Decolonizing Buddhist Studies

Religious studies is finally beginning to come to terms with its colonialist past. Discussions related to decolonizing religious studies are becoming increasingly prominent, not only in forums like this blog, but also in places like the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion, the main academic gathering for scholars of religion in the US. We still have a long way to go, but the fact that these conversations are even happening is promising.

Within religious studies, however, scholars of Buddhism have remained largely absent from these discussions. Buddhist studies, on the whole, has not acknowledged, let alone addressed, issues of colonization, white supremacy, and the erasure of Asian people and cultures within the field. And with the news of a white man murdering Asian women on March 16, 2021, an attack that followed in the wake of increased anti-Asian violence related to misinformation about the coronavirus pandemic, scholars of Buddhist studies need to acknowledge where we stand in all of this, beyond simply expressing our outrage at specific incidents of explicit hate.

Buddhist studies, on the whole, has not acknowledged, let alone addressed, issues of colonization, white supremacy, and the erasure of Asian people and cultures within the field.

Buddhist studies needs to confront the fact that our discipline, as it currently exists within the US academy, is overwhelmingly white and has benefitted from colonialist assumptions since its inception, yet it is built on the backs of Asian Buddhist communities. We have not yet, as a discipline, collectively and seriously considered the ways that we are complicit in this. To omit such a reckoning is to perpetuate its own kind of racial injustice.

Learning from Buddhist Practice Communities

In the practice of Buddhism in the US, there is a long history of white communities of convert Buddhists appropriating Buddhism by excluding Asians and ignoring the cultural aspects of Asian Buddhist traditions. Buddhist convert communities are beginning to wrestle with this history within their own sanghas by developing programs for BIPOC practitioners, as well as programs for white allies to confront systemic racism.

The presence of such efforts in Buddhist practice communities stands in stark contrast to the absence of that kind of work in the academic study of Buddhism. While Buddhist studies is not the same as Buddhist practice, these two enterprises are not wholly separate, either. There is considerable overlap between academic scholars and practitioners of Buddhism in the US, particularly in the sense that both communities have directly benefitted from the work of Asian Buddhist teachers and communities, often without acknowledging their contributions. With this in mind, it is especially troubling that Buddhist studies has been so slow to confront a history built on extractive methods and Orientalist assumptions.

These Issues Are Systemic

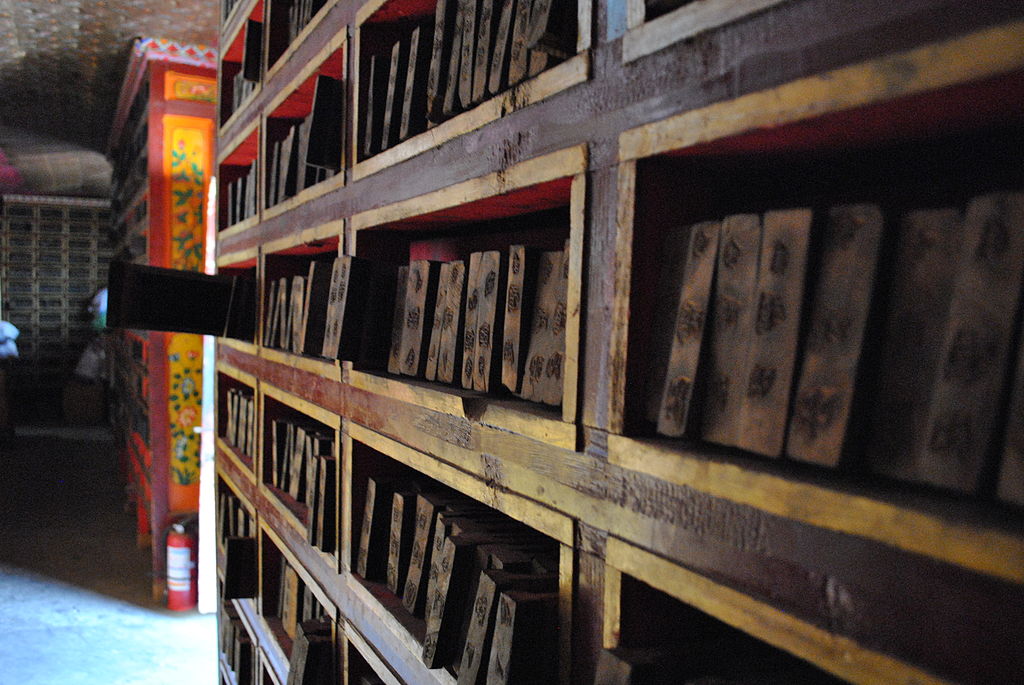

To be clear: I am not suggesting that individual scholars of Buddhism are actively engaging in erasing Asian people’s cultures. The vast majority of scholars of Buddhism in the US have a deep respect for the traditions and cultures that they study. The point, rather, is that Buddhist studies as a whole has failed to acknowledge systemic issues that need to be laid bare. Buddhist studies in the US is overwhelmingly white (and overwhelmingly male, although this is slowly changing), and has a certain level of privilege within the academy. This privilege is grounded in the whitewashing of scholarship related to Buddhism and the systemic erasure of Asian Buddhists within convert Buddhist communities. Historically, non-Asian academics who studied Buddhism relied on Asian Buddhist informants and translators to carry out their research, and these contributions have gone largely unacknowledged and uncredited. As a result, in the US, scholars with academic degrees are presumed to have a more authoritative understanding of Buddhist traditions than the Asian people and communities who have performed the “physical, emotional, and spiritual labor” of maintaining these traditions for the last 2500 years.

The point, rather, is that Buddhist studies as a whole has failed to acknowledge systemic issues that need to be laid bare. Buddhist studies in the US is overwhelmingly white (and overwhelmingly male, although this is slowly changing), and has a certain level of privilege within the academy.

These issues within Buddhist studies are also linked to popular conceptions of Asian religious traditions more broadly, which are similarly informed by a colonialist past. Buddhism found its way to the so-called “west” by way of colonization, which has resulted in assumptions that Buddhism is universally applicable and transportable, and can be stripped from its “cultural” or “folk” aspects. This is often demonstrated by the comments I hear from seatmates on planes who, when I tell them what I do for a living, inform me that Buddhism is “more a way of life than a religion.” This kind of assumption that Buddhism is a universal wisdom tradition ignores its cultural history, and is yet another instance of Asian erasure.

Next Steps

Where do we go from here? Honestly, I don’t know. As a white person with a Ph.D. in Buddhist studies, this is a difficult issue to acknowledge, and I’m genuinely uncomfortable writing about this. My entire career is a direct result of the Orientalist assumptions and colonialist attitudes that I mention here, and acknowledging these issues calls my own status and privilege into question.

What I do know is this: we cannot proceed without a frank conversation about the privileges and problems of whiteness within Buddhist studies. This is not an issue with easy answers, and it is not a problem that can simply be solved by including more diverse scholars on our AAR panels. (Although that is something that we should be doing, as well!) As Mallory Nye puts it: “Decolonization is not about ‘finding space’ at the table: it is about changing the room.” It is long past time for Buddhist studies to begin rearranging our own furniture. It is only through acknowledging and confronting the colonialist history of our field that we can begin to change it. We must recognize the impact that our actions and attitudes as scholars have on the communities that we choose to study.

“scholars with academic degrees are presumed to have a more authoritative understanding of Buddhist traditions than the Asian people and communities who have performed the “physical, emotional, and spiritual labor” of maintaining these traditions for the last 2500 years.”

Does the author suggest that voices ‘from within’ are always more authentic and correct than scholarly analyses based on years of academic training? Should religion thus be taught by religious people (each teaching specific representations of what they consider ‘their own’ religion)? Is the emic/etic distinction also a relic from past Eurocentric studies?

“Buddhist studies, on the whole, has not acknowledged, let alone addressed, issues of colonization…”. At least for the last 50 years Orientalism and the ‘Protestantization of Buddhism’ have been issues integrated in the academic study of Buddhism.

My gratitude to the author for raising the concern: “We cannot proceed without a frank conversation about the privileges and problems of whiteness within Buddhist studies.” Many sincere followers and others who are unaware of being privileged will find this discomforting. But to be authentic, it is important to be humble and to seek to find out about our ‘self’ our ‘perspective’ and be life long learners. All of us benefit.

Thank you for speaking up and writing about this. I was born and raised as a Buddhist from Thailand. Practicing Buddhism in the US upsets me. It starts with the translation. Dukka is not just “suffering”. Metta is not just “loving-kindness”. We practice Buddhism in order to be resilient and survive the oppression, not just to “be happy”. Buddhism that most westerners are practcinging is colonized Buddhism. They only study it for less than 100 years. In Asia, it is in our blood and bones for 2,500 years. And yes! Buddhism is not a universal wisdom tradition. Thank you!

Thank you. My mother was converted to catholicism as a teen and I was raised catholic. My attempts to learn my ancestral practices/beliefs/values have always been mediated by white people who have taken up all the positions of leadership and first contact with people in my situation who colonialism has robbed of understanding/language/spiritual practice, vs. people who have learned it as a result of colonial extraction. It’s been a very challenging situation. Today I found a Buddhist community of my ethnicity and I can’t even begin to tell you how different and meaningful it was for me. And to then find this article and this comment…I am grateful.

What a surprise in America all the buddhist are not Asian. The Buddha’s teaching where meant for all who find value in them. If I go to Spain right now all the buddhist communities are spanish. It’s common sense that asians are a minority in the USA so for the religion to survive its going to have to attract the locals.