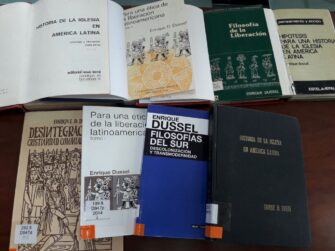

Since the 1980s, Enrique Dussel has been regarded as the most important scholar in the fields of philosophy and theology in Latin America. An early contributor to liberation theology (teología de la liberación), a pioneering leader in the concurrent field of liberation philosophy (filosofía de la liberación), all the while being a highly respected historian of the Catholic Church in his own right, Dussel’s work spanned fields, geographies, and world history in an effort to dismantle the Eurocentric and colonialist pretensions of modernity. His contributions to these academic fields are simply too numerous to begin to list here. Without a doubt, the epistemic decolonialization of these fields is at the front and center of his scholarship. However, the full potential of his work would be deficient if its reception were limited to a disciplinarily decadent interpretation that refused to cross boundaries. I argue that one of the most significant legacies of Dussel’s work is the urgency to rethink disciplinary divides with an eye toward epistemic decolonization. The relation between history and philosophy and the relation between history and theology are good examples of this interdisciplinarity.

The fact that Dussel was a contributor to the emergence of both liberation theology and liberation philosophy has often resulted in a misguided, if not outright dismissive, reception of his work from the fields of theology and philosophy. On one hand, some theologians argue that his liberation theology is not properly theological due to the strong influence of Marxism on its development. They argue that this influence leads his theological work to be a merely Marxist secular philosophy in disguise. On the other hand, some philosophers argue that his brand of liberation philosophy is not philosophical enough due to its close historical and theoretical relationship with liberation theology. Ofelia Schutte argues, for example, that if his philosophical work is not simply a theology in disguise, then at least it is a secular imitation of liberation theology (174). This is the case even though Dussel himself never sought to blur the boundary between philosophy and theology. Instead, he kept a strict distinction between the two discourses based on a division between faith and reason. For him, whereas philosophy is geared toward a universal secular community of reason, theology is geared toward a particular religious community of faith.

One of the most significant legacies of Dussel’s work is the urgency to rethink disciplinary divides with an eye toward epistemic decolonization.

Nevertheless, such formal distinction did not prevent creative and critical explorations of the ways in which the theological and the philosophical come together. In my view, these explorations are some of the most fertile moments in Dussel’s work. We see this in Dussel’s politico-philosophical study of Paul the Apostle. Here, a formal distinction between philosophy and theology is maintained in a way that seeks to overcome philosophy’s Enlightened secularism.

Without stepping into the ecclesiastical domain of theology, the philosopher can examine texts or topics that have traditionally been taken up in theology in the interests of determining a potential universal rationality. To be clear, this move is not the methodological discovery of a “philosophical theology” (which applies philosophical methods to elucidate theological frameworks) nor a “political theology” (which more narrowly analyzes the political field from the sectarian perspective of a religious tradition). As I have argued elsewhere, this move instead denotes the development of a dialectically postsecular philosophy that is invested in overcoming the ways in which the modern secular/religious divide has been falsely universalized through the coloniality of knowledge.

A more intricate instance of this exploration between the theological and the philosophical can be seen in Dussel’s The Theological Metaphors of Marx, a text that will be published for the first time in English translation in 2024. This text reconstructs Marx’s critique of theology as a critique of politics in a way that re-fashions political philosophy as an “anti-fetishist” philosophy of religion, where profane sacralization is diagnosed to be the root cause of political domination. While Dussel would write this text intermittently over a 20-year period parallel to the historical development of liberation theology, his argument largely stands on postsecularist philosophical grounds rather than theological ones. In this regard, it is similar to another heretically Marxist text: Ernst Bloch’s Atheism in Christianity, in which the German philosopher aims to establish a conversation between Marxism and religion “purged of ideology” (in the case of the latter) and “purged of taboo” (in the case of the former) (51). Interpreters who miss this methodological nuance end up all-too-quickly diagnosing the failure of The Theological Metaphors of Marx as a forced theologization of secular concerns. But this conclusion misses the entire point of the text, which is to rescue the critical value of theological metaphors as a critique of politics–which is to say, to probe the theological as the unspoken infrastructure of the politico-economic. It is in this way that The Theological Metaphors of Marx philosophically uncovers Marx’s own “proto-theology” or “implicit theology” made possible by the conceptual labor of a metaphorical language (18).

At the crossroads of the theological and the philosophical, the task of the decolonial postsecular philosopher is to diagnose the fetishisms or “false names,” which is to say, the false gods of the modern/colonial world that demand worship. This is why an atheist “anti-fetishism” is the very “first thesis” of liberation philosophy: it is an atheism of the fetish. And that secularism is one of these fetishes that plague modern philosophy is why a postsecularist impetus is important for the purposes of epistemic decolonization.

This is not to say, however, that all “dialectics of secularization” are absolutely doomed to culminate in irredeemably colonialist and fetishistic dynamics, as the ideology of secularism has done in modernity. This is why there remains, after all, a distinction between philosophy and theology, itself based on a division between faith and reason. If one can diagnose the irrational fetishisms of modernity, it is because somewhere a critically emancipatory and universal kernel of rationality remains alive. “There is no liberation without rationality,” Dussel claims, “but there is no critical rationality without accepting the interpellation of the excluded, or this would inadvertently be only the rationality of domination” (36). Accordingly, epistemic decolonization can be recognized as the interpellation of the excluded that calls out the fetishisms of a colonialist modernity. Evidently, this is not a crude call for the abandonment of modernity, nor simply a reaction against it. It is, rather, a creatively dialectical critique that goes through modernity itself. In Dussel’s terms, it is a “transmodern,” project, rather than an anti-modern or a postmodern one.

Decolonizing the relation between philosophy and theology is likewise not simply a matter of just blurring or undoing the boundaries between them. The lesson from Dussel’s work is to embrace the creative dialectics of decolonization which demands a new transmodern way of thinking about the points of mutual correspondence between philosophy and theology in a way that allows for liberatory interpretations of the world, beyond the fetishisms of modernity (such as secularism). At least this will be but one of the many legacies that his work will allow future generations to explore.