In 1977, a few months prior to his arrest and subsequent murder by the South African apartheid state, Steve Biko, widely known as the leader of the Black Consciousness movement, said the following:

There is no running away from the fact that now in South Africa there is such an ill distribution of wealth that any form of political freedom which does not touch on the proper distribution of wealth will be meaningless. The whites have locked up within a small minority of themselves the greater proportion of the country’s wealth. If we have a mere change of face of those in governing positions what is likely to happen is that black people will continue to be poor, and you will see a few blacks filtering through into the so-called bourgeoisie. Our society will be run almost as of yesterday. (155–56).

48 years later, it is safe to say that Biko called it. Present day South Africa, over three decades since the end of apartheid, remains severely unequal. This inequality continues to exist along apartheid racial lines. And this is not surprising. If you create a politico-legal system which massively privileges White people in terms of land, education, wealth, and opportunity at the expense of Black people, and then replace this system with supposedly non-racial neoliberal economic policy, very little actually changes. The majority Black population, having previously been forcibly removed and relegated to particular sites and occupations under apartheid, are no longer legally barred from owning land and living and working wherever they would like. Instead, they are barred by the “free” market and various other structural obstacles. This leaves the majority unable to afford or access safe, let alone well-situated, housing, or sound economic opportunities, due to centuries of systematized oppression.

112 years after the 1913 Native Land Act (which, in a classic case of colonial expropriation of land without compensation, granted over 80% of South Africa’s land to the White minority), White people—who make up just 7% of South Africa’s population—still own close to three quarters of the country’s farmland. The distribution of other forms of wealth follows similar patterns.

Into this context, the Expropriation Act—the piece of legislation which provoked the wrath of Trump and his anti-woke brigade—was introduced in January 2025 after years of consultation, discussion, and failure to address the injustices of the past. In line with the provisions of the globally lauded South African Constitution, the Act, in exceptional cases, makes allowance for the state to expropriate property for reasons of public interest, and in even more exceptional cases, makes expropriation without compensation possible. The processes outlined by the document, through which both expropriation with and without compensation are governed, are detailed and stringent. The conditions under which the latter is possible are outlined in section 12 (3) (d) of the Act. Essentially, in relation to private land, for expropriation without compensation to be ruled just and equitable (a pre-condition for such action), this land is required to either be unused (with no plans for development of the land or income generation on it) or abandoned. Thus, the flurry of outcry around this is unjustified. Similarly, Trump’s claim that White Afrikaner South Africans are experiencing “government sponsored race-based discrimination,” his fabrications about a “White genocide” in South Africa (spoiler alert: this is not true), and his subsequent welcome of White Afrikaners as “refugees” into the US, are ludicrous. And if not so dangerous in terms of their intended delegitimization of South Africa’s democracy (and all related implications thereof), and the deeply problematic and untrue narratives that they act to justify, they would be laughable.

While the ridiculousness of this situation would make it easy to simply dismiss as unworthy of attention, we would be remiss in doing so. This current US-South Africa debacle is a microcosm of some much broader dynamics at play. As such it holds important potential for shedding light on this current moment.

South Africa has always been a site of struggle—a deeply contested landscape where there are clear clashes between marginalized (but majority) interests and hegemonic (but minority) ones. This was most overt under the apartheid system, where oppressed and oppressor identities were very (forgive me) black and white and constructed through a myriad of legislation. But while these delineations are somewhat more opaque today, shrouded beneath “rainbowist”[1] post-apartheid narratives—although these myths were effectively disrupted by the 2015 and 2016 #Fallist calls for decolonization—they remain ever-present. In this regard, there is something deeply sinister about Trump’s singling out of White Afrikaners for refugee status. While those with a deeper awareness of South Africa’s colonial history recognize that the British colonizers played just as, if not more (how to compare colonial violence?) harmful a role as the Dutch descendants, the history of apartheid as implemented by the Afrikaners is much more popularly known. Thus, Trump’s singling out and extending of “solidarity” towards White Afrikaners appears to be a not-so-subtle nod to apartheid—and indeed a call to “make South Africa great again” in the same way that “make American great again” is a not-so-subtle nod to slavery and White supremacy. If these intentions weren’t already abundantly clear in Trump’s actions, the words of US Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau to the Afrikaner “refugees” upon their arrival to the US on May 12, 2025, sealed the deal. He welcomed them effusively, saying, in what can only be understood as a blatant celebration of apartheid, “We respect the long tradition of your people and what you have accomplished over the years.”

Inter-Racist Solidarity

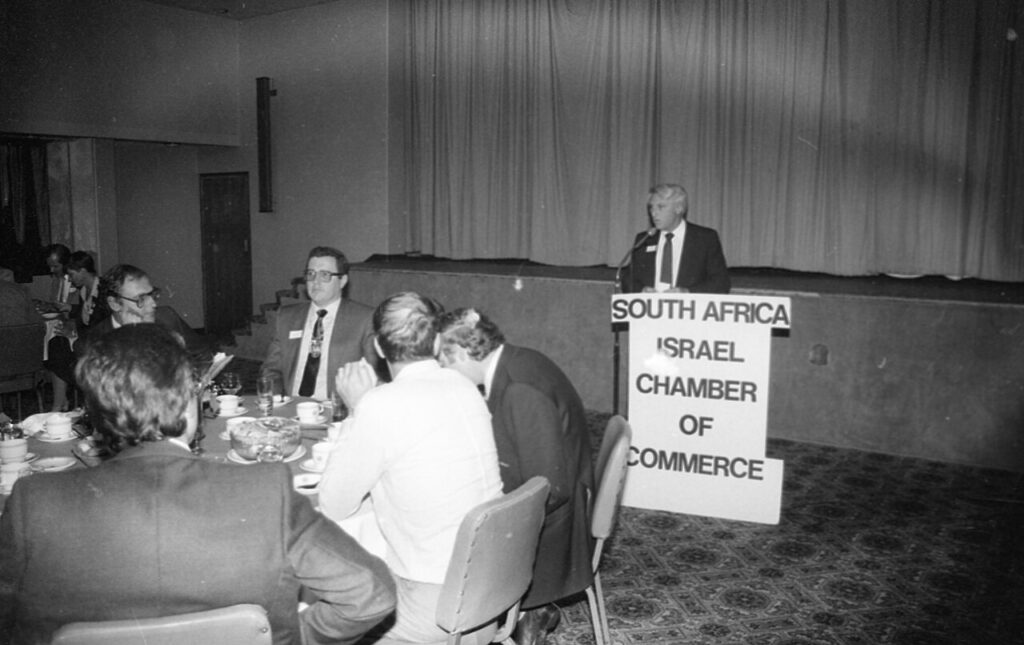

Salim Vally categorises the close historical relationship between the South African apartheid state and the Israeli state as a case of “inter-racist solidarity”[2]. This term aptly describes the current US-White Afrikaner dynamics, as well as the broader convergence and consolidation of imperial, right wing, and White nationalist forces that we are seeing today. Indeed, the mention and condemning of South Africa’s ongoing International Court of Justice case—where the case is being argued that Israel’s actions in Gaza after October 7, 2023, amount to genocide—in Trump’s executive order makes clear that the administration’s response to South Africa is not just about South Africa. It is simply part and parcel of this inter-racist solidarity network that is currently being established, nurtured, and consolidated through various means.

As such, everything that threatens the right-wing White nationalist (yet transnational) empire is under the microscope. And the very existence of post-1994 Black-led South Africa is a threat, representing the failure of this empire’s White nationalist vision. This threat is magnified by South Africa charging Israel with genocide at the ICJ, and even more so given the global South connections and solidarities that this move has inspired. Of similar threat are the mass popular movements of solidarity with Palestine taking place globally, as are the Movement for Black Lives and the so-called “woke” politics and DEI interventions of recent years.

As we are seeing ever more clearly, this empire does not take kindly to threats. It is organized and knows how to mobilize to accomplish its goals. This is evidenced in the speedy travel, broad reach, and buy in to “White genocide” myths. It is evidenced in the recent expelling of Ebrahim Rasool, South African ambassador to the US. It is evidenced in the cutting of USAID and other US funding to South Africa. It is evidenced in the absolute impunity with which the US is operating in its continual funding of the genocide in Gaza. It is evidenced in Elon Musk’s encouragement and support of right-wing nationalist movements in “at least 18 countries.” It is evidenced in the current spate of unlawful and highly irregular arrests, detentions, and deportations of individuals seen as transgressing or challenging US White nationalist ideals. It is evidenced in the massive amounts of money raised for the legal defence of Daniel Penny, a White 24-year-old marine corps veteran, after he choked to death Jordan Neely, a 30-year-old unhoused African American man—and the broader pattern of which this case is representative. And of course there is much more evidence one could cite.

As this conversation makes clear, race remains a salient node of analysis, carrying clear material and structural implications. This reality notwithstanding, we must be particularly careful not to essentialize race. In this regard, Salim Vally and Enver Motala caution against uncritically reproducing “the apartheid state’s usage of racialised forms of consciousness” (39). Thus, it is necessary to hold the tension of race as both social construct and materially salient, in order to challenge and not reproduce the harms of racially oppressive realities. This tension is important in this conversation about inter-racist solidarity and White nationalist empire, as it is clear that this empire quite often has Black and Brown allies—whether this be the Black representatives at the UN voting on behalf of the US against a ceasefire in Gaza, or Gulf state leaders falling over themselves to secure massive deals with Donald Trump. In thinking about a framework to help understand this phenomenon, I offer two considerations. Firstly, it is important to recognize the fundamentally socially constructed nature of racial categories, which has meant that these categories are impermanent and ever shifting—the apartheid state’s contentious “pencil test” (one of the apartheid state’s official racial categorization tests involving sticking a pencil into a person’s hair and letting go to see whether it fell out or remained) evidence of this. Secondly, the capitalism aspect of racial capitalism shapes these relationships of “inter-racist” solidarity according to profit margins, in ways that can actually be quite racially inclusive. Here however, it is important to take seriously various Black thinkers’ critiques of Marxist understandings that erase race in favor of a pure class analysis. White nationalism is here and increasingly asserting itself in worrying ways, yet even White nationalism will put up with some Black and Brown people if the money is right.

The Role of Religion in Inter-Racist Solidarity

We would be remiss in failing to acknowledge the way that religion —conservative evangelical Christianity in particular—often underpins and is appropriated in these configurations of power. As outlined by Mitri Raheb, religion is often mobilized to act as the “software” that whitewashes, justifies, sustains, and sacralizes the “hardware” of empire. As such, through immaculate theological manoeuvring, South African apartheid was configured and framed as divinely ordained. Similar techniques have strategically shaped and deployed Christianity to effectively serve and provide the foundations for colonialism, slavery, land theft, and genocide over numerous eras and geographical contexts. Today these techniques theologically justify Israeli occupation, settler colonialism, and genocide. In this regard, it is not mere coincidence that the US, Israel, and White Afrikaners in apartheid South Africa have understood (or at least framed) themselves as nations or people chosen by God. This narrative, among others, works to justify and even sacralize the atrocities that these groups carry and have carried out. And importantly, as evidenced in the testimony of one of the Afrikaner “refugees,” while these notions of chosen-ness are held at the level of nations, they filter down to individuals. In his testimony, Mr. Kleinheis—a self-declared “religious person”—claims that his selection was, for him, evidence of his own chosen-ness, stating that “to be in this first group is an act of God.” He goes as far as to say, “if he (God) didn’t want me to come, I wouldn’t be here,” tacitly making the case that God is behind this whole saga, sanctioning narratives of “White genocide,” ordaining (or even instigating) the White House’s inter-racist solidarity moves, actively demonizing and rejecting actual refugees, and ultimately blessing the White nationalist empire.

Conclusion: The Hope of Transracial Solidarity

This current moment should be understood as one of heightened mobilization and consolidation of inter-racist solidarities for the purposes of securing an imperial White nationalist (yet transnational) vision. Conversely, however, there are rich histories of resistance through which such inter-racist solidarities have been countered. Notably, where the apartheid regime constructed and weaponized racial categorizations according to colonial “divide and rule” tactics, while consolidating its own power by various means, the Black Consciousness movement combatted this with what could be called “trans-racial solidarity.” By refusing apartheid race categories and reframing blackness as not just a racial identity but a political one—indicating an unwavering commitment to liberation—this movement emphasized and strengthened the connections between the struggles of the oppressed. Such trans-racial solidarity was and remains a powerful counter to that of the inter-racist kind. Hence, in these times, the martyred prophet Biko has much left to teach.

[1] Archbishop Desmond Tutu described post-1994 South Africa as a rainbow nation, and while perhaps unintentional, this descriptor has come to do the work of presenting South Africa as a happily diverse but unified society, belying, plastering over, and thereby sustaining the severe inequalities that exist. As analyzed by prominent South African feminist academic Pumla Gqola, “rainbowism” has functioned as an “authorising narrative which assisted in the denial of difference” foregrounding “racial variety even as it does not constructively deal with the meanings thereof” (99).

[2] Despite its staunch pro-Nazi origins, the South African apartheid state ruled by the National Party (the White Afrikaner party that instituted apartheid in 1948) grew to develop strong and intimate ties with the Israeli state. Among other things, these ties involved extensive military and economic collaboration. On this point, see Francesco Pontarelli’s interview with Salim Vally.