The historian Marc Dollinger was recently asked to write a new preface for the 2020 scheduled 4th edition of his book Black Power, Jewish Politics. The racial tumult of spring through summer 2020 led to extraordinary sales of the 3rd edition, as was the case for a variety of books addressing racism in the United States. Controversy over Dollinger’s book arose, however, when he submitted his new preface to the publisher. The editors objected to his use of the word “white supremacy” to refer to the attitudes and social investments of certain communities of Jews who welcomed their designation as white in the U.S. racial hierarchy. Dollinger stood by his position, which resulted in the publisher deciding to publish the 4th edition without his preface and to decline publishing future editions of his book. The copyright for any future editions has been returned to him.

A debate on those events quickly followed. The perspective of several critics in the controversy, which amounts to claiming either that no white Jew can be a white supremacist or that any advantages acquired by Jews who are white are earned, not racially bestowed, smacks of overgeneralization and bad faith. They appeal to a form of intrinsic innocence that ultimately defies their humanity.

Professor Dollinger shared the full rejected preface with me in an email exchange. Having read it, my conclusion is that he doesn’t claim that Jewish people in general are white supremacists. He also doesn’t claim that the Jewish people (as a whole) are white. Beyond the preface, doing so in an exchange with me would be weird since he and I have known each other for more than a decade through meetings of Jews of color at the Institute for Jewish Research in San Francisco. What he is claiming is that many European immigrants to the United States were integrated into U.S. society under conditions of assimilation as whites, and many European Jews were not exceptions from that historical, whitening process. Once a white identity was granted, some went so far as to endorse white supremacist views, including eugenics, segregation, social Darwinism, and anti-miscegenation law. Some also blocked anti-racism struggles through fighting against social remedies such as affirmative action and political movements such as Black Power and Decolonization. Among white Jews, this was and continues to be particularly evident among those who embrace neoconservatism, and one could easily find those who identify themselves as white supremacists by consulting the Southern Poverty Law Center. The presence of neoconservative white Jews in a blatantly racist administration such a President Donald Trump’s speaks for itself.

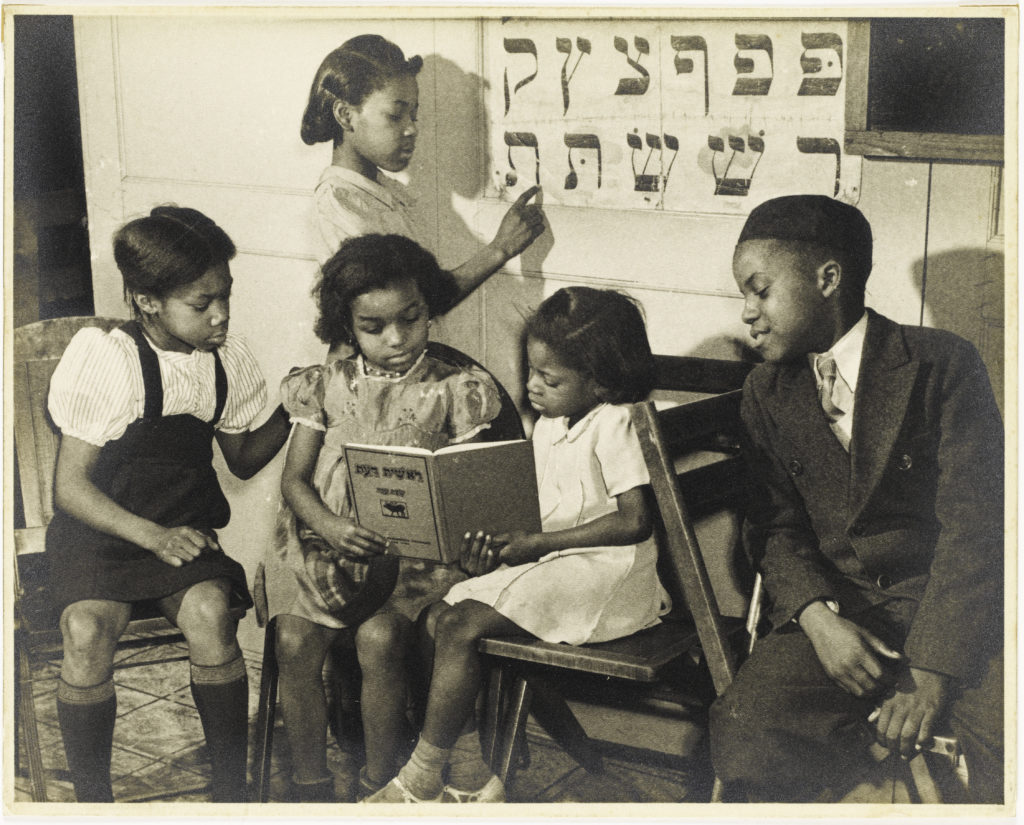

The idea that “real Jew” must be white is a feature of unfortunate misrepresentations of Jewish people primarily during the twentieth century, with steam gathered in its support since the late 1960s.

We should bear in mind that, odd and ironic as this may appear, there are nonwhite people who are also white supremacists, and they, too, often embrace neoconservatism, in addition to forms of populism and fascism. Members of those groups, which include black conservatives who endorse white supremacy through regarding themselves as “exceptions” to a generally pathological black people, gained access to institutions of power ranging from being seated on the U.S. Supreme Court to working in Trump’s Cabinet. This overrepresentation in positions of power makes them appear to be representative of a larger proportion of nonwhite people than what reality reveals. For most Jews on the spectrum from centrism to leftism, the reality is that left-wing Jews hardly have a public voice in the representation of Jews in which neoconservatives have acquired the bully pulpit for at least the past four decades. Many—perhaps most—other Jews never abandoned antiracist struggles. As most black and brown peoples do not embrace bigoted celebrations of white supremacy, their outliers should be understood as just that: outliers.

What makes things difficult for Jews who have become known as “white” is that whiteness was not historically part of Jewish identity. The idea that “real Jew” must be white is a feature of unfortunate misrepresentations of Jewish people primarily during the twentieth century, with steam gathered in its support since the late 1960s.

The bad faith issue at work in the controversy over Dollinger’s ascription of “white supremacy” to white Jews who have demonstrated clear investments in whiteness and have endorsed policies that limit opportunities to nonwhite groups is evident in the claims of those who try to argue accusing them of complicity with white supremacy diminishes what such Jews have “earned. It is a coded version of the “qualifications” and “merits” debate. We should ask: If whiteness is irrelevant to the opportunities many white Jews garnered, why don’t they, then, reject whiteness? If it is their Jewishness that made the difference, how can they explain the socioeconomic and structural differences between the lives of nonwhite Jews and theirs? If they reject their Jewishness as the basis of their achievements and appeal instead to their individual grit, how, then, do they explain the inequalities and negative social-economic indicators of black, brown, and Indigenous peoples in the United States without blaming those people for lacking what it takes to ascend in its clearly white-dominated society?

An unfortunate, underlying trend for “having what it takes” is being designated as white. By this I mean that people designated white have greater options available to them than those designated otherwise. Erased in much of this debate is the long history of “whites only” policies that in effect created a social welfare infrastructure for white supremacy. Yes, there are disadvantaged, individual whites, but white structural power has placed white people as a group at a distinct and historically unjust advantage over others. Although there was discrimination against groups ranging from Greeks to Italians to Irish to European Jews, the fact of the matter is that crucial policies concerning resources were made available to whites and barred from nonwhites.

I regard Dollinger’s point as simply this: acknowledge that there are white Jews who embrace white supremacy. They are not representative of Jews, but they are, whether we like it or not, members of what we call the Jewish people.

This is not to say that these white groups are on a level playing field. There is racial hatred of Jews in the United States, and this hatred has terrible health effects on white Jews on a par with blacks across ethnic and religious lines. There are Jews who would prefer to describe this hatred as a “religious” one, but the fact of the matter is that most people who hate Jews know nothing of Judaism or Jewish religion. And more, racism is more sophisticated than a systematic attitude and the rallying of resources on the basis of mere morphology. There are black people who “appear” whiter than many Ashkenazi white Jews. (I added “white” because there are black, Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islander Ashkenazi Jews.) Among black communities, it is admitted that many—though not all—light-skin blacks have more opportunities available to them than do their darker sisters and brothers. There are light-skin forms of antiblack racism going back to exclusionary African American institutions premised on complexion in the nineteenth century. Similarly, as historians of European Jewish history could attest, there were (and in many places still are) Western Jewish forms of anti-Jewish hatred toward Eastern European and non-European Jews. We would be remiss to make these exemplars of degradation and hate the representatives of each group. But we would also be lying to ourselves if we were to deny their existence.

I regard Dollinger’s point as simply this: acknowledge that there are white Jews who embrace white supremacy. They are not representative of Jews, but they are, whether we like it or not, members of what we call the Jewish people. All peoples have members with values they despise. I take Dollinger to be arguing that even if the majority of Jewish people reject white supremacy, we should identify and put on the table our criticisms of those who embrace it—however deluded or pernicious their reasons for doing so are.

Here are some recent conversations for those interested in podcasts and audiovisual recorded panels on antiblack racism and antisemitism:

Rethinking Black-Jewish Relations featuring Marc Dollinger & Lewis R. Gordon, Adventures in Jewish Studies Podcast, Season 2, episode 7, American Jewish Studies Association (2020).

“AJS 2020 Plenary: Why Racism Should Matter for Jewish Studies Scholars,” December 16, 2020.

“Better Than Nothing Episode 6: Lewis Gordon,” Better Than Nothing, host and interviewer Mark Leuchter (October 2020).

“Jews of Colour: Race and Afro-Jewishness.” Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism. Birkbeck University of London. London, UK. (June 26, 2018).