When Kamala Harris nominated Tim Walz for vice president, the New York Times ran a curious headline: “Harris’ Choice of Walz Over Shapiro Mollifies the Left but Misses a Chance to Reassure Jews.” As a headline (later slightly altered), it less reports on the news than it puts forward a telling chain of significations and oppositions. Why would Jewish voters need reassurance from Democrats? Are American Jews part of the left wing of the Democratic Party, or its opposition? What conflict is there between the Democratic Party’s left and the Jewish community? In short, in a sentence in which the opposition to “left” should be “right” or perhaps “center,” the word “Jew” has instead been substituted.

In his lecture “Old and New Identities,” Stuart Hall makes the observation that one has to be “positioned somewhere in order to speak” (72). The construction of identities is not only based in one’s history or communal belonging, but also in politics and ideology. Hall charts the decline of “class based” identities in the west and the decline of socialist movements alongside the rise of pan-African identities in the Caribbean such as “Blackness” as part of the global decolonial movements (75). In that new category, Hall suggests, he was called upon in his adulthood as very different kind of subject than he was in his youth in Jamaica.

Something rather similar, if also inverted, has been taking place within the category of “Jewishness” in the last several decades in the west. While “Jewishness,” at least since the advent of Christianity, has been constituted by a figural meaning beyond its halachic definition (which defines Jewish identity as being a member of the Jewish religion and/or a descendent of a Jewish mother), its meaning at least since the 19th century had been for a century rather stable. The Dreyfus Affair may be remembered as the beginning of modern political antisemitism; it is also marks one beginning of late 19th and early 20th century identity politics.

As historian Stephen Wilson pointed out, the Dreyfus trial was not immediately perceived as political. It was only after Emile Zola and several other prominent French intellectuals came out in defense of the Jewish artillery officer that socialist parties and liberals took up Dreyfus’s case as a cause. In response, the Right mobilized a populist campaign of anti-Jewish pogroms and street battles. As the French writer and socialite Baroness Steinheil commented, the trial “is no longer between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards, but between the Republic and enemies of the Republic, between radicals and socialists on one hand, and Royalists and ‘anti-Semites’ on the other” (102). That Dreyfus himself was neither a radical nor a reactionary mattered very little: he and his “identity” had been abstracted, or perhaps conscripted, into an ideology: “antisemitism” was now an explicitly political conflict, taken up by the Right and the Left on opposite sides, for the first time European history.

As is well known, the association of Jews and the Left long precedes Dreyfus, going at least as far back as the French Revolution. After the revolution, the new government recognized Jews as full citizens, a first for a European state. And of course, long after the Dreyfus Affair, Jews themselves embraced, if not liberalism, radicalism, with a large and vibrant Jewish presence in the American socialist and labor movements from late 19th century to the Cold War, along with over-representations of Jews in the Bolshevik Revolution and in left parties in South Africa, Argentina, and Brazil.

Indeed, after the Enlightenment began the dominant antisemitic image of the Jew was transformed from a Christ-killer to a secular revolutionary: one who bears the perversions of modernity, whether in the form of global capitalism or communism. According to Paul Hanebrink, the imagery of the Judeo-Bolshevik often simply translated Christian iconography of the Jewish devil to a secular force of social evil: for instance, in the anti-communist propaganda poster featuring a satanic, red-fleshed Leon Trotsky on top of a mountain of skulls. The Jewish financier and the Jewish communist both embody and concretize the abstractions of capitalism and state management together.

One can still see such lineages in the post-war United States. Jews who are less than two-percent of the U.S. population were nonetheless two-thirds of those questioned in the 1952 McCarthy hearings—to say nothing of the fate of the Rosenbergs. And of course, Marjorie Taylor Greene’s rantings about Rothschild space lasers and Tucker Carlson’s claim that George Soros finances migrant “invasions” into the U.S. are variants on this theme.

Since the early 1970s however, there has been a steady campaign led by key organizations in the putatively liberal Jewish establishment to remake the concept of antisemitism and by extension, Jewish identity. In 1974, Arnold Forster and Benjamin Epstein of the ADL issued its opening salvo in what would become a decades long attempt by the Jewish establishment to equate anti-Zionism with antisemitism. Their argument in the influential The New Antisemitism (1974) had two parts: the first, that Israel is “the collective Jew,” in Antony Lerman’s phrasing, a representative of the Jewish people concretized into a state. Rather than view Israel as a military power and client of the world’s first truly global hegemon, the United States, Israel was framed as a schlemiel among nations: a target for the unquenched rage the world still bares against Jews. And perhaps more insidious still, The New Antisemitism made a subtle but important substitution: the Jewish state was now a figure for the global Jewish people; indeed, the former subsumed the latter.

Rather than view Israel as a military power and client of the world’s first truly global hegemon, the United States, Israel was framed as a schlemiel among nations: a target for the unquenched rage the world still bares against Jews.

It’s important to note how much of a change the framing was: rather than understand the foundation of Israel as a conflict over land or geopolitical power, Forster and Epstein framed it as a question of Jewish identity. Israeli wars, including against the British, the 1948 and 1956 Arab-Israeli Wars, and the ethnic cleansing of Palestine’s indigenous inhabitants were historically framed as political questions over national identity, land, and citizenship. When Hannah Arendt wrote “Zionism Reconsidered” in 1944, she articulated the conflict as between the “Arab peoples” and European settlers—not antisemites against Jews (344). Likewise, there have been attempts by Netanyahu to retroactively blame Jerusalem’s grand mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini for the Holocaust. Such claims are not uttered because they are believable, but because they fit an uncomfortable past into a new framework.

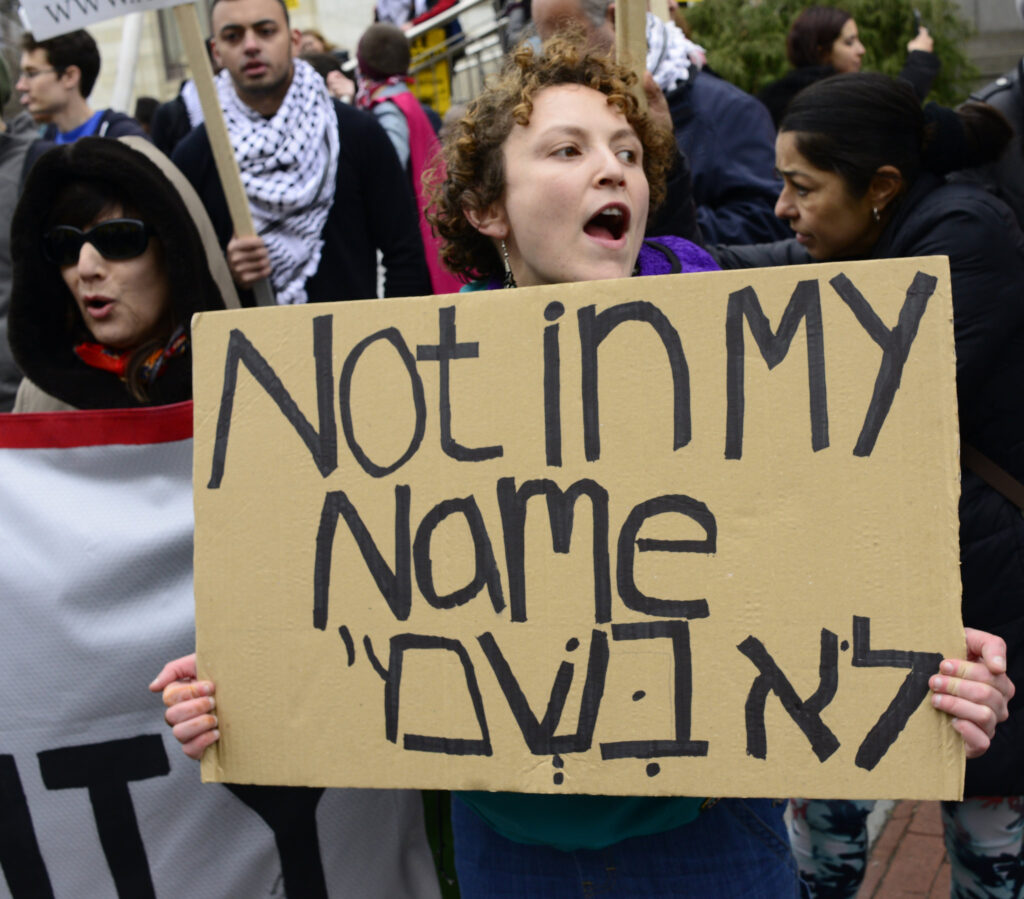

While the association of antisemitism and anti-Zionism is not new and is no longer news, with everyone from Jewish university presidents to anti-Zionist students to politicians and intellectuals smeared with the term for their criticism of Israel, such a construction has not only changed the discourse around Zionism, it has dramatically changed who and what is considered legibly Jewish, and thus what Jewishness has come to mean.

Perhaps most famously, the attack on Jeremy Corbyn while he was leader of the Labour Party in Britain not only targeted Corbyn as an antisemite, but also mobilized a new definition of Jewishness as a collective interest. This campaign denied Corbyn elected office; as importantly it reframed Jewish interest: Jews are supporters of the status quo and enemies of the Left. That this construction was primarily disseminated by non-Jewish activists and media personnel did not matter: the Jew as anti-communist and upholder of Western (neo)liberalism was complete.

This brings us back to Josh Shapiro. He was clearly not the first Jewish presidential or vice-presidential candidate to be denied his Party’s support. For example, in dramatic fashion, Bernie Sanders was denied by the Democratic Party establishment during the 2020 primary. Yet this did not raise concerns in the New York Times or among Democratic Jewish commentators such, as Eli Klein. One can neither argue that Sanders does not publicly identify as Jewish, nor that Sanders lacks his own loyal base of Jewish supporters, from “Jews for Sanders,” to the progressive Jewish magazine Jewish Currents, from IfNotNow to the Jewish caucus of the Democratic Socialists of America. This difference between the Jewishness of Sanders’s candidacy and Shapiro’s has less to do with who is more Jewish; it has a great deal to do with the way the idea of Jewishness has been constructed in the last few decades. Or perhaps, to channel Hall, how Jews have been positioned to speak.

Increasingly, media outlets from The New York Times to Fox News the New York Post have run stories on the defection of American Jews from the Democratic Party over the Democrats’ selection of Walz over Shapiro. In another headline on the topic, the NYT speaks of “heightened concerns” Jews have over the decision; the NYP states frankly that Jews are abandoning the Democrats for the GOP over Shapiro; Fox News reports that Walz is a “far left nightmare” for “Jewish organizations.” The assumption in all of these stories is not only that Jews care only about Israel, but also that Jews are a singular ethnic force of conservativism within the Democratic Party.

This difference between the Jewishness of Sanders’s candidacy and Shapiro’s has less to do with who is more Jewish; it has a great deal to do with the way the idea of Jewishness has been constructed in the last few decades.

A problem with this construction is that few American Jews seem to agree. Not only has the overwhelming Jewish identification with the Democratic Party remained stable as of April of 2024 according to Pew, the nomination of Tim Walz has been reported to be very popular among Jewish Minnesotans. Walz is also the vice presidential pick most aligned with mainstream American Jewish values, especially on reproductive rights, gun control, and an expanded welfare state. It also needs to be said that Israel is consistently ranked as a low priority among 96 percent of Jewish voters—behind climate change, the economy, antisemitism, and health care. And further, it is no secret that the consensus over Israel in the Jewish community has long since ended: one-third of American Jews believe Israel is committing genocide; 60 percent of American Jews believe that the Biden administration should embargo arms to Israel; over one quarter of American Jews see Israel as an apartheid state. If one selects for younger Jews, the number is closer to half.

And while it is arguable whether Walz is a “leftist,” what is of note is the way American Jews are deployed as wedge constituency by media outlets from the nominally liberal Times to the conservative Fox News and Post. This is an intensification, or perhaps a concretization, of the “The New Antisemitism” thesis. While Shapiro’s Zionism is far more virulent than Walz’s—he infamously likened Palestine solidarity protesters to the “Ku Klux Klan”—there is no suggestion that Walz is an anti-Zionist, let alone that he supports calls to embargo weapons for Israel. Thus Jews have gone from a constituency less formed by a support of Zionism, to a constituency marked by an ethno-conservativism. While the choice of Walz over Shapiro was overdetermined, it is clear that Walz was perceived as the more progressive of the two and was more suitable to the left wing of the Democratic Party. Any shift to the left in the Democratic Party is framed no longer simply as a threat to wealthy donors or tax cheats, but also to Jews as an entire people. In this reading, it is Walz’ s and Corbyn’s leftism that is more dangerous to the Jewish community than Boris Johnson or Donald Trump’s antisemitic conspiracy theories.

As Stuart Hall noted, the appearance of new social phenomenon is often less a case of novelty than a shift in the political conjuncture. A conjuncture, Hall reminds us, is a “specific life in a social formation” that forms a “unity” among disparate, even contradictory formations (368). The articulation of a new identity, or new social actor, often occurs when the social formation and its unwieldy set of unities is suddenly in crisis. Hall offers as an example the emergence of the “mugger” in the 1970s Anglophone Atlantic as a figure that hails the crisis of social democracy, and points to a solution of carceral neoliberalism. In a similar way, I would suggest, the emergence of the “Jewish conservative” has little to do with changing Jewish loyalties or allegiances, and everything to do with the crisis of both Zionism and neoliberalism.

Capital and imperialism cannot speak out of universal interest: they have none. Suggesting that the U.S. supports Israel’s genocide out of geopolitics—even identification with the state’s colonial project—can no longer be said by any liberal (anymore than it can be said that Shapiro was a better pick for the NYT and Post as much because of his Zionism as his support for school vouchers and his questioning of public health measures such as masking and vaccines). The consensus around Zionism and the kind of racial politics it supports—let alone the U.S. imperial presence in the Middle East—is rapidly fraying: constructing constituencies for which the state acts to protect is far more palatable than naked self-interest.

This is not to say of course, that there are no Jewish interests in Israel: major Jewish institutions from the ADL to the Jewish Federation have become more fiercely Zionist and right wing in the last few decades. Yet like Hall also reminds us, a crisis is not simply marked by systemic failure: it is also the detachment of the ruled from their rulers; it is the de-alignment of part of a hegemonic bloc from its formation and the potential realignment with another. We are in such a moment of crisis. Even in the stories by Fox and the NYT such discord is visible under the headline: after the ADL or Democratic Majority for Israel is quoted, IfNotNow and Bend the Arc are featured much further down in the story. What we are seeing in the Jewish community is not altogether different from what we are seeing in the U.S. writ large: a polarization around the fundamental question of whether we should live in authoritarian, racially bound states or in multi-ethnic democracies. While Jews may have their own internal fights within their institutions, in temples, community centers, and in the streets over Zionism and socialist politics, it is incumbent upon us to refuse such identitarian conscription as part of that fight.