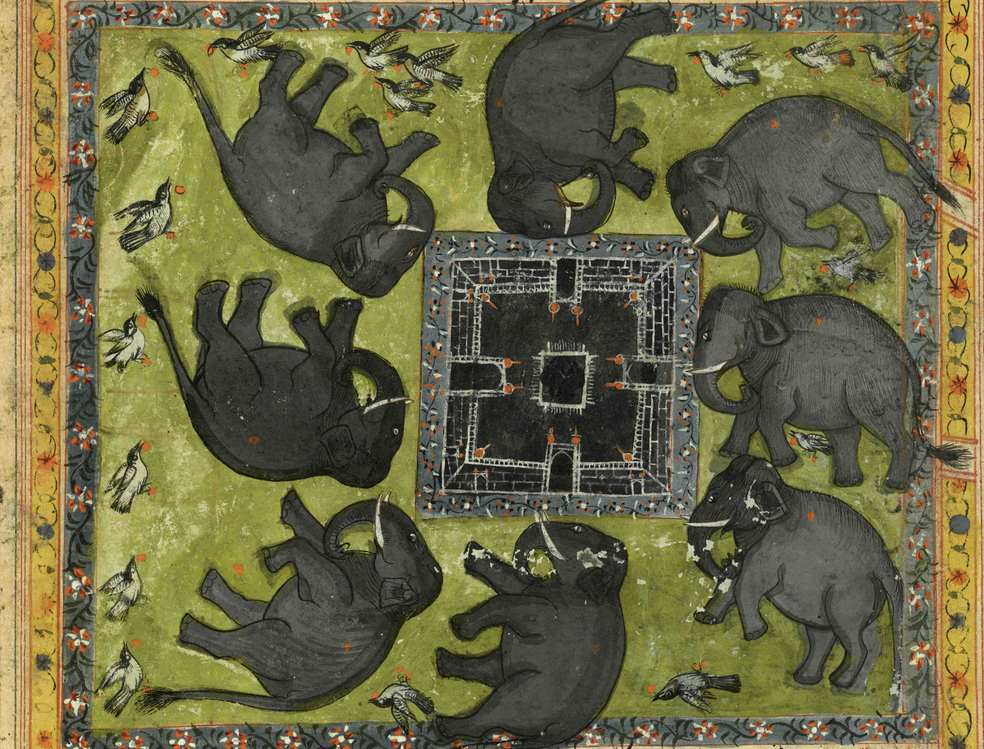

A well-known tradition in Islam records that on the year of the prophet Muhammad’s birth, Abraha, the ruler of Yemen, laid siege to Mecca. The caretaker of Mecca at the time was ‘Abd al-Muttalib, Muhammad’s grandfather. As the population evacuated the city to the surrounding hills, ‘Abd al-Muttalib entreated Abraha to release his camels to make sure they would not perish in conflict. Abraha’s intentions were to take the city and raze the shrine that housed the city’s gods, the Holy Ka‘ba, to the ground. At this point, the astonished Abraha reportedly lost all respect for ‘Abd al-Muttalib: what kind of leader would prioritize mere livestock over the house of God? Upon noticing Abraha’s disdain, ‘Abd al-Muttalib explained, so the tradition goes, that his camels were his responsibility. The shrine, on the other hand, he remarked, was God’s responsibility, and God would protect it. One of the units in Abraha’s army was an elephant cavalry that dramatically refused to ram the Ka‘ba, and ultimately, a flock of birds descended to lay waste to the aggressors. It was in reference to this event that the one hundred and fifth chapter of the Qur’an, entitled “The Elephant,” was revealed.

My mind dwells on his tradition when I think of Jerusalem today. ‘Abd al-Muttalib had is priorities in order. He could have put his life, and the lives of countless innocents, on the line to save the sacred shrine of Mecca. He assessed his odds and chose not to resist. That choice was grounded in a profound belief in divine providence and power. In light of this tradition, one might ask whether it is our belief in God, or lack of belief, that makes us—Jews and Muslims—vie for the land? And let us not forget the third in the trinity of Abrahamic faiths, Christianity. If ‘Abd al-Muttalib cared so much for his herd, what would the very Lamb of God say about what is happening in the Holy Land today? In these brief reflections, I draw on perspectives from each of the three Abrahamic faiths on how to think and feel about Jerusalem: Yerushalayim, “abode of peace”; al-Quds, “The Holy.” It is a harsh and bitter irony that the holiest sites of the Abrahamic faiths are either abodes of exclusivism, such as Mecca, or abodes of strife and conflict, such as Jerusalem. How can these sites become symbols of peace, love, and the fellowship of humanity, instead of triumphalist bastions that have become hollower than they are holy, whether by consumerism or conflict?

The word ger (or a derivative), meaning “stranger,” appears more often than any other word in the Torah. One of my favorite references is Exodus 22:20: “And a stranger shalt thou not wrong, neither shalt thou oppress him; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.” This verse is among those that are cherished by students of scripture, for it gives a not just a command, but also the reason for the command that becomes enshrined as an eternal principle. The reasoning this verse provides is none other than the celebrated golden rule: do unto others as you would have done unto you. Rabbi Hillel famously summed up the whole Torah in one sentence: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor; all the rest is commentary.” We should pay attention when a tradition articulates its first principles so clearly. Is there a contradiction with Exodus 22:20 and the illegal occupation and settlement of lands, the overwhelming use of military force, and the crushing treatment of gerim that borders on apartheid? The answer to this question is yes, you bet there is.

But, what is the alternative? Israel argues that the circumstances it confronts today are exceptional and the threats existential. If the alternative is annihilation, then the first principles must be suspended in favor of survival. Morality follows life in order of priority. Bombastic rhetoric and violent resistance by the Palestinians only serve to fuel further aggression. The charter of Hamas begins with this statement from the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hasan al-Banna: “Israel will exist and will continue to exist until Islam will obliterate it, just as it obliterated others before it.” This is not helpful for the Palestinian cause. In fact, it is a total disaster, both morally and strategically. Especially since the resistance is so asymmetrical, involving the desperate and indiscriminate targeting of the other side and the never-ending sacrifice, not simply of camels, but of generations of human beings.. Where are the ‘Abd al-Muttalibs today? Make no mistake: Hamas is a resistance movement, but the manner of its resistance has only legitimized further aggression, land grabbing, isolation, starvation, loss of moral clarity, let alone moral high ground, and now, from what it looks like, the loss of Jerusalem.

The Palestinians need to ponder the cost of protracted resistance to innocent lives on both sides—however legitimate that resistance may be—against a foe that has overwhelming military, economic, and technological advantage. One of the arguments the Jewish nation has against the Palestinians is that they are part of a larger Arab nation, while the Jews have no home of their own. This argument is doubly mistaken. One, all Arabs are not the same. The Palestinians are no more similar to the rest of the Arabs than the modern day Irish are to Australians or Canadians. It would be absurd to ask modern day Australians, for example, to transfer themselves to other “white” English speaking lands to make room for aboriginals so they can establish an aboriginal democracy. What is a little difference in accent, right? Wrong! Two, it is wrong because it assumes that democracy can be constructed through demographic control by manufacturing a majority unjustly through a systematic program of ethnic control, if not ethnic cleansing.

How could this happen as the world looks on, eyes wide open? Surely, Israel is on the wrong side of history. But it is on the right side of power. The Arab and Muslim world is an embarrassing disgrace when it comes to reaching for the moral high ground or to reaching for power. What if we were to compare the sins of Israel to the sins of Saudi Arabia against Yemen, ISIS against Iraq and Syria, and the Syrian regime against its own people, just to take a few immediate examples? As a Muslim, I cannot in good conscience point a finger against Israel without four fingers pointing right back at me. And as a citizen of a nation—the United States of America—that has provided material and diplomatic cover for both Arab and Israeli policies for decades, the finger I point at Israel may as well be pointing back at me as well, as if I were pointing in a mirror. If everyone and everything is so messed up—Israel, the Arabs, the Americans, and the rest of the Muslim world—how is it possible to have any kind of moral stance, whether in favor of Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions or in favor of more military and economic aid that ends up supporting occupation and settlements?

The answer might at first appear simple: clarity comes with focus. More occupation on the one hand. More resistance and terrorism on the other. The problem is that we often choose to focus on the speck in the stranger’s eye instead of the beam in our own. If Americans worked to reform politics and special interests in America; if Israelis were critical of their mistreatment of Palestinians; if Palestinians gave up all forms of armed resistance and anti-Semitism, accepting at least partial blame for the predicament they find themselves in; if the Arab world showed more wisdom in how it invested its exorbitant wealth and forged unity among its ranks; then we might make progress towards the peaceful resolution of seemingly intractable conflicts. Unfortunately, what appears simple at first is more complicated than it seems. That is because many of us have hybrid identities: some Muslims are also Americans, some Palestinians are also Christians, some Israelis are also Arabs, some Americans are also Israelis, and the most ardent of Zionists are born again evangelical Christians. We each need to look within before causing chaos without.

Introspection, however, is a hallmark of spiritual traditions, not secular politics. Like people, religion and politics can also have hybrid identities. Secular aims can mask themselves as religious: “We don’t want their oil, we just want to spread God’s gift of freedom!” Religious aims can appear in the garb of secular objectives: “We need more land only because we need strategic depth!” The sacralization of partisan politics and secularization of spiritual traditions are the cancers of the world, and they have become malignant in an age of social media and cable news that is driven by market forces. Simple issues like what’s happening in Israel-Palestine become complicated. And complicated issues like terrorism and its causes become simple. Morality is compromised. Intellect is insulted. History is lost. 9/11 happened out of the blue. “We didn’t ask for this war!” “They hate our freedom!” According to this narrative, Christian America in under attack, and secular America does the dirty work needed to defend our borders against the barbarians. The Muslim world is no different. “The problem is colonialism…Hey, boy, bring me some more tea!” O Jerusalem! “A land without people for people without land!” In our own ways, we are all hypocrites.

Although the conflict is portrayed as being between two sides, Jerusalem is the city of three faiths. And Christians find themselves on both sides. As a significant portion of the Palestinian population, Christians are being crushed under the weight of occupation and the external imposition of a wholesale identity that equates “Palestinian” (and “Arab” in general) with “Muslim.” As a powerful lobby in the US, fundamentalist Christians are driving a brutal policy of exclusion and dehumanization in the name of an apocalyptic end-times ideology. But all generalizations eventually break down. There are also many non-Palestinian Christians who believe that the Christ of the Cross is with the oppressed, and the oppressed are the Palestinians. Similarly, there are noble Jews whose love and activism on behalf of the Palestinians at times earns them the title of “self-hating” or “refusenik.” All they are doing is upholding the moral commandment of helping the oppressed. They are the true Israelis, in the spirit of a well-known prophetic tradition where Muhammad is reported to have asked believers to support other believers, whether they are oppressed or the oppressors: one helps an oppressor by restraining him, not strengthening him. There are many more voices for peace than of conflict at the grassroots—on all sides—but the market has been captured by secular states and war industries that profit from instability. Of course, foolish religious actors—also on all sides—have played right into the hands of power politics, secular interests, and media sensationalism.

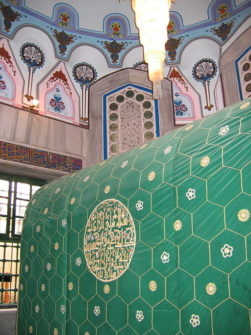

The Quran says that “God’s earth is vast,” enjoining believers to move about freely if they find themselves oppressed. The Quran also says that it is the righteous who will inherit the Holy Land. But no piece of religious real estate is worth innocent lives or losing moral high ground, as Abd al-Muttalib demonstrated so long ago. The words of the thirteenth century Andalusian mystic Ibn ʿArabi, so often quoted by my colleague Ebrahim Moosa, ring true, comparing the dignity of human beings to the value of holy shrines made of stones:

Birds circumambulate Me, hour after hour

From passion, love and desire to touch My legs

The manner in which the noblest of prophets performed the pilgrimage

A rite, that intellect declares, makes no sense

The Messenger, then goes further, and kisses a stone

But how, he declares, can the revered status of the sacred house ever compare to the value of a human being?

In my identity as a Muslim, I pray that Muslim nations develop some sense to support the Palestinian struggle with a unified voice in international forums with dignity and resolve. As a neighbor and well-wisher of Israel, I pray that the Jewish nation is able to show generosity and kindness to those who are now strangers in their own land, as the Torah commands. As an American, I call on the US government to be just and wise in its domestic and international policies, wielding its tremendous influence and power responsibly and fairly.

I believe that if and when the time of crises has passed, whether Jerusalem is entrusted to Jews, Christians, Muslims, or shared by all three, its custodians will honor it by welcoming everyone as visitors, guests, and pilgrims in peace. The problem right now is a conflict on who will be Jerusalem’s permanent residents. Here again, the wisdom of our faiths guides us. Nobody is a permanent resident anywhere on earth. “Be in the world as a stranger or traveler,” said the prophet Muhammad. We are all travelers. We are all strangers. Generations come and go. With this reality in mind, let us tread with humility as the fate of Jerusalem hangs in the balance. Rabbi Hirsch, in his commentary on Exodus 22:20, writes: “The great, meta-principle is oft-repeated in the Torah that it is not race, not descent, not birth nor country of origin, nor property, nor anything external or due to chance, but simply and purely the inner spiritual and moral worth that is the nature of a human being, that gives him/her all the rights of a human being and of a citizen.” Jerusalem belongs to us all. Jerusalem is not Israel’s to take, and it is not America’s to give. Nonetheless, if Israel upholds the meta-principle of Exodus 22:20, which is the very same principle offered by the prophet Muhammad in his last sermon, echoing the Great Commandment of Jesus “to love thy neighbor as thyself,” then God may once again make Israel its custodians.

From where I’m standing, that is a very big if. An even bigger if is whether the Palestinians can forgive Israel. Who will take the first step to build trust? From which camp will our Abd al-Muttalib emerge? It takes two ifs to tango. Our religious traditions are a resource rather than hindrance for peace, if only we could tap into them for the right kind of inspiration.