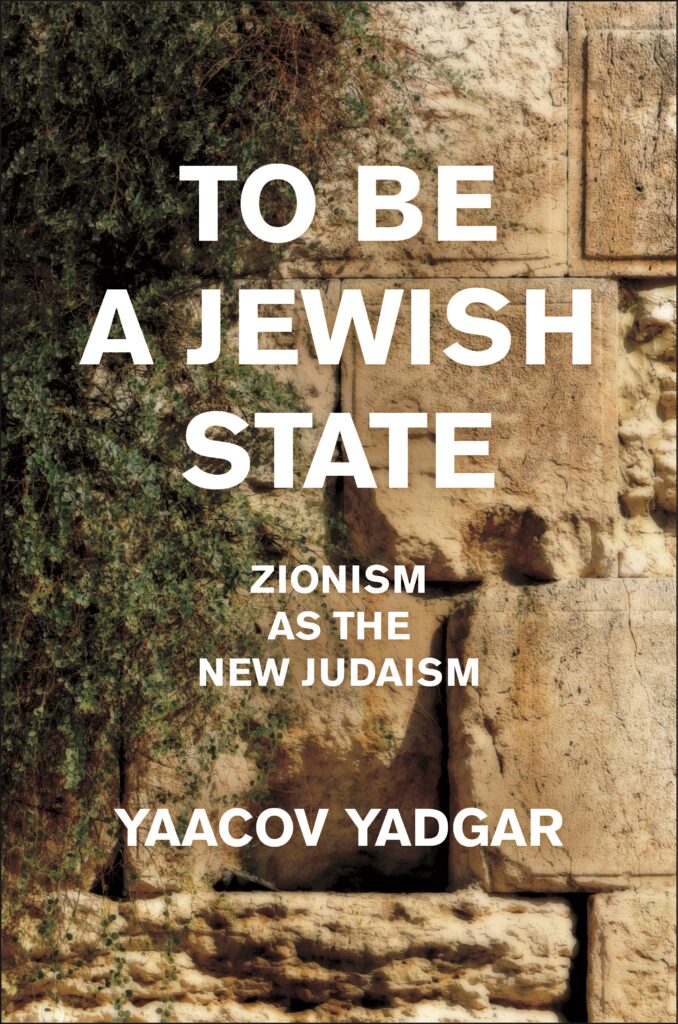

William Cavanaugh (WC): Yaacov, your book, To Be a Jewish State: Zionism as the New Judaism, could hardly be more timely. You examine some of the tensions between Judaism and the state of Israel at a time when there is a tendency to conflate antisemitism with criticism of Israel, and you offer more general lessons on nationalism at a time when it is resurgent. Can you summarize the argument of your book?

Yaacov Yadgar (YY): Well, the shorter version of my argument is that to understand Israel we must take a critical account of Zionism’s (and, following its cue, Israeli political culture’s) relation to Judaism. Contrary to some prevalent, naïve assumptions (for example, that Zionism is a simple “secularization” of Judaism; or, alternatively, that Zionism is a modern development and even culmination of Jewish “religion”), this relation is far from straightforward. Zionism simultaneously appropriates and negates Jewish history, tradition, and identity. Reading Jewish history and tradition through a modern-nation-statist frame of reference, Zionist ideology has sought to rewrite the very meaning of Jewishness through its politicization or “nationalization”—that is to say, “fitting” or binding Jewish identity and Judaism itself—to the nation-statist imperative. The dual act of appropriation and negation has obviously created tensions and paradoxes that determine, to my mind, Israeli politics and Jewish politics more widely.

It is important to note that with all of its “Jewish” idiosyncrasies, the Israeli, Zionist case is far from being an outlier. This is merely a local, specific rendition of the playing out of some of the founding paradoxes of the so called “secular,” liberal modernity’s relation to its “religious” past. Or, more specifically—to use your own framing, this time—it is about the encounter between “the splendid idolatry of nationalism” and its traditional past.

It is interesting to reflect on the matter of “timeliness” or “topicality” of the book and its argument. The matters discussed in the book—from the meaning of Israel’s “Jewish identity,” through Zionsim’s relation to Judaism, the problematic implications of the “sanctification” of the state, and to the problem of the Israeli past—are foundational, and even if they have been ignored (or, I suspect, actively denied) in the past, they are not novel, nor are they necessarily tied to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict (rather, they function as the backdrop to this conflict, and in many ways determine the Israeli course of action in it). It is indeed a devastatingly sad fact that it is only in the context of such horrific violence that people both in the Jewish world and outside of it take a more serious note of these foundational issues.

(WC): So you are arguing that the distortion of traditional faiths by nation-statism is a more general phenomenon, but the warping of Judaism by Zionism is a particularly interesting case study of that broader phenomenon. Some Christian theologians have been trying to root out supersessionism from Christian views of Judaism, but you argue that there is also a type of supersessionism in which Zionism replaces Judaism, and that such nation-statism ultimately has Christian roots. Can you say more about the distorting effects of nation-statism on both Judaism and Christianity?

(YY): Nation-statism usurps tradition. The modern state must “deal” with the traditions carried and practiced by those in the name of which the state claims sovereignty. These traditions are too powerful, too constitutive of sociopolitical reality, to ignore; they are what makes the people who they are, and if the state is to succeed in making these people its loyal subjects, it must address their traditions. What we have come to call “nation building” thus means, among other things, adopting, appropriating, reinterpreting, rewriting, negating, etc. those traditions that preceded the state, and which often continue to live alongside the dominant “national tradition,” the tradition of the nation-state.

The issue is, of course, that what motivates and guides the state in its relation with these traditions is not the truth entailed in them, but the interest of the state. Moreover, it is not hard to see that often the interest of the state explicitly contravenes this traditional truth. Yet the state speaks as if it is the ultimate, most authentic embodiment of the essence of these traditions. Clearly, this entails a distortion of tradition, which preceded not only the modern state itself, but the very epistemology that gave birth to this configuration of power in the first place.

I find the notion of supersessionism helpful in understanding this relation between the state and the traditions that preceded it—in the case of my study, we call these traditions “Judaism,” which confusingly suggests a unified, homogeneous even, notion of tradition; it is rather heterogeneous and diverse—for two reasons. First, and primarily, supersessionism neatly captures the dual act of appropriating and negating. It is an act of capturing—or usurping—authenticity itself. You see it clearly in the case of Zionists ideologues, who speak for Jewish nationalism, and explicitly set out to eradicate what they would call Jewish “religion” in the name of allegedly salvaging the true meaning of Jewishness, which they would then seek to enshrine in a new national political theology or relegia of worshiping the nation-state. Second, employing the theological concept of supersessionism to what is usually discussed as a matter of allegedly secular politics helps us see much more clearly, I believe, the theopolitical play at hand. This should, of course, be trivial to anyone who has read your work, Bill. Employing the concept of supersessionism to analyze the relation between the state and traditions that preceded it helps us, I think, see the idolatrous nature of the act of nation-statist theopolitics.

(WC): Your critique here and in your book of Zionist ideologues who set out to eradicate Jewish “religion” seems to apply to “secular” Zionists, but you also critique “religious” Zionists who seek to sacralize originally “secular” things like Jerusalem Day. You show in fascinating detail this dual dynamic of redemption politics in Israel, both the secularization of the sacred and the sacralization of the secular. Can you say something about what remains once you have shown the dangers and inadequacies of both religious and secular Zionists? What is your positive vision about how to practice Judaism in Israel?

(YY): The construction of any positive vision for the practice and meaning of Jewish tradition(s) in Israel and outside of it must be—pardon the tautology—a traditional endeavor: that is to say, it must come out of a debate from within the tradition on the meaning of tradition. This means, among other things, that any such positive construction would have to be the outcome of a collective effort, not a product of a single author’s program or critique. It also means that such constructions cannot be directed by an identity-politics-driven type of intervention, where one’s accident of birth (that is, one’s being “a Jew,” in our case) allegedly gives one the prerogative to define the meaning of the tradition.

My humble contribution to such a collective effort would be to explicate the enormous—but necessary, I would say—challenge of allowing the traditional discussion to be held outside of the confines of the nation-statist imperative. We live in a world in which the nation-statist imperative is taken to be a matter of the natural order of the world, and much of what goes on as Judaism is bound to the altar of the state. Frustratingly, this is also true of much of what presents itself as a Jewish critique of Zionism and Israel—many of these critiques, too, remain bound to the state, even if they do so negatively, by way of negating aspects of it.

I offer in the book the case of Leon Roth as a wonderfully complex and nuanced iteration of an attempt to present a positively Jewish critique of Israeli politics. Roth’s critique of Zionist and Israeli politics, or actions, was an intimate critique—he himself was, up to a point, an active agent in the Zionist enterprise. And more importantly, this critique was the product of Roth’s deep, rich engagement with Jewish religion, with the teaching (the literal meaning of torah) that we call Judaism. He exemplifies the power, clarity, and depth of such a Jewish position. Yet he himself, I suspect, was also unable to break free of the nation-statist imperative.

Granted, this is an enormous, maybe simply impossible task. It is easy to be drawn to pessimism and even quietism in face of the now forcefully resurgent power of the nation-state. But I like to draw inspiration from the very last lines in the late Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue: “What matters at this stage”, he writes, “is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us” (263). The same goes for Jewish tradition.

(WC): I was struck by your appeal to MacIntyre and by your appeal to a certain kind of virtuous “tribalism” opposed to statism at the end of your book. I don’t expect a blueprint for the future of Jewish tradition in Israel, but could you give an example or two of what such a virtuous tribalism does or can look like?

(YY): Probably the most obvious example of what a “tribal” (or, if the term is too charged and misused: a “confederational”) approach to Jewish collectivity can yield is its devastating blow to the nationalist construction of the “Jew. vs. Arab” duality, opening venues for overcoming what seems to be the defining conflict of the Middle East in the past century. It is almost trivial to note that Jewish nationalism, in its Zionist construction, pitches “Jew” against “Arab” as mutually oppositional identities, ultimate enemies, the essential “us” and “not us.” This nationalism, in other words, has rendered the “Arab Jew” an oxymoronic construction, not only dismissing some of the most insightful, rich, and innovative historical expressions of Judaism itself, but also rendering people’s lived experiences an impossibility. A reaffirmation of Jewish diversity would, among other things, allow for these identities to cohabitate, and potentially to create coalitions and pacts that “criss cross” the nationally imposed binaries.

On a more substantial level, I think it also goes without saying that the diversity and heterogeneity of the human kind is in itself a virtue. One could make a strong argument that this exactly is the message of the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. Without pretense to speak theologically, I think it is a given that the multiplicity of human languages, traditions, practices, etc. diversify and enrich our ways of being in the world; this multiplicity is a good thing. We are justifiably worried about the disappearance of languages, as these are not mere tools of communications, but whole ways of seeing the world and being in it that are lost with the death of these languages. It is an incredibly sad fact of Jewish history that the State of Israel has been the burial ground of so many Jewish languages, lived and carried by communities throughout the world for centuries, only to be forcefully replaced by modern, Israeli Hebrew in Israel as part of the “nation building” project. The same goes for Jewish tradition itself: what we know as Judaism is historically diverse and heterogeneous, and this very diversity has been celebrated in the past as part of the essence of Jewish tradition. To lose this richness is, simply, too dear a price to pay.