I write this essay as a Christian social ethicist specializing in transnational feminist ethics. Although I do not produce exclusively confessional or non-descriptive scholarship on religion, interreligious dialogue, or peacebuilding, I still approach religion through a normative frame. As a normative ethicist, I grapple with the complexities of peace activism, framing justice, peace, and love not only as telos but also as guiding moral principles, praxis, embodied knowledge, hope, and imagination for an alternative world.

Atalia Omer’s Decolonizing Religion and Peacebuilding invites readers to critically reflect on their assumptions about interreligious peacebuilding. More specifically, it asks: What if we viewed interreligious dialogue and peacebuilding through the lens of hermeneutical and theological disobedience, incorporating ecofeminist, queer, decolonial, and Indigenous resurgent perspectives? Omer’s fieldwork in Kenya and the Philippines, and the critical conversations she fostered with her interlocutors there, present a compelling case. She argues that many international organizations, religious and non-religious, have co-opted the efforts of local religious actors for their own neoliberal agenda—for example, international development—while maintaining the political and economic hierarchies within those local communities. This often results in the disempowerment of marginalized local actors, whose gendered and raced bodies hold critical knowledge of survival in times of violence and challenge the heteropatriarchal interpretation of sacred texts.

If we, scholars of religion, consider the way that the majority of global armed conflicts concentrated in the postcolonial world are carried out, we would agree with Omer that peace must be decolonized—epistemologically, hermeneutically, and physically. We must ask, then: Where does decolonization happen in religious peacebuilding? It first begins with a critical awareness of the intimate, historical relationship between the Christian religion and European colonialism. Unfortunately, interreligious dialogue often fails to help stakeholders comprehend this dynamic. Omer raises a critical awareness of the “harmony business”—the commodified and depoliticized religious peacebuilding practices often promoted by “religiocrats” in today’s neoliberal world that erase the historical entanglement of European Christianity and colonialism. The book offers vital theoretical and moral checkpoints for scholars and activists, urging us to critically examine whether our work perpetuates a neoliberal or neocolonial status quo rather than advancing a decolonial vision of long-lasting peace with justice in which sexually, racially, and economically marginalized people find liberation.

In the remainder of this post, I raise some questions to further the conversation on decolonizing peacebuilding and interreligious dialogue. These questions are driven by my respect for Omer’s scholarship and activism. I specifically focus on Omer’s distinction between “doing” and “knowing” religion, syncretism, and the ethics of knowledge production. Tying these together is an abiding concern with the way we carry out religious peacebuilding.

“Doing Religion” and “Knowing Religion”

Omer shows that “doing of religion” does not necessarily enhance religious literacy or critical knowledge of religion, particularly if religion becomes a utilitarian tool for peacebuilding. The doing of religion refers to “putting religion to work to promote various objectives” such as the absence of armed conflict in society (3). As a result, the prophetic is turned into what Omer calls the “prophetic lite,” embodied by “an actor who is neither iconoclastic nor disruptive but rather useful and conforming to the NGO-ized deployment of religion as a peacebuilding technology” (3). This globally widespread practice relies on a neoliberal model seeking to include religious people in political peacebuilding by celebrating diversity and eliciting mutual recognition of rituals and spiritual practices. While “doing religion” typically consists of a series of workshops and events in which many religious agents participate, in most cases, the participants do not engage with “difficult questions” that challenge the heteropatriarchal ethno-nation building that is ideologically promoted by their own and other religious traditions. They hardly engage with social justice issues such as gender-based violence, land disputes, child soldiery, marriage, and more from religious perspectives. The danger of “doing religion” is to treat religion and religious people as a monolithic body. Therefore, instead of asking what works in interreligious peacebuilding, Omer accentuates that we must ask “what we can do better” to decolonize and liberate the world for peace with justice. As Omer argues multiple times, decolonizing religion and peacebuilding is “a theological and hermeneutical practice that recovers resources within traditions that are emancipatory rather than oppressive and imperial” (279).

I find it essential to interrogate the relationship between “doing” and “knowing.” Just as “doing religion” does not necessarily enhance “knowing religion,” “knowing religion” as “a discursive tradition or as a living form of historical arguments and interpretations” (4) does not automatically contribute to “doing religion” in the context of peacebuilding. From my disciplinary perspective, “doing religion,” or more precisely “doing theology,” emphasizes that theology is not merely engaging in God-talk but generating actions that will foster much deeper reflection on God. Doing can be a different way of expressing knowing: a religious doer may not articulate the critical knowledge gained through “doing religion” but rely on heteropatriarchal religious symbols and languages to explain their (decolonial) knowledge.

‘Doing theology’ emphasizes that theology is not merely engaging in God-talk but generating actions that will foster much deeper reflection on God.

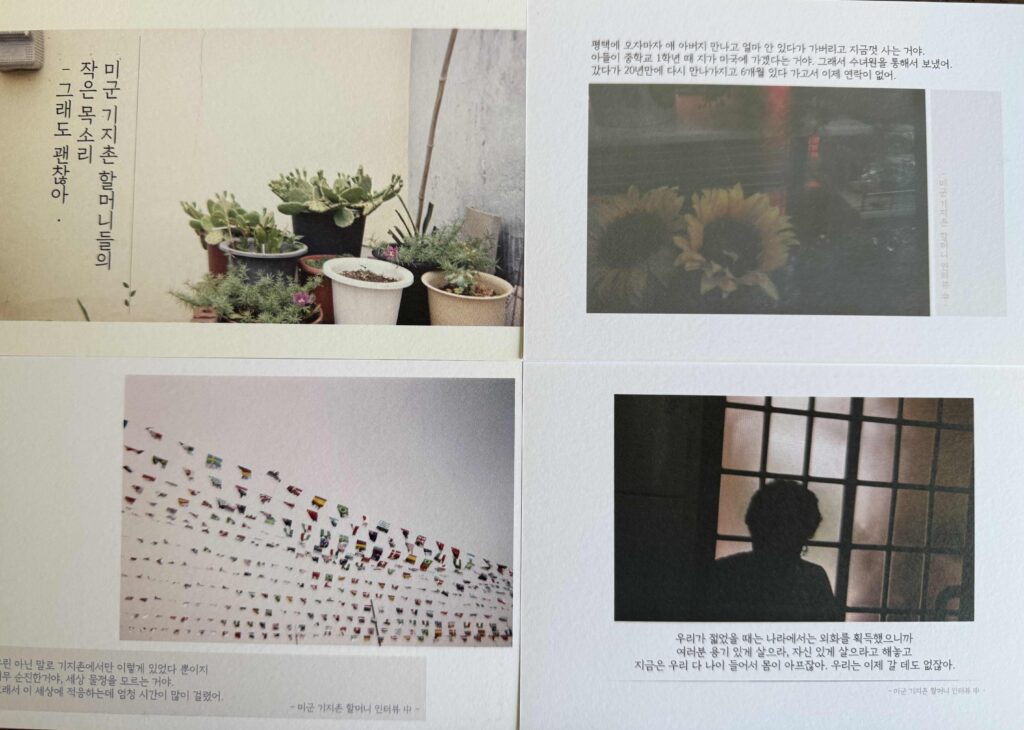

For instance, I find it challenging to decipher ordinary people’s everyday religious languages and experiences while researching women’s peace activism in prostitution industries around U.S. military bases in South Korea. The Sunlit Center, a grassroots organization adjacent to Camp Humphrey’s, the headquarters of the U.S. Armed Forces in South Korea, has advocated human rights for the senior female citizens who used to work in prostitution for American soldiers. The center does not identify it with feminism or Christianity but only with peace activism. However, the organization often utilizes Christian feminist theology or Minjung theology (a Korean version of liberation theology). Every Tuesday, the Sunlit Center women gather for a short prayer meeting or a Bible study, followed by a lecture or critical conversation about the history of and state-sanctioned violence in militarized prostitution industries in South Korea. After educational sessions, they share meals and snacks. One day, I observed the women’s Bible study, where they shared reflections on the New Testament text. When the Bible study leader invited the women to share their interpretations of the text they read, they answered, “O! Thank you, Jesus!,” :I have no idea,” “I don’t know. I’m uneducated,” “Thank you, Father!”

These women’s refusal to share their interpretation of the biblical text reminded me of the conversation between Topsy and Ms. Ophelia in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ms. Ophelia, a “good” Christian woman, asks Topsy, an enslaved Black teenage girl, how she has lived. Giggling, Topsy answers, “I don’t know” to all the questions from Ms. Ophelia. Topsy’s ignorance, childlike innocence, and dirty appearance arouse deep sympathy in Ms. Ophelia, who would later educate and convert Topsy to Christianity (read as White civilization). However, womanist ethicist Emilie Townes interprets Topsy as a strong-willed girl full of survival knowledge who refuses to share her knowledge with White enslavers. Like Topsy in Townes’s interpretation, the Sunlit Center women’s refusal to share their religious and spiritual knowledge can be seen as a form of resistance. Just as Topsy refused to share her knowledge with her White enslavers, these women, through their silence, may be resisting the imposition of a particular interpretation of their faith.

In fact, the older women who used to work in the prostitution industry requested the Sunlit Center to have a Christian prayer meeting because they had fond memories of going to church with their G.I. lovers. They also remembered how the local Korean church ostracized them. The Sunlit Center’s recordings show some of the women’s critical views on Christian teachings of sin related to sexual purity or the prosperity gospel. They exercised hermeneutics of suspicion in an informal and private setting. Although the Sunlit Center women call themselves peace activists unaffiliated with Christianity, they are spiritually empowered enough to go outside to share their stories and protest state-sanctioned violence. Elsewhere, I have discussed their performative bodies as a form of spiritual activism and interfaith dialogue. In the margins of peacebuilding, grassroots women’s inter- and intra-faith dialogue and activism may demonstrate emancipatory, decolonial peacebuilding and religious talk, although their voices are not loud in realpolitik.

Like Topsy in Townes’s interpretation [of Uncle Tom’s Cabin], the Sunlit Center women’s refusal to share their religious and spiritual knowledge can be seen as a form of resistance.

I share Omer’s critique that “doing religion” in the neoliberal and neocolonial space reduces religion to mere functionality, curtailing its profoundly prophetic role in faith-based popular movements. How can “knowing religion” and “doing religion” synergize within interreligious peacebuilding? In other words, how can we hijack “doing religion” from neoliberal political and religious authorities? How can we recognize the intimate connection between knowing and doing? The unity of knowing and doing is the core of spiritual activism illuminated by womanist and feminist scholars such as Layli Maparyan, M. Jacqui Alexander, and Gloria Anzaldúa. In this case, “knowing religion” requires a different form of hermeneutics and an alternative way of thinking about spirituality and religion, as Alexander criticizes heteropatriarchal religion for delimiting people’s imagination of spirituality. Omer’s critical reflection on “doing and knowing religion” underscores hermeneutical competency to decolonize both “doing and knowing religion.” This reflection inspires religious actors in peacebuilding to play “critical caretaking” roles in interpreting religion and building peace.

Marcella Althaus-Reid’s critique of Latin American liberation theology can help us reimagine a decolonial theology. Althaus-Reid criticized Latin American liberation theology for cooperating with a heteropatriarchal neoliberal market economy to attract Euro-American consumers. As a result, Latin American liberation theology depicts the poor as a monolithic group, and thus, a closed hermeneutical body, whose racial, gender, and sexual identities are erased. Their desires are also devalued. The poor in Latin American liberation theology become detached from the realities of the oppressed. Likewise, without critical analysis of the gendered, racialized, and sexualized asymmetry of power among international organizations, nation-states, religious organizations, and stakeholders in peacebuilding, interreligious peacebuilding serves only a heteropatriarchal neocolonialism that keeps the marginalized in their precarious situations for the sake of global peace and security. Omer’s critique of “doing religion” in international peacebuilding elicits Althaus-Reid’s queer feminist theological critique of commodified Latin American liberation theology.

Syncretism

Althaus-Reid’s book, The Queer God, elaborates on decolonial hermeneutics. By queering hermeneutics, Althaus-Reid searches for “God in the closet.” Her notion of libertine hermeneutics is meant to contemplate God metaphorically and symbolically by reading the Bible in conjunction with libertine literature such as that produced by the Marquis de Sade. Libertine hermeneutics reads biblical texts intentionally through a sexual lens in opposition to the Christian colonialist “decent” interpretation of the sexual moral code. To be certain, Christian colonizers used their closed hermeneutics of biblical sexual ethics to subjugate and demonize Indigenous populations who were not subscribed to monogamous heteropatriarchal sexual morality or the binary gender system. Althaus-Reid’s hermeneutics expand to reclaim and renew Indigenous oral traditions, folktales, rituals, and ceremonies. Her queer theology is a syncretic way of doing Christian theology—or, as she claims, a queer theologian is a Christian diaspora.

Without critical analysis of the gendered, racialized, and sexualized asymmetry of power . . . interreligious peacebuilding serves only a heteropatriarchal neocolonialism.

One example of queer theology as a syncretic theology is Althaus-Reid’s theologizing of zemis found among the Taíno people of the Caribbean in the 15th–16th century. Zemis are not gods or goddesses but human-made objects where divine or ancestral spirits reside. Unable to comprehend zemis, Christopher Columbus was only interested in their function. By calling zemis idols, Columbus contradicted his discovery about the natives of the Caribbean islands’ worship of the celestial beings. Althaus-Reid provocatively analogizes thinking about God in postcolonial Latin America to sodomizing God with zemis. In other words, instead of using Christianity to interpret zemis or native traditions, zemis challenged the system of monopoly perpetuated by the God of the empire even in knowledge production and the spiritual market. In order to challenge this monopoly, religious syncretism or a syncretic understanding of hermeneutics can be as much sexual as material, spiritual, and metaphorical.

Is there a place for syncretism in interreligious peacebuilding? As Omer suggests, instead of another source of oppression, religion can be understood as a category complicatedly intersecting with race, gender, class, and other systems of power. Based on this framing of religion, Omer accentuates the importance of critical hermeneutics, particularly developed from feminist, queer, indigenous, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist perspectives, including Althaus-Reid’s. If so, I wonder whether critical hermeneutics, such as feminist and queer theology, and their roles in interreligious dialogue, can be understood and formed better through a syncretic frame? Furthermore, since religious syncretism happens on a more ground level, ordinary people’s everyday survivability can be understood better through the syncretic lens. A critical hermeneutic needs to trace the everydayness of interreligious engagement and dialogue, as well as everyday materiality in religious peacebuilding, namely, embodied peacebuilding.

An Ethic of Knowledge Production

Finally, taking peace activists in Kenya and the Philippines as “interlocutors,” Omer showcases how to produce transnational and intercultural knowledge. As transnational feminist scholars M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty (Chapter 1) argue, transnational knowledge producers should wrestle with the links between the politics of location (e.g., the spatiality of power) and knowledge production; have a sharper focus on the ethics of the cross-cultural production of knowledge; and foreground questions of intersubjectivity, connectivity, collective responsibility, and mutual accountability as fundamental markers of a radical praxis. Alexander and Mohanty’s points of scrutiny constitute a transnational feminist ethics on how we live our lives as scholars, teachers, and organizers, and our relations to labor and practices of consumption in an age of privatization and hegemonic imperial projects. I read Alexander and Mohanty’s ethics of transnational feminism in Omer’s book—especially her conscious practice of relational ethics and friendship—not only as ethics of interreligious dialogue but also as her ethics of field research. I hope this book will inspire many readers to live as scholars, teachers, theologians, and organizers who scrutinize the consumption of decolonization, interreligious dialogue, and peacebuilding in an age of neoliberalism.