This essay is based on a talk given during the “Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Critique of Israel: Towards a Constructive Debate” conference held at University of Zurich from June 29–30, 2022.

To confront the relationship between antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and the critique of Israel is a daunting challenge. In light of this monumental task, a remark from the Talmud comes to mind. Rabbi Tarfon said, “The day is short, the task is great. You are not obliged to complete the task, but neither are you free to give it up” (Bab. Tal., Ninth Tractate Avot, 2:20–21). This sums up my situation perfectly. My space is limited and the task is great. I could not possibly complete it, but neither am I capable of giving it up. Far from giving it up, the question of the Jewish Question is now at the center of my work on antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and the critique of Israel.

This post is divided into two parts. In part I, “Asking the Jewish Question,” I argue for one reading of the Question. I call it, for a reason that I hope becomes clear, “the antithesis reading.” In Part II, “Questioning the Zionist Answer,” I concentrate on an alternative reading, “the national reading,” which I see as underlying political Zionism in all its different forms. (In this essay, whenever I refer to Zionism I mean political Zionism and not the cultural Zionism associated, in the first place, with Ahad Ha’am.) There are many angles of approach to questioning Zionism. In Part II, I refer only to “the postcolonial critique” advanced by the Left —but I barely scratch the surface. (Barely scratching the surface is a good way to describe my essay as a whole.) I argue that, on the one hand, Jews who react against anti-Zionism (or come to the defense of Israel) tend to slip unawares between one reading of the Jewish Question and the other. On the other hand, the Left (including a section of the Jewish Left) tends to be too quick to dismiss their reaction when giving a postcolonial critique of Zionism and Israel. The combination of these two tendencies generates impassioned confusion—confusion that is not merely intellectual—on both sides. The analysis points to self-critique—on both sides—as a condition for the possibility of constructive debate.

I. Asking the Jewish Question

The so-called “Jewish Question” is a question in the sense of being a problem that needs to be solved. But who set the problem? For whom—in whose eyes—is there a problem about the Jews, the Jews as Jews? I suppose the first person who saw the Jews as a problem was Moses, who, time and again, complained to God about them; or maybe it was God who first saw the Jews as problematic. I don’t know. In any case, the problem they saw is not exactly the problem to which the so-called “Jewish Question” refers. The “Jewish Problem” is set by Europe: it is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews.

The term “the Jewish Question” became current in the 19th century. This was, says Holly Case in her book of the same name, “the age of questions,” by which she means questions with the form “the X question.” The X questions were a motley lot, but, by and large, they could be grouped under three headings: “social,” “religious,” or “national.” The Jewish Question, rather like the Jews themselves, had no fixed abode: it could be housed under any one of these headings. I shall focus on the view that, au fond, it was a national question, keeping company with such questions as the Armenian, Macedonian, Irish, Belgian, Kurdish, and so on. I do so because the national take on the Jewish Question is the one that is especially relevant to our conference, “Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Critique of Israel: Towards a Constructive Debate.” From Herzl to the present day, the Jewish Question has been construed in political Zionism as a national question; and Zionism lies at the heart of the current debate about Israel and antisemitism.

The “Jewish Problem” is set by Europe: it is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews.

The national take, however, is a mis-take. The Jews were not another case of a European nation whose future on the political map was the subject of debate. Rather, whether the Jews collectively are a nation in the modern (European) sense was up for debate: it was an integral part of the Jewish Question. Nor was there anything novel about querying their collective status: the status of the Jews was seen as problematic for a thousand years or more before the political formations that were the subject of the National Question in the 19th century came into being. And, while there were other groups in this period whose status as nations was up for debate, the case of the Jews was radically different. How so? The answer to this question gets to the core of the Jewish question.

I noted earlier that the Jewish Question is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews. But, although ostensibly about the Jews, ultimately it is about Europe: it is about Europe via the question of the Jews. It always has been, ever since antiquity and the days of the original European Union (as it were), the one whose capital city was Rome. Anti-Jewish animus is older than the Roman Empire, of course. But the story I have in mind begins with the conversion to Christianity of Flavius Valerius Constantinus, otherwise known as Constantine the Great, Emperor of Rome. Constantine’s conversion on his deathbed gave birth, in a way, to the question that came to be called “Jewish.” From this point on, Europe has used the Jews to define itself. The question, which we might rename “the European Question,” was this: What is Europe? Answer: not Jewish. Down the centuries, as Europe’s idea of itself changed, this “not” persisted, though it took different forms.

Granted, in the “New Europe” that emerged after the shock and tumult of the Shoah and the Second World War, the role of Jews collectively has, to some extent, been inverted. We are now liable to function for Europe (as I have discussed elsewhere) more as an admired model than as a despised foil, with consequences for Western European policies towards the State of Israel. Furthermore, a thread of philosemitism runs through Europe’s history. Neither of these points, however, contradicts the account I am giving here of the negative role played by Jews down the centuries in Europe’s self-definition.

Thus, the Jewish Question existed as an issue for Europe avant la lettre. Seen as being in Europe but not of Europe, the Jews were the original “internal Other,” the inner alien to the European self, the Them inside the Us. First, in antiquity, Judaism was the foil against which Europe defined itself as Christian. Then, in the eighteenth century, the Jews were, as Adam Sutcliffe puts it in his book Judaism and the Enlightenment, “the Enlightenment’s primary unassimilable Other,” but no longer as the immovable object to Christianity ‘s irresistible force (254). Esther Romeyn explains: “For the Enlightenment, with its investment in universalism and civilization, the Jew was a symbol of particularism, a backward-looking, pre-modern tribal culture of outmoded customs and religious tutelage” (92). In the following century, the symbol flipped. Romeyn again (partly quoting Sarah Hammerschlag): “For a nationalism based on roots, the distinctiveness of cultures, and allegiance to a shared past, the Jew was an uprooted nomad or a suspect ‘cosmopolitan’ aligned with ‘abstract reason rather than roots and tradition’” (92; Hammerschlag, 7, 20). Europe now saw itself as a patchwork quilt of ethnic nationalities and the question arose: “How do the Jews fit in? Do they fit in? If they do not, what is to be done with them or with their Jewishness?” This was the Jewish Question in the 19th century, a new variation on a very old European theme: the theme of the anomalous Jew; or, more precisely, the antithetical Jew.

In short, the National Question was about ethnic difference and how Europe should deal with it. The Jewish Question was about the alien within—so deep within as to be internal to Europe’s idea of itself. Other groups and peoples, such as Arabs and Africans, have played the part of Europe’s external Others; this is written into the script of European imperialism and colonialism. They too have provided a reference point for Europe to define itself by way of what it is not. But Jews as Jews are not part of the colonial script. As Jews, we have been, ab initio, “insider outsiders,” a people who, in any given era, are the negative—the internal negative—to Europe’s positive: belonging in Europe by not belonging. Certainly, the Jewish Question, as it has been asked in different European places at different times, has features in common with other “X questions.” Moreover, the Jewish Question is not unique in being unique! Each “X question” is unique or singular in its own distinctive way. But the singularity of the Jewish case is such that it escapes the boxes in which other “X questions” are placed. Being seen as antithetical to Europe, like the alien race in the 1960 horror film Village of the Damned: this is what underlies the questionableness of “the Jews.” It is why (to allude to the title of my paper) the Jewish Question is different from all similar questions. I call this reading of the Jewish Question “the antithesis reading.” Whether it adequately describes the Jewish space in the European imagination, the salient point is this: this is how the Question sits in Jewish collective memory, continually working in the background of the Zionist answer to the Question.

II. Questioning the Zionist Answer

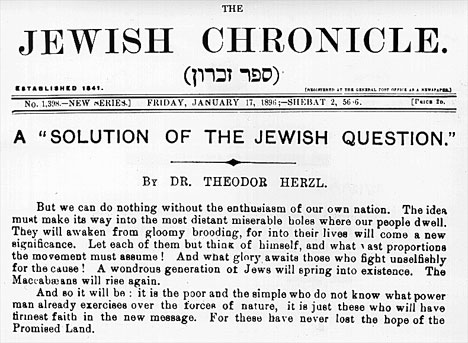

The mass of Jews, if only subliminally, bring collective memory to their embrace of Zionism and the State of Israel. They keep slipping, in the process, between two different readings of the Jewish Question, eliding the one with the other: the one I have just given and the one that Theodor Herzl gives in Der Judenstaat. Herzl’s (mis)reading has become a staple of the State of Israel as it defines itself (and, simultaneously, defines the Jewish people). In Der Judenstaat, he fastens onto the category of “nation.” He writes: “I think the Jewish question is no more a social than a religious one, notwithstanding that it sometimes takes these and other forms. It is a national question …” (15). The subtitle of Der Judenstaat calls his political proposal, a state of the Jews, “An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question”; he means the national question. The indefinite article (“a Modern Solution”) is misleading. Herzl wrote to Bismarck: “I believe I have found the solution to the Jewish Question. Not a solution, but the solution, the only one” (245). Several times (four to be precise) the text refers to “the National Idea,” which, as Herzl envisages it, would be the ruling principle in the Jewish state and, as I read him, in the rest of the Jewish world too (see Der Judenstaat, 49, 50, 54 and 70). The latter idea, if not explicit, is coiled up inside Herzl’s text. I call his reading of the Jewish Question “the national reading.”

Zionism, both as a movement and as an ideology, has changed a lot since Herzl wrote his foundational pamphlet. It has developed two political wings (left and right); it has both secular and religious varieties; and it has produced a state: the State of Israel. But, fundamentally, Herzl’s take on the Jewish Question—figuring it as a national question, putting “the National Idea” at the heart of Jewish identity—has persisted to the present day. This is reflected in the Nation-State Bill (or Nationality Bill), which, upon being passed in the Knesset in 2018, became a Basic Law: Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish People. The law is “basic,” not only for the constitution of the Jewish state but also for the Zionist goal of reconstituting the Jewish people as “a nation, like all other nations” with a state of its own, as Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence puts it. This means reconstituting Judaism itself.[1]

Why do so many rank and file Jews across the globe appear to accept this reconstitution of their identity? Why did Britain’s current Chief Rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis, call Zionism “one of the axioms of Jewish belief”? How could he write: “Open a Jewish daily prayer book [siddur] used in any part of the world and Zionism will leap out at you.” Zionism, noch, not Zion. When exactly did Judaism convert to the creed of “the National idea”? in January 2009, when Operation Cast Lead was in full swing in Gaza, why was London’s Trafalgar Square awash with Israeli flags held aloft by British Jews? I witnessed this for myself. I was part of a small Jewish counter-demonstration that was spat at and jeered by some of the people—fellow Jews—in the official rally. How did people who are otherwise decent, people who uphold human rights, suddenly become ardent fans of forced evictions, house demolitions, and military violence against unarmed civilians? No doubt, there are zealots who would tick this box in the name of “the Jewish nation-state.” But zealotry is not what moves the mass of Jews to flock to the flag. If they identify with Israel (or defend it at all costs), it is not because they are persuaded intellectually by the “National Idea” (which is what underlies Herzl’s “national reading” of the Jewish Question), but because they feel viscerally the unbearable burden of the Question (which underlies the “antithesis reading”). When they wave the Israeli flag, it is certainly a gesture of defiance, and possibly hostility, aimed at Palestinians; but, at bottom, it is aimed at Europe—not just at the centuries of exclusion and oppression, but at the sheer chutzpah of Europe’s asking “the Jewish Question”—a question to which there is no right answer, because there is no right answer to the wrong question.[2]

But we Jews, understandably, are hungry for an answer that will put an end to the price we have paid for the nature of our difference. Political Zionism might appear to provide the answer. Paradoxically, the Zionist answer consists in taking Jews out of Europe to the Middle East in order to be included in the European dispensation. (Or you could say: normalizing by conforming to the European norm; it’s as if, by leaving, we’ve arrived.) Leading Zionist figures, from Herzl to Nordau to Ben-Gurion to Barak to Netanyahu, have placed “the Jewish state” in Europe, or see it as an extension of Europe. As Herzl wrote, “We should there form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia” (30). More recently Benjamin Netanyahu was quoted saying, “We are a part of the European culture. Europe ends in Israel. East of Israel, there is no more Europe.” So, the concept of the Jewish people becomes ethno-national—just like the real European thing; newcomers, who are largely from Europe, create a home for themselves by dispossessing the people who previously inhabited the land—just like a European colony; they turn their home into a state, just like certain former European colonies (such as the “White” dominions of Canada and Australia). Then there is the way their state—Israel—conducts itself in what is generally regarded as part of the Global South. It subjugates, à la Europe, the previous inhabitants of the land; it systematically discriminates against them; it expands its territory via settlers—a classic European practice; and it enters the Eurovision song contest. In all these respects (except perhaps the song contest), Israel courts a postcolonial critique. The Left are happy to oblige. In a way, the postcolonial critique is the ultimate compliment, the capstone on Zionism’s European solution of Europe’s Jewish Problem.

This prompts a surprising question, one that might seem ludicrous or at least redundant, but follows logically from the argument so far. It is this: Since political Zionism locates the state of Israel in Europe, and since Israel conducts itself in the manner of a European colonizing power, what is so objectionable to the generality of Jews—those who close ranks around Zionism and the state of Israel—about a critique that precisely treats Israel as a European state? The answer is that there is a piece missing from the stock postcolonial discourse, a discourse that folds Zionism completely, without remainder, into the history of European hegemony over the Global South, as if this were the whole story. But it is not; and the piece that is missing is, for most Jews, including quite a few of us who are not part of the Jewish mainstream regarding Zionism and Israel, the centerpiece. Put it this way: For Jews in the shtetls of Eastern Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s (like my grandparents), the burning question was not “How can we extend the reach of Europe?” but “How can we escape it?” That was the Jewish Jewish Question. Like Europe’s Jewish Question, it too was not new; and it was renewed with a vengeance after the walls of Europe closed in during the first half of the last century, culminating in the ultimate crushing experience: genocide. Among the Jewish answers to the Jewish Jewish Question was migration to Palestine. But, by and large, the Jews who moved to Palestine after the Shoah were not so much emigrants as (literally or in effect) refugees. This does not, for a moment, justify the dispossession of the Palestinians, let alone the grievous injustices inflicted upon them by the State of Israel from its creation in 1948 to the present day. But it does put a massive dent into the story told in the postcolonial critique. We need another, more nuanced and inclusive, story.

For Jews in the shtetls of Eastern Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s (like my grandparents), the burning question was not ‘How can we extend the reach of Europe?’ but ‘How can we escape it?’

In a sense, both the “national reading” of the Jewish Question, which Zionism assumes and Israel embodies, and the postcolonial critique of Israel and Zionism, are culpable in the same way: both take an existing European paradigm and apply it to the Jewish case, without so much as a mutatis mutandis. Neither passes muster. Moreover, the omission of what is, for most Jews, the centerpiece of the story behind Zionism and the creation of Israel erases a crucial feature of Jewish historical experience and collective memory. Not only does this erasure vitiate the postcolonial critique, it also feeds the suspicion that many Jews harbor that the critique is malign. It has a familiar ring. They feel, in their guts, that it is another slander against the Jews, a new expression of an old animus—antisemitism by any other name. To put it mildly, this is an exaggeration. The Left, in turn, are skeptical about this reaction. It has a familiar ring. They feel, in their guts, that it is disingenuous, a cynical ploy to suppress criticism of Israel. This too, to put it mildly, is an exaggeration. The more one side reacts to the other side, the more the other side reacts to them. This is not a debate. It is a bout, a wrestling bout, where the two antagonists are locked in a clinch, as inseparable as lovers.

The analysis in this essay suggests that each of the adversaries is in the grip of certain states of mind, connected to particular blind spots. In one case, it is confusion about the meaning of the Question that Europe has persisted in asking about the Jews, plus obliviousness to the injustices done to Palestinians by the Jewish “nation-state.” In the other case, it is confusion over the limits of a postcolonial critique, plus obliviousness to what it is that leads so many Jews to react understandably and, to an extent, legitimately, against that critique. The upshot, on the one side, is demonization of the Left; on the other side, demonization of Zionism. Accordingly, the question each side needs to ask is not “How can I break the hold of the other?,” but “How can I break my hold on the other?” “How,” that is to say, “can I loosen the grip that certain confused ideas and powerful passions have over me?” In short, if a futile bout is to turn into a constructive debate, what is needed is self-critique. This is not asking too much of ourselves. But the task is great, and life is short.

[1] The best treatment that I have seen of a cluster of questions surrounding Jewish identity, Zionism, and the state of Israel is in the work of Yaacov Yadgar, Professor of Israel Studies, University of Oxford. See especially his two books: Sovereign Jews: Israel, Zionism, and Judaism and Israel’s Jewish Identity Crisis: State and Politics in the Middle East.

[2] My current work in this area is focused on developing the idea of unasking the Jewish Question.

A very interesting and thought provoking read. As an Irish leftist I found it illuminating. We too are one of C19TH Europe’s questions. We understand the urge to escape oppression and to have a safe place (our own state). We have supplied a president of Israel, a fact of which many of us are proud. We admire Jewish discourse and intelligence. We are horrified to see Jews become genocidal butchers, as bad as the Europeansthey fled, with just the clothes on their backs. We admire and envy the restoration of Hebrew. So we are conflicted. We admire Jews, we are impressed by the success of Israel but we are ashamed of its crimes. Unlike other Europeans we feel guilt-free in relation to the murder of Jews and we feel morally obliged to call on Israel to behave in line with international law and its own, Jewish morality. Are we holding Israel to higher standards than Syria or Saudi Arabia? Yes. Is it because they should behave as Jews, or as Europeans? Probably.