Analogy is all I’ve ever really known. The only child of an Ashkenazi Jew and an African American, I’ve always experienced identification as coupled with recognition of difference. I have no experience of homogeneity to fall back on; even those closest to me are also unlike me in significant ways.

I am used to people thinking of me as a problem. My parents married less than five years after Loving v. Virginia guaranteed the legality of their union throughout the United States. As recently as when I was in college, I’ve been in discussions where the creation of “mixed” children was cited as a reason to avoid interracial relationships—because, the argument went, mixed children suffered a confusion so debilitating that it made their lives not worth living.

But I am not confused. What I am is confusing. In other words, the problem is not my sense of self or belonging, but the way that my very existence unsettles the carefully circumscribed categories that for so many people pass for reality. Even sophisticated treatments of identity fail to account for the possibility of people like me. For example, Aaron Hahn Tapper’s Judaisms: A Twenty-First-Century Introduction to Jews and Jewish Identities centers the diversity of Jews and Judaisms, but assigns Ashkenazi Jews and African Americans to non-overlapping categories. He remarks, “Ashkenazi Jews exist in terms of what they are not; they are not Jews of color” (21). But I am the descendant of “those Jews who trace their lineage back to Eastern European and Russian, Christian majority places” (19), and I am also the descendant of enslaved Africans. I do not shuttle between those identities like a child in a shared custody arrangement. I am always both of those things, at the same time.

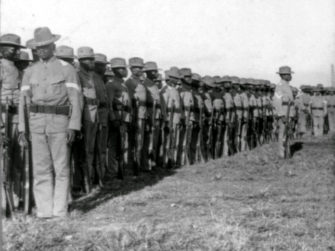

A focus on the purported confusion of the interracial person serves to maintain a problematic system for assigning identity by distracting from its failures. In a similar way, fixating on the problem of analogy can obscure the larger structural dynamics that govern the way that analogies function in the realm of identity. Because of the way in which acting literalizes the issues of representation and identification in play here, film can provide a helpful way to approach this subject. Consider the case of a controversy about a film’s casting of a White actor in a role that the original source material had identified as Asian. Framing the matter as a question of whether actors should only portray characters whose identity characteristics they share ignores the broader context that gives the matter its urgency. Whitewashing roles does not reflect a philosophical position about identity and acting. It reflects the strength of Hollywood’s preference for White actors. Because of this preference, a White actor can expect to play almost any character, while an Asian actor can’t even count on full consideration for a role originally imagined as Asian.

In a similar way, when it comes to racial justice, the problem of analogy is not so much a problem with analogy per se, as it is the problem of the preference for Whiteness. Whiteness is so deeply ingrained in US American culture as the baseline human experience that it functions as a kind of skeleton key that opens all doors. In that context, analogy stops being a way of making a connection between two experiences by highlighting their commonalities while acknowledging their differences. Instead, it becomes a kind of whitewashing, a way of overwriting one experience with another one that has more social capital.

Better analogies between Black and Jewish experience begin with decoupling Jewishness from Whiteness and acknowledging the Blackness within Jewishness. The reduction of Judaism to White Ashkenazic Judaism not only erases large numbers of Jewish people, but also neutralizes certain tendencies within Jewish tradition. As Lin-Manuel Miranda reclaimed Alexander Hamilton’s immigrant identity and its continuities with the experiences of contemporary immigrants to the USA, so a similar recognition is needed that white people are not the only legitimate heirs to and representatives of Jewish history and tradition. Many Jews became (sort of) White, but that doesn’t mean that the trajectory to Whiteness is the only arc though which Jewish history should be understood and invoked. When Jews move beyond American racial logic and view their tradition with a greater flexibility not constrained by the limits of Whiteness, the foundation has been laid for truly fruitful partnerships with all manner of groups.

Since the pandemic began I’ve spent more time with Birkot HaShachar (a Conservative version), and I’ve been struck by the depth of their correspondence to central themes in African American religion. African Americans have long turned to religion to counteract the experience of racism and cultivate another basis for identity, to be reminded, in the words of Beyoncé, “If you feel insignificant, you better think again…you’re part of something way bigger.” Through the blessings I acknowledge my interconnectedness with all creation, affirm the fullness of my humanity (or in contemporary terms, that my Black life matters), and embrace my God given freedom in the face of experiences that make me feel powerless.

The blessing that identifies God as the one who made me a Jew speaks to my experience of having my Jewishness called into question by people who don’t think I look the part. African Americans have historically gravitated toward modes of religious expression that emphasize a connection with God not mediated through Eurocentric authority, and to me, this blessing expresses such spiritual immediacy.

The blessing that invokes God as the one who clothes the naked employs imagery that has long captivated the African American religious imagination. In the Black Church, prayers frequently reference the gospel description of a man formerly possessed by a demon by offering thanks that one is “clothed and in [one’s] right mind” (Mark 5:15 KJV). Within the spontaneous prayer tradition of the Black Church, this language functions as part of a preliminary to prayers created in the moment, a regularized way of taking stock of the self and expressing gratitude to God. For me, the image of nakedness captures the vulnerability of being Black in the US and living under a constant threat of sanctioned violence.

In the blessing that invokes God as the one who releases those imprisoned, I hear the dismantling of mass incarceration. I also hear the possibility for metaphorical forms of release, such as from ideologies that imprison the mind, like the assumptions about race, gender, and work to which I all too easily succumb.

Then, when the once-crooked self stands upright, the blessings invite me to contemplate the cosmic power of God, a power that far exceeds those social structures that feel so all-encompassing, and that works toward a different end. In When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and asha bandele observe, “…the only plan for us, for Black people living in the United States—en masse, if not individually—is all tied up to the architecture of punishment and containment” (203–4). In contrast, the blessings affirm that mighty God with loving attention makes a way for us. Beyond the miracle of survival, the blessings remind me of my connection to powerful heritage and hope of overcoming and invite me to draw strength. The closing prayer to be seen, by God and people, through a gaze marked by grace, loyal lovingkindness, and compassion powerfully expresses my desire as a mother sending Black children out into a world in which their ordinary behavior might be coded as criminal and used to justify violence against them.

The prayer to be seen is also a prayer to be recognized and not defined out of existence or bracketed out of relevance. An important step in dismantling the unique form of oppression that is racism in the US is to transform the perception of the color line as an impenetrable barrier stretching across all of human existence. Race as we know it emerged in history. Neither God nor nature assigned each person a place in a discrete, homogenous group. The limitations of making analogies between groups are just as relevant to the process of designating groups as such. Even those who share Blackness or Jewishness, for example, share them differently, including by sharing both at the same time. In the end, it is all analogy.