In recent years, the plight of Middle Eastern Christians in the wake of both the Arab Spring and the rise of ISIS has been a central focus of Western religiopolitical interest. Western Christians have depicted Middle Eastern Christians as persecuted peoples and martyred co-religionists, viewing their plight as an extension of a broader global trend of anti-Christian hate. In his latest book, Mitri Raheb offers a historical account and contemporary analysis of the representation of Middle Eastern Christians as victims. In doing so, he also advocates for a refocus on their agency and resilience. From the perspective of a Palestinian Christian theologian, The Politics of Persecution: Middle Eastern Christians in an Age of Empires offers a decolonial and grounded view of power as it is experienced by Middle Eastern Christians. In opposition to portrayals of Christian death and ruin in the Middle East, Raheb lays the foundation for a new way of looking at Christian communities in the region—not as merely objects of analysis, but as actors telling their own stories.

In this post, I weave together the findings in Raheb’s book with my own research and forthcoming book on the transnational religiopolitical translations of Coptic Christian persecution between Egypt and the United States. Raheb argues that Christian persecution in the Middle East is a construction of the West and that the idea of persecution says more about the West than it does about Middle Eastern Christians (143). I partially agree with Raheb that broader structures of imperial power have shaped modern Christian identity in the Middle East. Yet, Raheb’s text does not elaborate on the more intimate, ethnographic layering of these structures within the everyday life of different Christian communities in the region and in their diasporas around the world. Such communities experience their Christianity in diverse ways and contend with unique transnational politics of migration in and out of the region.

Mitri Raheb offers a historical account and contemporary analysis of the representation of Middle Eastern Christians as victims. In doing so, he also advocates for a refocus on their agency and resilience.

Between 2016–2021, I conducted multi-sited ethnographic work among recent Coptic migrants: first-, second-, and third-generation American Copts and clergy members moving transnationally between Egypt (primarily the village of Bahjura), Naj Hammadi, Upper Egypt, and the United States (primarily Jersey City, New Jersey). Shuttling back and forth across these sites of migration, I examine the everyday practices and processes that shape transnational Coptic communal formation and belonging as it interfaces with the tension between their minority status in Egypt and their racial-religious placement within an American Christian conservative landscape. My interlocutors related to one another through their religious tradition as well as through their politicized transnational minority condition. As I argue, their struggle to grapple with their minoritization, modulated as it is between Egypt and the United States, poses the question of political praxis and interpellation in a broader geopolitical framework of international religious freedom and counter-terrorism.

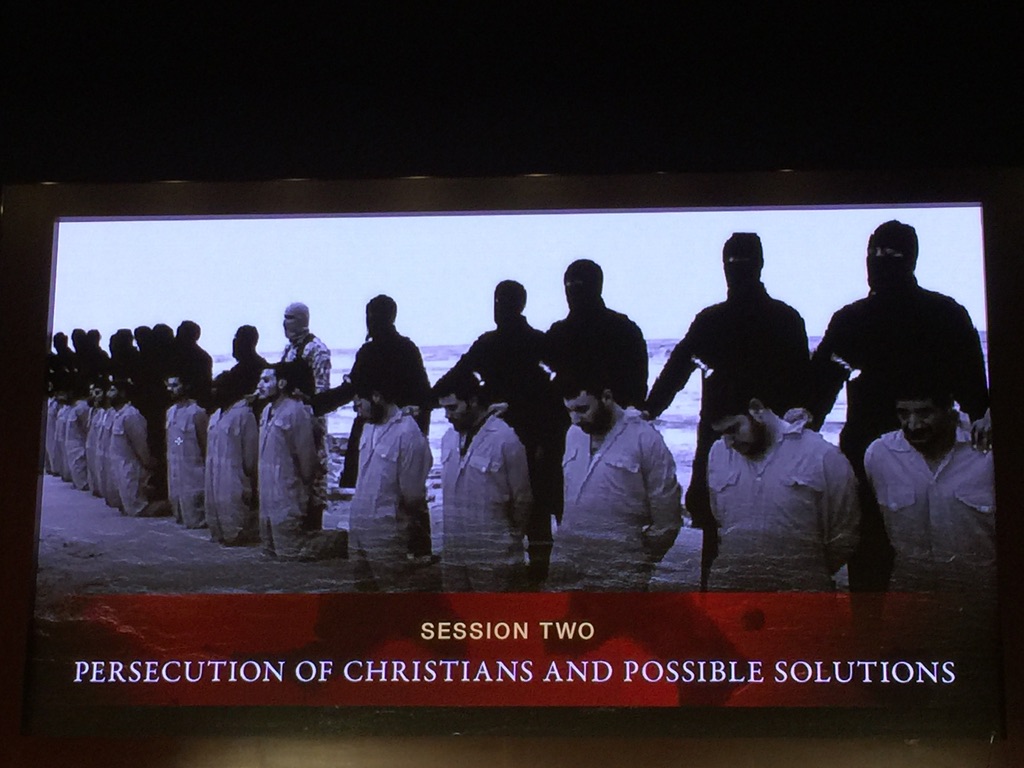

Raheb’s Politics of Persecution offers a geopolitical analytic lens as methodology; as he argues, it is impossible to consider the Middle Eastern Christian condition outside of these broader contexts—that is, how such communities are politically and religiously depicted by the west. As Raheb contends, the west’s focus on the plight of Middle Eastern Christians stops short of advocating for substantive and structural change that would impact the material conditions of all peoples in the region, exceeding the bounds of religious kinship. Raheb notes that western empathy for persecuted Christians need not be inherently negative, so long as it attends to the comprehensive sociopolitical positioning of such communities. Such positioning must go beyond fantastical displays of their plight wherein they become nothing more than “an orientalist cliché that is subordinate to Western interests” (41).

As a Christian community in Egypt, Copts have variously experienced forms of discrimination and outright persecution by governing authorities, political factions, and their Muslim neighbors. Yet, the manifest anti-Coptic discrimination in Egypt is also the primary area of interest to U.S. foreign policy, to Copts themselves inside of Egypt, and among diaspora communities, especially the United States. The importance of the Coptic plight to Coptic communal formation, most especially in diaspora, has typically been eschewed in progressive circles. This has had consequences for political mobilization, shaping the possibilities of alternative forms of solidarity in diaspora contexts. It has in turn binded the imaginaries of liberation that flow in and out of Egypt.

Raheb is right to note that Middle Eastern Christians, like the Copts, have often been “Orientalized, victimized, and minoritized” and many people in the west “claim to speak on their behalf” (4). Yet, some of those people in the west tend also to be part of Middle Eastern Christian diasporas, which also speak on their own, tell their own stories, and indeed have “looked to the West for protection, aid, and political backing” (39). Such Middle Eastern Christians do so in the diaspora. And while Raheb champions those Christians who remain in the region “because this is where their national, religious, and cultural roots lie, this is where they belong, and they will not be satisfied with being less than equal citizens” (141), this is not the choice that all Christians in the region make. Others choose to migrate in search of a better life, whether through the Green Card Lottery (in the case of Egypt) or by seeking asylum or family reunification.

In my ethnographic work, transnational Coptic life has offered an intimate window into how hegemonic political forces shape diasporic communities in their translation of collective praxis—the transformation of political orientation, racial identification, and religious solidarity. The transnational lives of my interlocutors I take to exist within multiple realities, following what anthropologist Ghassan Hage has called “diasporic lenticularity.” This approach directs our attention to how migration has impacted life beyond homeland/diaspora framings. Among Copts, the narratives and collective memory of violence and persecution that shape diaspora communities also (re)circulate back to Egypt and are modulated in turn; the news of violent incidents against Copts that occur in Egypt travel to places like the United States, which galvanize American Coptic politics and shape Coptic placement into an American racial-religious landscape.

Minority, a concept that developed through the entangled structures of the liberal European state and its colonies, promises to make politically visible the marginalization of a group within a polity. The plight of Coptic Christians stakes its legibility on the grammar of minoritization—that Copts are persecuted and require social and political redress beyond the authority of the Egyptian nation-state and, instead, through the mediation of the global, imperial power of western countries, most especially the United States. Yet even while Coptic life in Egypt exceeds this grammar (of religious persecution and marginalization), its processes continue in diaspora. In this latter context, they are bolstered by translational activism, Christian majoritarianism, White supremacy, and the exceptionalism of U.S. empire. Minoritization shows its plasticity as it is translated across borders and through empire, sustained by the very contradictions—between homeland and diaspora, race and religion, minority and majority—that seemingly undo it.

Religious discrimination and the relevance of Copts’ Christianity travels with them to the United States, but it also homogenizes and simplifies readings of Christian discrimination in Egypt as well.

This bind that Copts and Middle Eastern others must traverse in their transnational community-fashioning and political activism is one that has framed knowledge production on them in scholarship—as liminal, peripheral, and problematic because of their contested relationship to Islam, Muslim-majority governance, and the broader Middle East. We can better remedy their erasure—between scholarship and political mobilization—by taking the experiences, narratives, and interests of Copts and Middle Eastern others seriously as part and parcel of mainstream discussions and debates, as integral for us to better understand nationalism, empire, class, and migration.

Placing Christians in the center of Middle Eastern historical and broader geopolitical developments, as Raheb’s book does, most certainly diverges from typical renderings of the region, which relegate minority communities to marginalia. As such, The Politics of Persecution offers a much-needed fresh perspective on Middle Eastern Christians and the effects of European colonialism, U.S. empire, and geopolitical intervention. It provides a vital analysis of the representation of Middle Eastern Christians by the West and a necessary argument advocating for a renewed look at their agency—whether in their forms of resistance to persecution politics or their power to shape such discourses of global anti-Christian plight. Ultimately, as a thought experiment on hope, Raheb seeks to refocus attention on the potentialities for abundant Christian life instead of death and ruin in the region—even in spite of varying imperial forces that flow in and out of such transnational communities.

This review draws from the following roundtable contribution: Candace Lukasik, “Migrating Minority: Persecution Politics in Transnational Perspective.” International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 54, no. 3 (2022): 541–46.