The weaponization of “Islam,” imagined as an inevitable and immutable cause for violence and social disruption, is a recurring global phenomena that is employed by numerous national bodies. For example, in 2020 alone, we saw Muslims in France being deemed unsuitable citizens based on the criteria of French laïcité, and in India there were religious conversion laws that criminalized Muslims in interfaith marriages and the Citizenship Amendment Act that disadvantaged Muslim refugees. This pattern of state-administered harm against Muslims in China can be seen so clearly in the ongoing Uyghur crisis because it is severely protracted and especially monstrous. While the Uyghur crisis doesn’t revolve solely around Islamic identity and practice, the category “religion” provides an organizing framework that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) utilizes to justify its continued oppression of the community. The historical expansion into Uyghur lands through settler colonialism and the continual denial of Uyghur sovereignty by ruling bodies has drastically intensified under General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping through practices of technological surveillance, invasion of private spaces, mass detention, incarceration, and internment. Across these perilous circumstances, the insistence on a clear distinction between religious and secular domains of social life undergirds the CCP’s governance of Uyghur life.

Regulating Religion in China

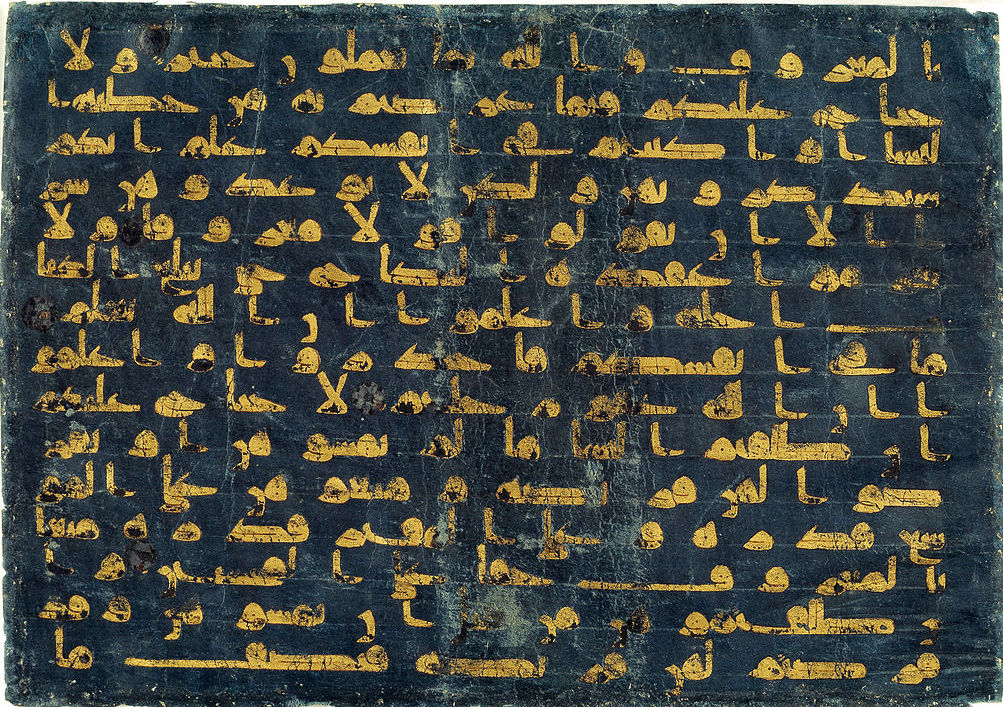

Since the People’s Republic of China operates as an authoritarian secular state, whose party members are obligated to renounce religious belief, it has established its ability to govern religion. The privilege of religious freedom is set out in the constitution but is limited to religious belief and only offered to recognized groups, including the five official religions of Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Daoism. The discursive construction and legal definition of religion hinges on European Christian understandings of the category, which prioritize faith over and above practice. China’s safeguarding of religion did not include lived social behaviors and proselytization associated with a tradition. In 1982, Article 36 of the Constitution of the PRC established that “[t]he state protects normal religious activities. No one may make use of religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state.” What is deemed “normal” was governed by the state through the Religious Affairs Bureau, also known as the State Administration for Religious Affairs. In 2018, however, this department was absorbed into the United Front Work Department, which reports directly to the Chinese Communist Party. The state has the ability to regulate what it deems appropriate “religion” in matters of worship and practice, professional leadership, and sacred institutions.

While the Uyghur crisis doesn’t revolve solely around Islamic identity and practice, the category “religion” provides an organizing framework that the People’s Republic of China utilizes to justify its continued oppression of the community.

Since Islam is an officially recognized religion, the Chinese state can govern what the tradition looks like in word and practice for Muslims living in the country. The specifics of what counts as official Islam in the PRC were first set and circulated through the China Islamic Association, founded in 1953, which is made up of leadership that is affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party. The vast majority of Uyghurs are Muslims so the state’s ability to regulate Islam directly shapes Uyghur religious life, which the state has increasingly posited as being in opposition to being a Chinese citizen. The state has operationalized “Islam” as a signifier of potential state disruption and treated Muslims with force, dominance, and discipline. But the state’s reliance on a discourse of acceptable and unacceptable religion has played a shifting role in classifying and regulating Uyghur life.

Historically, Muslims across China have had changing relationships with one another. At times, Muslim communities have been in direct conflict with other Muslim groups, or aided in state domination of other Muslim populations. For example, Sino-Muslim communities (i.e. Hui minzu of the PRC) had both internal conflicts based on religious leadership or ritual difference, and have also had tense relationships with Uyghur Muslims. During other moments, Hui and Uyghur Muslim worked and lived together, even in opposition to state control. James Millward’s expansive Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang paints the most comprehensive picture of the history of the region. In 1759, during the Qing dynasty’s colonial expansion to the west, the Qianlong Emperor annexed what was dubbed Xinjiang (New Domain or Frontier), the region many Uyghurs call East Turkistan today. The grand swath of land under Qing rule during the 18th through early 20th century was made up of a great deal of ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity. Qing leaders employed strategies that fostered greater autonomy within local communities across various cultural regions but maintained control by accommodating diversity among their subjects. This “imperial pluralism,” as Millward puts it, was echoed during the 20th century through the minzu system (usually rendered nationality or ethnic group), which designated 56 minzu groups (including the Han majority) who had equal standing as Chinese citizens.

Indigeneity, Separatism, and Settler Colonialism

The minzu question, or the question of how the state relates to its minorities, has been one way scholars have tried to understand contemporary Uyghurs. However, under the PRC’s control there was increased promotion of settler colonialism in East Turkistan, where Han Chinese have been inching closer to being equal in number to the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. While the Uyghur question is often framed as an issue of minority suppression, we should remember that it is also one of indigeneity. Uyghurs, like Mongols and Tibetans, are a majority population tethered to specific geographies that have been encroached upon by outsiders and the community has been socially and politically stifled within their indigenous lands. In 1953, Han settlers stood at 6% of the overall Xinjiang population while Uyghurs made up 75%. The settler colonialism framework helps us render the logics of resistance within a more suitable domain than the minzu paradigm since the Uyghurs were not a minority but were minoritized.

In periods of Uyghur unrest during the second half of the twentieth century, the state commonly used a discourse of “separatism” to describe Uyghur resistance to the government’s policies. However, social turmoil was most often the result of a search for greater Uyghur autonomy within their indigenous lands rather than a plot for secession. The state continued the separatism classification especially within the context of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the creation of newly formed Central Asian nations. During this period, “religion” was not a generative discourse for advancing state suppression of dissidents and, therefore, was generally ignored in state documents and statements. This strategy was effective until the CCP found a new fertile slogan for drumming up international support for their domestic Uyghur difficulties: the “War on Terror.”

Islam and Terrorism

The attacks on September 11, 2001 catalyzed a series of new policies, governmental departments, and ideological positions in the United States. The logic of the so-called “War on Terror” relied on the circulation of long held representational stereotypes about Islam in US popular media, governmental knowledge production, and colonial encounters with global Muslims communities, as well as the inherited traditions about the “Orient” from European predecessors. The lynchpin of arguments for state anti-Muslim suspicion and conduct was rooted in essentialized interpretations of Islam that suggested an inherent Muslim disposition towards defiance, resistance, and violence. Talal Asad argues that these types of assumptions about the essential violent features of “religion,” as opposed to the seemingly justifiable logic behind “secular” aggression and force, pivot on the construction of these two categories as separate and unique.

The US policy tendency to equate Muslims with potential terrorist threats was soon wrapped up in international diplomatic exchanges and agreements, incorporating opportunistic governments wishing to control Muslim communities more restrictively through the global “war on terror” and its logic of racialization. The CCP moved the classification of their Uyghur anxieties from a “separatist” to “terrorist” designation that is directly tied to notions of “religious extremism.” This rebranding of China’s domestic tensions was validated when the U.S. government added the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) to the U.S. terror list. Sean Roberts new book, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority, exposes the fallacies behind the CCP’s claim of a local “terrorist threat” while also illustrating the broader historical, political, and social contexts in which the discursive shift in Chinese discourse took place. In October of 2020, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo removed ETIM from the U.S. terror list but the initial international endorsement already set things in motion. The cover of the “War on Terror” allowed the CCP to exercise its suppression of any Uyghur resistance to state policies under the guise of the global battle against “religious extremism.”

Religious Extremism and the Criminalization of Islam

Following the CCP’s label modification we can see how the form of the policies and the shape of their enforcement have changed over time. Over the past decade, many restrictions seem directly related to what would be popularly understood as “religion.” For example, in 2014 we saw the exclusion of traditional Islamic sartorial markers through a local ban on the “five abnormal appearances,” which included women wearing niqab, hijab, or burqa; clothing with crescent moon and stars; and long beards for men. The use of “religious” evidence as means for suspicion ramped up after 2016 with the appointment of the new leadership of Chen Quanguo as Communist Party Secretary for the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. After piloting techniques of social control in Tibet for 5 years, Chen set up the security architecture that we have become so familiar with in the region’s recent history, including surveillance systems with QR codes, eye scans, smartphone access, blocking of external media sources, and re-education programs. The tactics explicitly associated with Islam ramped up shortly after Chen took control and were classified as indicators of “religious extremism.” The signifiers included things like going on pilgrimage to Mecca, traveling to Muslim majority countries (such as Turkey, Egypt, and Indonesia), closing a restaurant during Ramadan, exchanging Islamic greetings, wearing a headscarf, or having a long beard. These types of activities could land you in an internment camp for re-education, according to CCP policy. The working assumption is that strong religious participation meant an inclination to follow extreme forms of Islam, which from the party’s perspective meant that they were predisposed to violent disruption of the state.

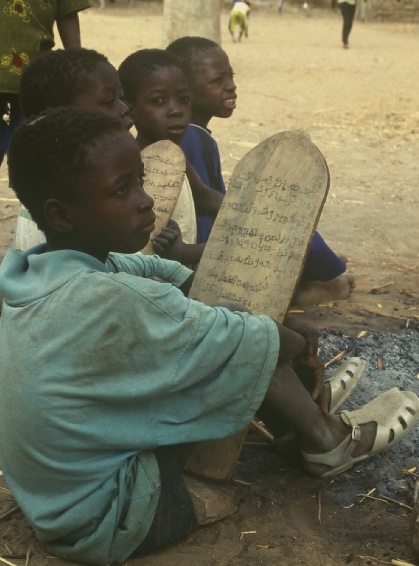

Another factor here is the structure of state-recognized religions and how “official” religion is able to operate. Fenggang Yang’s model for understanding the regulation of religion in China today organizes traditions into “a red market (officially permitted religions), a black market (officially banned religions), and a gray market (religions with an ambiguous legal/illegal status)” (93). Much of Uyghur religious practice is related to the gray market because while Islam is officially sanctioned, non-institutional practices and holy places are deemed illegal. The state has gone after these holy places recently, closing or destroying mazars (shrines or mausoleums) and razing grave sites, both of which play central roles in Uyghur religious life. Official Islamic sites have also been targeted with mosques being torn down or significantly altered in dramatic ways. These religious markets also reflect the reality of practices concerning religious education, the circulation of Islamic texts or videos, the preaching of religious knowledge, or attending religious gatherings, all of which are seen as illegal behavior that is indicative of extremism. The state views these religious expressions as evidence of cultural backwardness or infectious ideological illness that need to be rectified through re-education. But for many Uyghurs, a rigid distinction between what is deemed “religion” versus “culture” defies their lived experience where common everyday social practices intersect with their local exercise of Islam. How one dresses, eats, greets one another, treats their family members, celebrates life, buries their dead are all shaped by a rich social history that is infused with vernacular customs inspired by Islam. To deny the right to carry out this way of life, as it is rendered “illegal religious extremism” by the state, is to deny Uyghurs of their distinctive heritage.

The Uyghur Crisis between Secularism and Religion

The shift in state policy from a multicultural and ethnically diverse sense of Chinese citizenship (echoing the imperial pluralism of earlier settler colonization) to the assimilationist approaches of Xi’s regime, characterized by Han-centric ethno-nationalism, leaves very little room for Uyghurs. National homogeneity requires cultural capitulation and the surrender of ethnic or religious difference. Or as Rachel Harris has pointed out, the government uses “Uyghur heritage as a cultural resource to develop the tourism industry” through narrowly defined cultural expressions and kitschy spectacles of sound and color. To be Uyghur under the current state vision of what national subjectivity looks like is inherently disruptive. The very presence of Uyghurs serves as a reminder of resistance to state power, which prompts the CCP to develop management strategies that regulate ethnically diverse populations. From the state’s perspective, relinquishing Islam will sever Uyghurs’ ties to “extremist” stimuli and allow them to be productive Chinese citizens. However, this position rests on the assumption that “religious” and “secular” behaviors, traits, and characteristics are neatly divided and do not intersect. This, of course, is a myth. While it is not the only factor that shapes the current Uyghurs crisis, one cannot fully understand this emergency outside of the framework of the study of religion, secularism, and modernity.

The cover of the “War on Terror” allowed the CCP to exercise its suppression of any Uyghur resistance to state policies under the guise of the global battle against “religious extremism.”

As Talal Asad reminds us in his most recent book, Secular Translations, “The terms ‘secularity’ and ‘religion’ belong to what Wittgenstein called language games, games within which consensus and dispute occur as part of ordinary life—games that are always capable of being changed, with or without agreement” (148). We witness this language game in the discursive shifts that have occurred in CCP word play over the past two decades in regards to the Uyghurs. The state has operationalized “religion” as evidence of the potential for social disruption, which it has combatted through the systematic governance and regulation of ordinary Uyghur life. It has changed the rules of the game for how it justifies its own violent and oppressive measures that directly affect Uyghur culture and identity. As outside observers, we should stay attuned to the moves but not get lost in the play because this is a game that Uyghurs cannot afford to lose. As many have noted, the current trajectory of events could best be described as cultural genocide, where Uyghurs have been depopulated and displaced in their homeland, stripped of their language and cultural practices, had their histories and stories erased and banned, their religious observance criminalized, and their families and friends disappeared. We should continue to support efforts to address the Uyghur crisis as a critical humanitarian issue that requires an international coalition standing up for the community.