These are incredibly difficult times for many—including those in academic institutions dealing with a number of battles on multiple fronts—and so, I begin my response by recognizing the intellectual labor of my colleagues Ather Zia, Amen Jaffer, and Matthew Shutzer for their time and incredible engagement with my book, as well as Josh Lupo and Atalia Omer at Contending Modernities for hosting this forum.

Colonizing Kashmir touches upon a number of themes—including state-formation, state-building, decolonization, developmentalism, “post” colonial state sovereignty, secularism, and the politics of life—and I am thrilled that the responses to the book cover these multiple themes. To begin, I would like to underscore that the primary aim in writing the book was to analytically parse out how values that are seen as having a “positive” valence, such as state-building, democracy, development, and secularism (inherent to the liberal political order) are often weapons of colonial occupation and the denial of self-determination for nations and indigenous communities around the world. While this argument certainly has been made for European colonial powers, there is little scholarly engagement with how the postcolonial nation state draws upon the legacies of European colonial rule, but then produces its own colonial logics as well. In the book, I show how settler colonialism, colonialism, and occupation are all important frameworks to understand India’s relationship with Kashmir. In this response, I take up the themes of autonomy, the politics of life, and the relationship between sovereignty and settler-colonialism that my interlocutors pushed me to consider further.

The Illusion of “Autonomy”

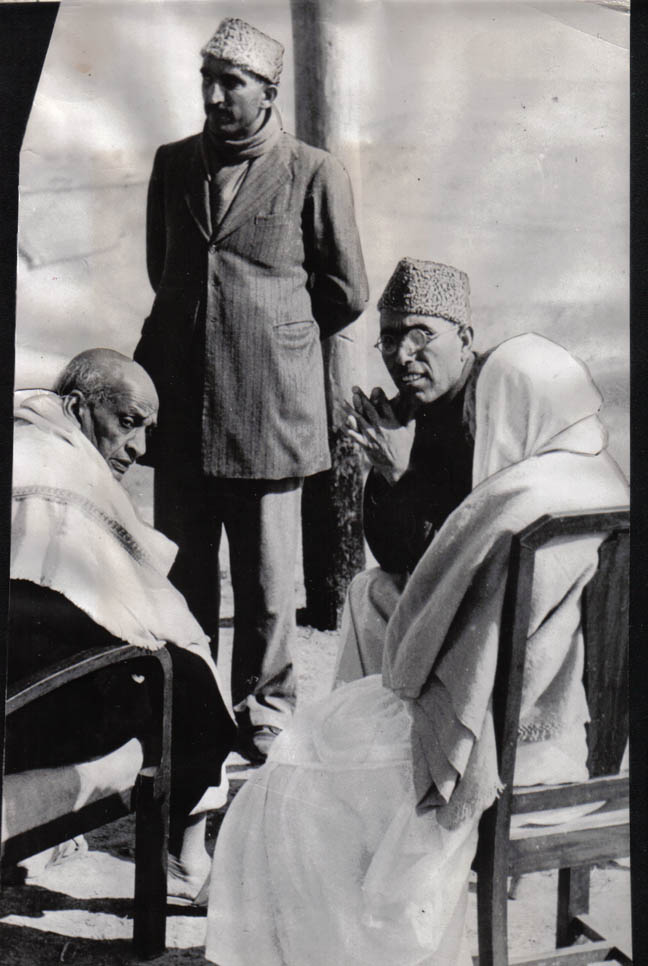

The question of autonomy is an interesting example of how something that is seen as having a positive valence, is in effect, a method of colonial control. As Ather Zia details in her response, even though Kashmir’s client regimes saw Article 370, which created a special-status for the state under the Indian Union, as an “ironclad safeguard for self-rule and territorial sovereignty,” it was in fact, a “death knell for their sovereignty and self-determination.” The promise of autonomy by India’s leadership—and specifically by Jawaharlal Nehru—was deployed as a mechanism to generate support amongst Kashmir’s political leadership (including figures like Sheikh Abdullah) to give their backing to Kashmir’s contested accession to the Indian government. Once in power, however, the Indian government was able to evade Article 370 by passing a series of presidential orders that chipped away at Kashmir’s autonomy. The presence of “autonomy” for the J&K state via Article 370 is sometimes interpreted as a negation of the settler colonial logic, especially given that this autonomy did not allow Indian citizens to buy land or property in Kashmir: this was restricted to Kashmir permanent residents. The question that is often asked then is: how can the state be (settler) colonial if it is promising autonomy or not taking or grabbing land? As my book and other scholars have argued, the promise of autonomy by the Indian government was perceived as a temporary measure until the political situation was stable in Kashmir—the plan (delayed by the internationalization of the issue, Pakistan’s role, and Kashmiri resistance) was always to fully annex Kashmir and incorporate it into the Indian union. The “granting” of certain concessions by the Indian state, thus, should not be seen as a negation of (settler) colonial rule. Settler-colonial logics that lay claim to the land can be in operation even if settler-colonial dispossession is not as visible. The state is also responding to other factors. For example, in this moment, there was a reputational cost as well, since India depicted itself as the vanguard of the third world, and an ally of other anti-colonial nations fighting for their freedom.

But there is an additional point to be made here. The book argues that India’s rule in Kashmir did not rely on direct eliminationist strategies (driving people off the land), but rather, assimilationist strategies in the period in the aftermath of Partition. It was elimination by assimilation. Indian secularism—informed by Brahmanical geographical logics—saw Kashmir as integral to the idea of India. The perspective of figures like Nehru, as well as Kashmir’s client regimes, was that Kashmir’s Muslim identity (which they represented as being influenced by the tolerance of its Hindu traditions, and thus, unlike the Islam practiced in Pakistan) could be tamed and be a part of India’s secularism. This secularism, however, still maintained that Kashmir was Hindu land and that its original inhabitants were Hindu. It is precisely through this erasure or taming of Islam—and Kashmir’s Muslimness—that the settler colonial assimilationist logic plays out, laying claim to exclusive constructions of Hindu indigeneity. Furthermore, integrating Kashmiri Muslims by showing them the benefits of being under Indian rule, and thus securing Kashmir for India, was an aim of both the Indian government and Kashmir’s client regimes. I appreciate Amen Jaffer’s observation on this point that this form of selective erasure as “a model of cultural appropriation points to some key differences between colonial governmentality in Kashmir and Orientalist approaches to the colonization of culture.”

It is precisely through this erasure or taming of Islam—and Kashmir’s Muslimness—that the settler colonial assimilationist logic plays out, laying claim to exclusive constructions of Hindu indigeneity.

It is precisely the diversity of the modalities of rule that the Indian government used to hold on to Kashmir in the 1950s and 1960s that the book highlights. And because some of these policies appear to be of “benefit” to the people of Kashmir (construction of schools, tunnels, grants, cultural festivals) they are not seen as being inherently colonial. Yet, my book examines how these acts of colonial benevolence undermined Kashmiri agency and sovereignty—they were actually not for the people’s betterment. For example, the curriculum in schools and the kind of cultural production that was sponsored relied on a very selective reading of Kashmir’s history that justified its incorporation into the Indian union. Infrastructure projects like tunnels were constructed to further emotional and material integration between Kashmir and the Indian mainland. In essence, as Zia notes, “hallmarks of modernity, especially infrastructure, literacy, and development—which Kashmiris badly need—were used to manufacture compliance.”

The Politics of Life

All of these cohered around the “politics of life” which “entailed foregrounding the day-to-day concerns of employment, food, education, and provision of basic services” while suppressing questions of self-determination and Kashmir’s political future (9). In the book, I highlight how this happened in the realm of economic development, media, education, rice subsidization, and culture. But it was also directed towards Indian and international audiences through propaganda, film, and tourism. Amen Jaffer, in his thoughtful response, asks how this “plethora of policies and projects…coalesce around the category of the ‘politics of life?’” In particular, he asks if we can think about state propaganda for foreign audiences as part of the “politics of life” framework as well? This is an important question, and one I could have certainly developed a bit further in order to sharpen the theoretical framework of the politics of life. Here, I will address this question in brief: the politics of life was premised on a colonial notion of progress—that the “backwards” Kashmiris could progress under Indian rule, and as they did so, they would be in favor of that rule. The propaganda that was conducted for international audiences was grounded in the notion that India was helping Kashmir prosper—and it solely could allow it to prosper. This is why much of the propaganda contained information about all the ways Kashmir had “developed” under Indian rule. Ultimately, this could only happen under “secular” India—a nation that was committed to progress and modernity, in contrast with its “theocratic” neighbor, Pakistan (which was ostensibly the other option for Kashmir in relation to the UN mandated plebiscite).

The politics of life was premised on a colonial notion of progress—that the “backwards” Kashmiris could progress under Indian rule, and as they did so, they would be in favor of that rule.

Jaffer also asks what might be the potentials and limitations of thinking with the politics of life as a mode of colonialism. One potential limitation that I can see is that some may assume it locates all forms of state-building or the “care and administration of life” across diverse political contexts as being colonial. That was certainly not my intention. It is important to situate the politics of life alongside the denial of sovereignty or self-determination. It is one tool—of many—that the colonial state utilizes in different moments (in addition to extraction, racialization, or genocidal violence).

What I argue is particularly sinister about the politics of life, however, relates to one of the pathways Jaffer points to in relation to extending the analytic frame of the book, which is that it primarily focuses on how power shapes subjectivities, and the ways in which subjects themselves respond is not clear. What is missing, Jaffer observes, is an account of “how these policies were debated, made sense of, acted upon, and even appropriated for their ends by the Kashmiri people” and how that “can open avenues for understanding the limitations of the Bakshi colonial project as well as offer insights into how it was actively resisted or channeled into unplanned directions.” I sought to do this in my chapter on cultural reform, and specifically Bakshi’s patronage of Kashmiri artists and writers. I argue that despite these artists serving in some bureaucratic capacity under the state government, many of them, in their poetry, short stories, or other writings, contested the notion of “progress” that was being propagated during their day jobs. As I’ve written about in a separate, but related article, many Kashmiris at this time had to negotiate their desire for economic and social mobility with their political aspirations—as a result, as I note in the conclusion, they were (and continue to be) marked both by resistance to and collaboration with the same colonial structures.

But there is certainly more that can be said on this important point. For the “response” to these policies, we can also look at the mid 1960s (a period right after Bakshi’s rule ended), where student movements rose in Kashmir, combined with the massive protests after the Holy Relic Incident, that culminated into mass mobilizations against Indian sovereignty. As Jaffer asks, “Why was it that despite significant material improvements for Kashmiri Muslims and their widespread recognition of Bakshi’s authority and his policies, they ultimately rejected the Kashmiri state and refused to diminish their demands for self-determination?”

It is important to situate the politics of life alongside the denial of sovereignty or self-determination. It is one tool—of many—that the colonial state utilizes in different moments (in addition to extraction, racialization, or genocidal violence).

I think the answer to this question lies in the contradictions of these state-policies, but also, brings us to an important point about how (settler) colonial rule will always be resisted, despite the varying modalities of rule through which it operates. As J. Kehaulani Kauanui argues, indigeneity endures—people continue to “exist, resist and persist.”

Sovereignty and Settler Colonialism

But part of the answer to this question is also linked to a point Matthew Shutzer makes in his response. Discussing Sahana Ghosh’s work, he argues that we can see “the border and its surveillance regime as an infrastructure for incompletely attempting to sever the intimate and material connections that routinely transcend geopolitical boundaries.” It is in this incompleteness—the traces of those connections that transcend—that we can see why this state-building project did not succeed in emotionally integrating Kashmiris. In my future work, I hope to better explore this transcendence through an examination of the role of Islam and Muslimness in shaping Kashmiri political aspirations.

The question of the subterranean opens up another avenue of exploration in the context of Kashmir, and I am thankful to Matthew Shutzer for highlighting this point in relation to his important study on coal and mining industries in central and east India. As Ather Zia notes, the post-2019 moment has led to greater attempts at economic extraction by the Indian government, including of Kashmir’s mineral reserves through a similar political corporate nexus as in the central/eastern mining belt. While my research attends to the specificity of Kashmir, I am also interested in thinking through how we can understand Indian state-formation occurring in other contexts, in places like Hyderabad, the Northeast, Punjab, as well as Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Here, I am interested in thinking through the sovereign right to land that Shutzer examines in relation to (settler) colonial modalities of power. I appreciate his evocation of the aporetic sovereignty, where “sovereignty is not a settled discursive form…but is itself an active practice often made through both the utterances of the law, and its everyday and routine silences.” Where this coherence cannot form (perhaps due to the transcendence mentioned above), “relations of power are instantiated and sustained, often violence, on-the-ground.”

The archival context that Matthew Shutzer provides further highlights the point made earlier about how the politics of life plays out in the context of Indian state-formation. For it is not just the Kashmiri that is in need of Indian state benevolence, but it is the “primitive” Adivasi as well. As he highlights, it is a discourse that “fancifully imagines social integration while seeking to enact the most brutal forms of displacement and dispossession that undermine those conditions of possibility.”

Can we then understand the Indian state as a settler-colonial entity across these varied geographies? What geographic and ideological imaginaries underpin Indian state sovereignty? I hope the book opens up these conversations for contexts beyond Kashmir, in addition to other similar politically liminal sites. The Kashmir case allows us to question not just the displacement and dispossession, but the fanciful imaginary of integration into the nation-state form as well.