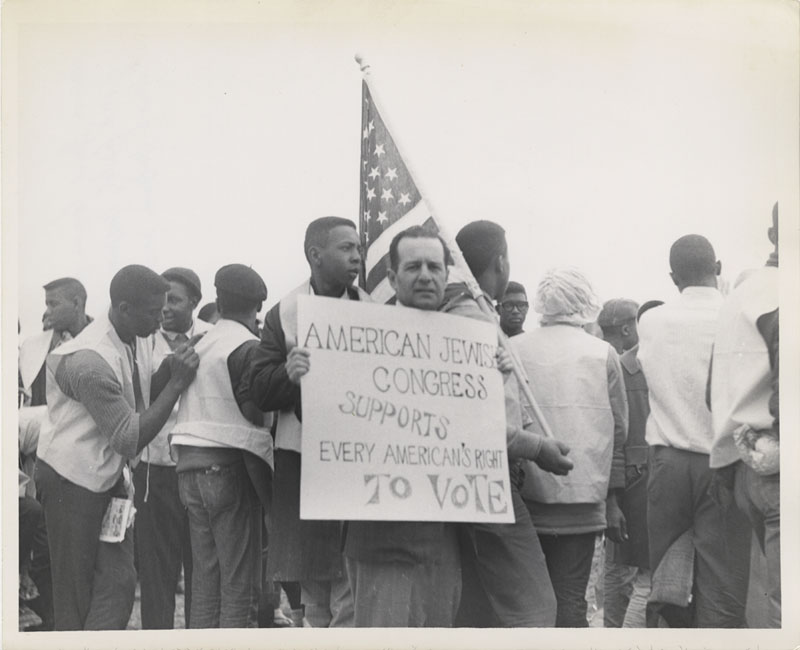

In the Civil Rights era, Jews were disproportionately involved in fighting for the rights of African Americans, or so the story goes. While this is true to a large extent, what is often overlooked is that many Jews, particularly in the south, were far more ambivalent about civil rights than we think. Many southern Jews were quite critical of “northern” Jews coming south to instigate what John Lewis famously called “good trouble,” and then returning home. What bothered many southern Jews was that the presence of Jews from the north would destabilize a very fragile balance Jews had with white southerners. They understandably feared that when the northern Jews went back home, they would be the recipients of white southern wrath. And in many cases, they were right (see P. Allen Krause, “Rabbis and Civil Rights in the South). There were notable exceptions, for example, Rabbi Seymour Atlas whose civil rights sermons in his synagogue in Montgomery, Alabama in the 1950s almost cost him his pulpit. His synagogue board demanded that they vet his sermons before they were delivered.

The complex position of southern Jews during the civil rights movement is an apt frame to revisit the question of Jewish whiteness in these days when renewed race consciousness in Black Lives Matter (BLM) meets an upsurge in antisemitic incidents and the troubling new definition of antisemitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). The latter claims critique of Israel may be included as an antisemitic act. Internal Jewish debate about whether or not to support BLM can be seen as representing a broader unspoken anxiety about Jewish whiteness in a world where critical race theory about both Blackness and whiteness is far more developed than it was in the 1960s.

As Eric Goldstein has shown in his book The Price of Whiteness, in America Jews worked hard to achieve the status of whiteness. Doing so allowed them to climb the economic ladder to success in ways that non-white minorities such as African Americans could not. This is in part the thesis of James Baldwin’s 1967 essay “Blacks are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White,” which argued that it is precisely the social positioning that enabled Jews to succeed in what Baldwin called a “white supremacist” nation that served as at least in part the basis for the animus against them among African Americans. Whether Baldwin’s thesis was correct then, or still holds now, namely that it is largely the “becoming white” of the Jew that African Americans find so distasteful, the success of Jews in America cannot be viewed apart from their “whiteness” in the American Jewish imaginary. When the Tri-Faith America project in the 1930s was underway— this project viewed America as a country of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews—the assumption was that all three religions were white. As Tisa Wenger shows in her book Religious Freedom: The Contested History of an American Ideal, Black Christians were not part of that movement. An important caveat to all this is that there also exists the non-white Jew, a category that often suffers from double exclusion within the American imaginary. This imaginary views Jews as white which, by definition, has no room for Jews of color. The complex status of Jews of color is a topic for another analysis.

Whether Baldwin’s thesis was correct then, or still holds now, namely that it is largely the “becoming white” of the Jew that African Americans find so distasteful, the success of Jews in America cannot be viewed apart from their “whiteness” in the American Jewish imaginary.

What made the Jewish whiteness project so successful in America was that Jews were able to enter whiteness and absorb all its privileges without erasing their Jewishness, thus succeeding as Jews in part because of their whiteness. Aptly labeled successful integration, this also had a darker side as David Schraub shows in his recent essay, “White Jews: An Intersectional Approach.” Schraub makes an incisive argument about the intersectionality of Jewish whiteness and antisemitism. In fact, Schraub argues, the coming together of Jews and whiteness feeds too easily into existing antisemitic tropes rather than diminishing them.

In America, whiteness is largely viewed as a neutral, or unmarked, category. Schraub puts it this way, “Whiteness is a facilitator of social power and status, yet it is typically rendered unmarked. Consequently, the privileges and opportunities afforded to persons racialized as White are often not recognized as such—they are woven into the basic operating assumptions of society, such that their beneficiaries do not even perceive of their existence” (384).

Jews have a different social valence. The classic antisemitism we find, for example, in Houston Stuart Chamberlin’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century first published in 1899, or the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” claim that Jews are dangerous because they are a “superior race.” It is Jews’ power that makes Jews a threat to any society in which they live. Chamberlin claims this is in part due to their low exogamy rates throughout history that have produced a pure race that can easily dominate mixed races. The problem arises when these latent notions are then evoked in response to Jews achieving power in society. Thus modern antisemitism arguably emerges, as David Engel argues, in response to the excesses of power Jews achieved after emancipation in nineteenth-century Germany. Emancipation confirmed what Christians feared about Jews all along. In America, Schraub argues, this results in claims like “I always thought that Jews had all this power and privilege—and see how right I was.” Schraub puts it this way: “The Whiteness frame looks at its subjects and asks that we see their power, their privilege, their enhanced societal standing. So far so good. But stereotypes of Jewishness sound many of the same notes: they look at Jews and point out their putative power, privilege, and domination of social space” (401).

The irony in all this is that Jews in America were able to achieve their power in part because of their whiteness and yet such power is viewed, by whites and non-whites alike, as a result of their Jewishness. George Soros and Sheldon Adelson are two examples from opposite sides of the political spectrum. Soros’s Jewishness is “marked” critically by those on the right, and Adelson’s Jewishness is equally “marked” critically by those of the left. Yet each one attained their wealth in large part because both were beneficiaries of whiteness. Jews, by choosing to retain their Jewishness as they enter whiteness, are not unmarked as “whites” but marked as “Jews” who also have the privilege of whites. And this is arguably what Jews want; they want to take advantage of the opportunities whiteness offers while retaining a sense of difference as Jews. But it may be precisely this dual-identity that is a source of negativity against them. This is not to say that Jews have not been marked simply as Jews and become victims of antisemitic acts. Rather, it is to say that the social tolerance for Jews in America is quite high. In today’s America, a Jew will not likely be shot by a police officer because he is a Jew (although a Jew of color may be shot because h/she is Black). That was not true of Jews in other historical periods, and that is not true today of Blacks in America.

The irony in all this is that Jews in America were able to achieve their power in part because of their whiteness and yet such power is viewed, by whites and non-whites alike, as a result of their Jewishness.

An additional component that speaks to the contemporary situation has to do with the complex relationship of Jewish identity to religion and race/ethnicity. As can be seen through the Tri-Faith American project, Jewishness was defined by religion. For example, Father John Elliot Ross, part of the “Tolerance Trio” that toured America in the 1930s (also including Everett Clinchy and Rabbi Morris Lazaron) as part of the Tri Faith America project made a speech that read, “In all things religious we Protestants, Catholics, and Jews can be as separate as the fingers of a man’s outstretched hand; in all things civic and American we can be as united as a man’s clenched fist” (39). This attitude morphs into the concept of the Judeo-Christian tradition, “Judeo” being a Latinized form of Judaism and not Jews. Jews become part of white America in large part because they are viewed as carrying a tradition that is integral to Christianity.

But as this “Judeo” was being concretized, serving as an entry point for Jews into whiteness, something else was happening to Jews in America: the rise of Zionism. One of the early interventions of Zionism in the American Jewish landscape was to question the religious identification of Jews by arguing that Jewishness was rooted in one’s membership in an ethnic nation or “racial” group. Thus the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, the premier statement of Reform Judaism at the time, expressed that Jews were not a “nation” but a “religious community.” To provide one example within Zionism: Louis Brandeis, one of the early proponents of Zionism in America, made the case in a famous 1915 speech that Zionism and Americanism were compatible because they shared with one another the same values of democracy and humanism. Other American Zionists were highly critical of Brandeis’s unwillingness to shift the focus of Jewish identity from religion (Brandeis was raised in the Reform tradition of “ethnical monotheism”) to nationalism, which was in part a “re-racialization” of Jews. Louis Lipsky (1876-1963), president of the Zionist Organization of America, editor of The American Hebrew and The Maccabean, and later secretary of the Federation of American Zionists, spoke out strongly against Brandeis’s Zionism/Americanism symbiosis. In Lipsky’s words, the old Zionists (referring to Brandeis) refused “to become part of the race and associate themselves with our problems” (71).

The move to re-racialize the Jews, making them primarily an ethnic group as opposed to carriers of a religious tradition, continued through the twentieth century. This complicated the religious dimension of Jewish inclusion in white America (the Judeo of Judeo-Christian), thereby attenuating Jewish whiteness but not erasing it. In fact, in some white Christian circles, Israel actually strengthened the resolve for Jewish inclusion, albeit in a way that also comes with the price of Israel being a part of Christian dispensationalist theology that does not, in the end, affirm Jewish difference but subsumes it into Christianity. For Jews, Zionism is an exercise in political sovereignty. For many Christian supporters of Israel, it makes Jews a part of the Second Coming when they will have one more chance to accept Christ.

In any event, all this reaches our day in a complex way. Jews are still white in America in the sense that they still have access to opportunities open to whites and closed to people of color. Yet Jews are not neutral, and thus not fully white or “unmarked white.” Rather, they carry with them their Jewishness, which has adapted through everything from the Tri Faith Movement to Christian Zionism. Many Jews are also devoted to the fight against anti-Blackness through BLM and to other movements. They have also emerged as critics of Israel’s policies. Yet their participation in BLM and opposition to systemic racism also poses a problem for some within the Black community because Jews participate in them as products of white privilege and all the protections that entails. “Blacks are antisemitic because they are anti-white” may not apply now as it did in 1967, but the whiteness of the Jew has not diminished since that time. How much can Jews as recipients of white privilege truly be a part of a movement against the systemic racism that in part has enabled them to rise to power in white America? Are American Jews willing to forfeit some of that privilege, whatever that might mean, as a gesture to those whose who cannot “pass” into the space of whiteness?

Understandably, Jews want to have both; they want to have the privilege that whiteness offers, and they want to retain the difference that Jewishness requires. Yet it may precisely be this mix that, as Schraub argues, evokes negative reactions against them, both from whites and from Blacks. Their power emerges in part because of their whiteness, yet is invariably “marked” because of their Jewishness. So when Jews support an Israeli regime that is oppressing Palestinians, for many blacks they are simply exercising uber-whiteness as an expression of their Jewishness, showing that they have become so white that they are exporting it as a justification of Jewish power in another country. And when Jews are critical of the Israeli state but still maintain an allegiance to Zionism, some progressives view that as tacit acquiescence to a political structure that systematizes inequality.

Today the fight is not about civil rights, or about equal access to the law. Today the fight is against the white supremacist character of America, it is not about inequality, it is about what Afropessimists call a political-ontology of anti-Blackness. For Jews, as whites, and as Jews, to fully be a part of that fight means to attenuate their whiteness, something we saw was a vexed compromise for southern Jews during civil rights. Jews can certainly fight anti-Blackness as Jews, but that may come at a price; both in terms of their whiteness and in terms of their Jewishness (as many Jews are still aligned with Zionism).

One of the big differences between the Black Power Movement in the 1960s and BLM today is that the former was, as Stokley Carmichael said in his famous Black Power speech in Greenwood, Mississippi in June, 1966 “By Blacks, for Blacks,” while BLM is a multi-racial progressive movement intent on dismantling systemic white supremacy in America. Those who carry whiteness, including Jews, thus have a role in that project. Jews cannot erase their whiteness (they too easily “pass” as white) nor do they want to erase their Jewishness. But Jews can enter this multi-racial movement acknowledging both the benefits of their whiteness and the complexity of their Jewishness that often, although not always, aligns them with a political ideology, Zionism, that today openly engages in racial/ethnic discrimination. Some may disavow Zionism altogether and others may not. But in my view, those who do not must at least recognize the complexity of such an allegiance, and the exceptionalism implied therein, in light of their commitment to fight against the systemic racism on American shores. Jewishness and whiteness in America have always been precarious, and remain so today. Fully acknowledging the knottiness of that equation and closely examining its consequences may be a first step toward more open and honest alliances and partnerships.

A very important and original article. I would like to suggest that while Jews can’t erase their whiteness, we can reject it, actively, in this regard I would ask what the work of Noel Ignatiev and others, also building on Baldwin’s belief that “If you still think you’re white there’s no hope for you,” can contribute to this discussion.