This essay is adapted from the Mirza Family Chair Inaugural Lecture given by Ebrahim Moosa on March 24, 2022. To learn about the gift that established the chair, read more here. A video recording of the lecture is also available as is a recap of the event. A PDF version of this lecture is also available.

Introduction

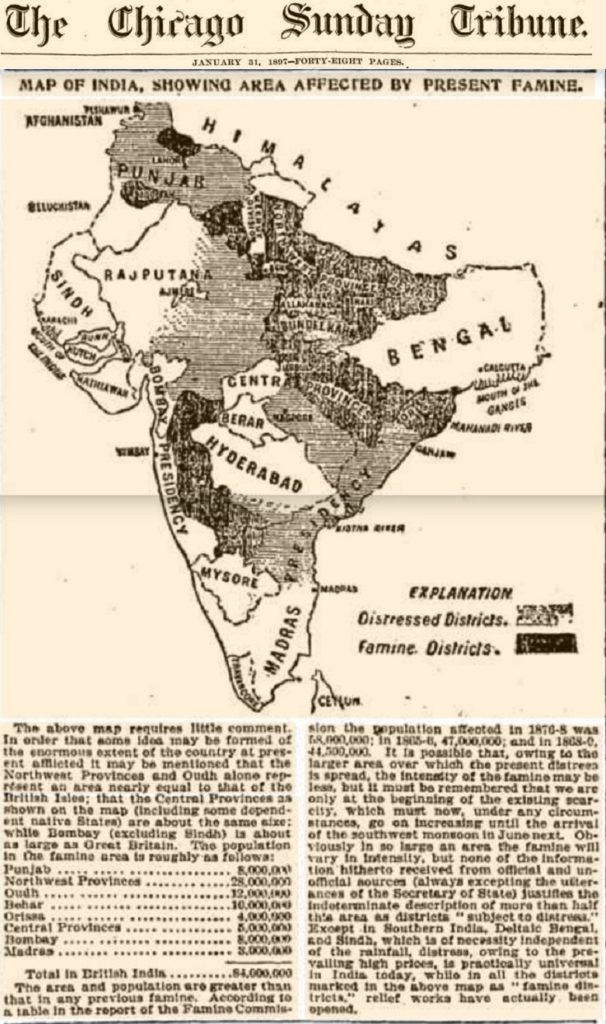

In 1897 a famine affected the Bombay Presidency in India. Also known as the Bombay Province, this administrative territory of British India included some regions south and north of what is today the city of Mumbai. A drought preceded the 1897 famine, which continued into 1899. Famines in British India, the Nobel prize winning economist, Amartya Sen found, were not due to a lack of food (338–54). Instead, inequalities in the distribution of food and the absence of democracy, especially media coverage of the famine, were their main causes. In short, famines had political origins. My ancestors too were refugees affected by a combination of colonial mismanagement and ecological catastrophe long before these terms were invented.

In 1898, at the height of this particular famine, the fourth son of Essa Vally named Moosa was born. His village was known as Vahalu and was located 12.8 kms/8 miles away from the city of Bharuch. Today it is an overcrowded city on the banks of the great Narmada River. As subsistence farmers, my great grandfather’s family was badly affected by the drought. As a result, some started to look for job opportunities outside India, this time made possible by the ability to travel and work in other British colonial holdings. At the turn of the twentieth century, Moosa and his two brothers, Bagus and Adam, followed in the path of several Gujaratis who made their way to southern Africa. When they reached the port city of Durban on the coast of the Indian Ocean, they found the place over traded. They thus travelled further south to Cape Town, which is where they settled around 1902. If we allow for some errors in documentation, one can with some confidence say that Moosa Essa, as he was known, was somewhere between 12 and 16 when he arrived in Africa with his two brothers. Life in the Cape was difficult. There were few people of Gujarati descent, and as such the place felt alienating. His two elder brothers found the rigors of the Cape so unbearable that they hastily returned to India.

Not knowing how to read or write in English, Moosa Essa often used his thumb imprint as his signature on official documents. Our family took his first name as our family name, Moosa. He persevered as a fruit seller, carrying his produce on his shoulders and hawking it to customers in the city of Cape Town. He took up residence in the area known as District Six, which the planners of apartheid destroyed in the 1970s because it defied the policy of racial segregation. Later he opened a store on the famous Grand Parade and by the time he died was known as a fierce businessman, specializing in the banana wholesale trade popularly known as Moosa Cape Town. As a subsistence farmer he knew the value of land. He invested most of his wealth in property both in South Africa and in India. By the time he died, he accumulated a substantial amount of farming land in Vahalu and not an insignificant amount of property in Cape Town.

From famine-ravaged poverty to modest wealth, Moosa Essa never forgot his origins nor his duty to society. He was instrumental, for example, in the building of a mosque in the District Six neighborhood of Cape Town. He also never forgot his origins in his village in India and did not abandon his faith and culture in the very westernizing environment of colonial South Africa under British and later Afrikaner rule.

One could say that my great grandfather was obsessed with his duty to serve his village and community in India and South Africa. No, he loved and reveled in service. This devotion to service stemmed from his faith. He personally supervised every major construction project he undertook. He embodied the truth in the sense that, as Vikram Chandra puts it in his breathtaking novel, Sacred Games, “Love was duty, and duty was love.”

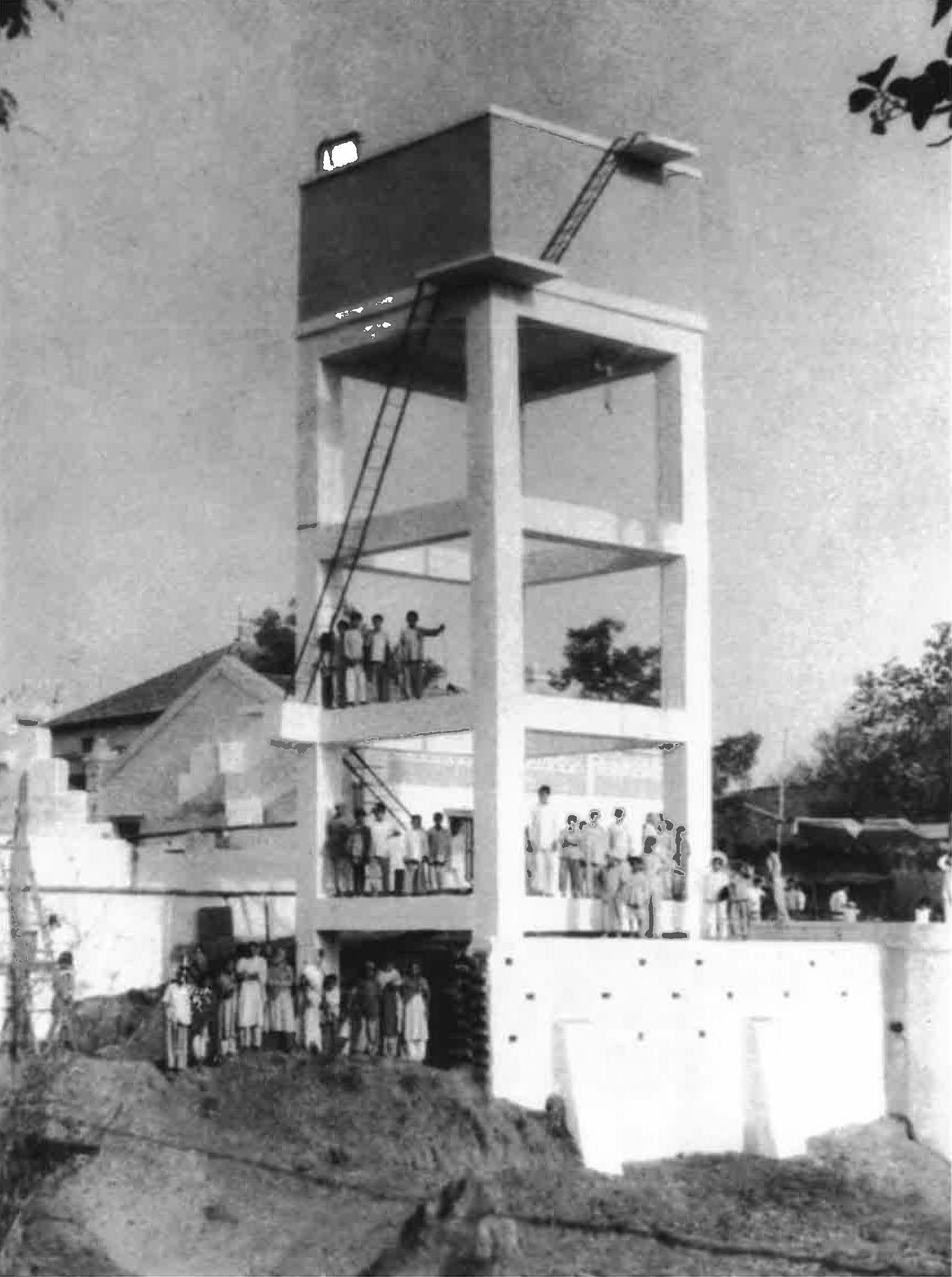

Using his own wealth but also contributions from others, he was the pioneering spirit who oversaw the building of a mosque in Vahalu as well as a grand elementary madrasa, the equivalent of a Sunday School for the daily religious instruction of young girls and boys. He also constructed a water-tower for the storage of well water and built stairs leading into the village pond for the safety of women who used the pond for sundry purposes, including the washing of clothes and utensils. This was long before the village had running water installed in homes. In addition, he built a grand three-level house for himself hoping that his offspring would one day return to enjoy the respite offered by village life and its pastoral environment. No one returned, though I did visit the village during my student years in India. A secular primary school was incomplete at the time of his death on May 15, 1965, but was later completed.

Moosa Essa with groups in village, at the stairs to well, attending a ribbon cutting in the village, the water tower he helped construct, and the school he constructed

In 2005 the entire school building was rebuilt. The doors of the old school that were handpicked and paid for by my great grandfather were preserved and retrofitted into the new school in preservation of his memory. My great grandfather was a man of strong character. He was resilient and kind, but he also had a fierce determination to get his way. A lover of fine horses for his carriage, part of his daily routine in India was to stop and get off his carriage at the shrine of an unnamed saint in the village square, offer a prayer, and then go on to the city of Bharuch to conduct his business. He never stopped trying to improve himself and his community.

The Mirza Chair

I am honored to be the inaugural holder of the endowed Mirza Family Chair in Islamic Thought and Muslim Societies in the Keough School of Global Affairs and with an appointment in the Department of History. One of the key themes of the Keough School is integral human development, an idea drawn from Catholic social teachings. In different iterations, however, this value is espoused by other faith traditions, including Judaism and Islam, but also secular ideologies like Marxism and socialism.

When I study my grandfather’s legacy, I can honestly say that integral human development was baked into his DNA. His philanthropy and altruism centered around service to humanity. His means to these ends were the mosque, faith, and his practical knowledge of the Islamic tradition. He also had a sense of the importance of education as he was not formally educated. Even though he was not literate in matters of faith—he could not read the Qur’ān—and did not read books about religion, he embodied the tenets of his religion in a unique way. He integrated his faith with his society. My wish is for some of these tenets that my great grandfather inculcated in himself to continue to run in our DNA and in our practice as his descendants.

With the inauguration of the Mirza Chair, the irony will not be lost on you that two diasporic legacies come to fruition at the University of Notre Dame, the premier Catholic University in the United States. My family’s history goes back to colonial pre-partition India, then to colonial apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, and now the United States. Muzzafar Mirza, the late husband of Susan Scribner-Mirza, who endowed this chair in memory of him, came from Pakistan to study in the US and then later made this country his home with Sue.

I am relating this story of my ancestors and some parallels to the history of the late Mr. Mirza for two reasons. One is to locate myself in my family’s history, a journey that now connects me to three continents. The other reason is because of the themes which are central to this lecture: history and progress. Many people have the experience of coming from distant lands and locales to this country. Each migration story makes history in one or another way. Does it also represent progress from a worse situation to a better one? What do we mean when we use the language of progress? How does one imagine it and what is its relationship to history? How can we go beyond common sense to grasp these issues? And what does any of this have to do with human flourishing?

The Question of Progress

The idea of progress originates from certain biblical themes of an apocalyptic end along with a mechanistic view of the world wherein its inhabitants aim to create a New Jerusalem. “The idea of progress . . . represents a secularized version of the Christian belief in providence,” wrote Christopher Lasch in his 1991 classic, The True and Only Heaven (40). In numerous apocalyptic writings, according to Ernest Tuveson, history was endowed with a plot and encompassed a narrative of what happened before and what was expected to come. Building on the Hebraic tradition, Christian thinkers and pioneers adapted the Bible’s moral narratives into their own special interpretations of the divine. Saint Augustine, for example, found compelling the idea that history was ultimately progressive, leading to an eschatological end. Later Protestant attitudes also implicitly held that history moves through divinely preordained and revealed stages to a final resolution of human dilemmas.

After centuries of experience, we can now see that there are more deterministic and less deterministic versions of progress. In its strongest posture, progress signifies a particular relation to history: that history has an end (telos) and a predetermined goal. In a more benign way progress could mean advances in knowledge, the betterment of the human condition, and the acquisition of some abilities and the loss of others. In short, on this more benign and less deterministic account, progress might be reframed as improvement.

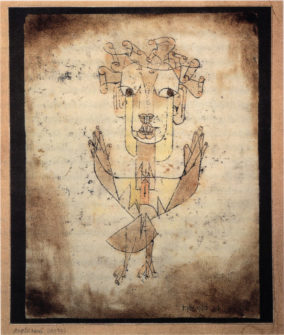

In his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Walter Benjamin meditates on Swiss painter Paul Klee’s (d. 1940) Angelus Novus. This painting of an angel for Benjamin represents the beguiling angel of history. Benjamin’s caution and deep ambivalence towards historicism surfaces in this analysis. Historicism is the theory that social and cultural phenomena are determined by history or that history is the most basic aspect of human existence. In Benjamin’s view, adherents of historicism tend to empathize with the victors in history. They might forget that there are other claimants of history, a lesson Francis Fukuyama ignored in his book, The End of History and the Last Man.

What intrigues Benjamin in the Klee painting is how the angel flies: his wings are spread but his face is turned towards the past. The wings of the angel cannot close because they are kept open by a violent storm from Paradise that propels him into the future. With a strong dose of irony, Benjamin comments: “This storm is what we call progress” (257–58). Even before Benjamin, earlier Romantic thinkers like Herder, Jacobi, Haman, and T. S. Eliot refused to accept the inevitability of progress. In modernity, the possibility of change for the better is a crucial element in how we conceptualize history. This focus on change in history was central to the Enlightenment episteme of ethics and moral philosophy. Modern science as well during this time began to give us a very different understanding of nature than the medieval Aristotelian worldview. The revelations of nature continuously challenged the truths that were taken to be immutable in earlier stages of human history. In late modernity, as I will later explain, we are beginning to question the assumptions of the Enlightenment and its truth because of the ecological challenges we face. Even as the Enlightenment upended certain aspects of the medieval worldview, it maintained its teleological focus on an ultimate “end’ towards which human action tended. In doing so, it recast a Christian worldview that set up humans as having dominion over nature in secular terms. Today the study of history grapples with all the philosophical challenges in late modernity and the Muslim tradition is no exception.

Philosophy of History in Muslim Traditions

What kind of trajectory of time and change does the Muslim tradition offer? To answer this question, I turn first to the period immediately prior to Islam known as the Jahili period. This era was renowned for its poetry, and the Arabs took pride in it as their choicest repository of wisdom. It was a repository in the sense, writes Tarif Khalidi, that it “supplied much of the wisdom and the practical moral standards handed down from one generation to the next.” Proverbial wisdom involved a heroic conception of life where the “unforeseen change from prosperity to wretchedness, the fleeting character of life and friendships, the exhilaration of love and wine, pride in lordly generosity or even-handed revenge” featured in human life (4).

History also often seeks to understand what moral lesson every epoch provides, and thus what improvements might be made as we move into the future.

With the advent of Islam, some of this wisdom was translated into Islamic categories. The Islamic vision of history added a sense of space and time to them. Space and time were ideally inhabited by those who acknowledge God’s lordship and majestic power in creating the world for the use of humans. Human responsibility involved being a witness of God on earth and undertaking the task of stewardship. Time, however, is less of a chronology of events in the Qurʾān and more of a continuum in which past, present, and future are collapsed. Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Muhammad are “eternally present” says Khalidi, and all of history is present to God in terms of divine omniscience. Humans are invited to see the parables in the scriptures and in the handiwork of God in nature. Truth is captured in knowledge and humans are obliged to seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave. By the fifteenth century the writing of history in Islamicate societies had already “transitioned” to new a new conception of history. The earliest phase was a transition from prophetic wisdom to history; from “providential to communal history.” “[F]rom the overwhelming and monumental Qurʾānic time,” writes Khalidi, “to the sequential listing, dating and recording of individual actions performed by members of a community that was beginning to realize the merit of its progress in time . . . and the coming into being of a time scheme which strove to historicize early Islam and to use it to establish hierarchies of moral or social seniority or prestige” (34). History, in my view, can best be described as a series of responses to contingencies and explanations of the conditions in the world. Sometimes these contingencies are expressed in distinctive genres and topics. In some eras, history is preoccupied with the exploits of prophets and kings. At other times, it meticulously documents the lives of influential scholars and pious figures as servants of knowledge and learning. History also often seeks to understand what moral lesson every epoch provides, and thus what improvements might be made as we move into the future.

Two brief illustrations exemplify how history is conceived of in modern Muslim experiences.

In his book, The Road to Mecca, Muhammad Asad documents six years of his travel on camel-back in Arabia after his conversion to Islam in 1926. He talks movingly about his very close friend Zayd with whom he traveled the length and breadth of Arabia. Asad also had a close relationship with King Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia. Zayd however was a member of the Āl Rashīd, a rival kinship group to the Āl Saʿūd clan. In the early years of the 20th century the Āl Rashīd lost out to the Āl Saʿūd in control of the Arabian Peninsula. At one point in the book, Asad and Zayd reach a city called Ḥāʾil. Zayd had not been to the city for many years because the city was now in the control of the Āl Saʿūd.

“How does it feel Zayd, to be back in the town of thy youth after all these years?” Asad asked his companion. Zayd had always refused to enter Ḥāʾil whenever he had the occasion to visit. “I am not sure my uncle,” he replies slowly. “Eleven years since I was here last. Thou knowest my heart would not allow me to come here earlier.” After citing a passage from the Qurʾān about God being the one who gives and takes sovereignty, Zayd adds:

No doubt God gave sovereignty to the House of Ibn Rashīd, but they did not know how to use it rightly…they were reckless in their pride. So God took away their rule and handed it back to Ibn Saʿūd. I think I should not grieve any longer—for is it not written in the Book, ‘Sometimes you love a thing, and it may be worst for you—and sometimes you hate a thing, and it may be the best for you?’ (italics in original)

Muhammad Asad’s comment that follows this exchange is illuminating and wise:

There is a sweet resignation in Zayd’s voice, a resignation implying no more than the acceptance of something that has already happened and cannot therefore be undone. It is this acquiescence of the Muslim spirit to the immutability of the past—the recognition that whatever has happened had to happen in this particular way and could have happened in no other—that is so often mistaken by Westerners for a ‘fatalism’ inherent in an Islamic outlook. But a Muslim’s acquiescence to fate relates to the past and not to the future: it is not a refusal to act, to hope and to improve, but a refusal to consider past reality as anything but an act of God. (159) (emphasis mine)

In this example there is not only a sensibility of history from below, but also an experiential philosophy of life of which history is only a reflection. Important to note is his insight into how Muslims have dealt with the past as an immutable fact. It is a sense of history that leaves the future open, for humans will not achieve except that for which they strive (this is according to a piece of Qurʾānic wisdom). It is that striving that is critical to making history.

If the past is rendered immutable it does not preclude one to act, to hope, or to improve, as Asad put it. Nor is it a future that is preordained, as in the secularized version of progress. In this past century especially we have learned that progress can come at a cost to humans and nature. One thinks of the rain forests in the Amazon that are cut down in the name of economic “progress.” Such actions render the earth more vulnerable to global warming and deprive Indigenous peoples of their homes. Such examples remind us of the importance of Asad’s insight. If the end of history is already set, then there are no contingencies—whether they are ecological or planetary disaster—which might require us to reset or reconfigure our aims.

Fazlur Rahman was a Pakistani émigré scholar to the US and professor of Islamic thought at the University of Chicago who influenced my thinking early on in my career. He expressed his conception of history in the following words: “Islam is the first actual movement known to history, that has taken society seriously and history meaningfully because it perceived that the betterment of this world was not a hopeless task nor just pis aller [a last resort or expedient] but a task in which God and man are involved together” (86).

While history and society feature as crucial elements in Rahman’s writings in the 1960’s, his task at the time was to depict Islam as a civilizational force as well as a faith tradition for individuals. The idea of history nonetheless played an important role in Rahman’s thought. His various studies led him to an understanding of history that allowed one to reshape the normative questions in Islamic thought. For Rahman the story of the advent of Islam, its scripture, norms and symbols, the actual forces of Arabian culture, were all constructively manipulated for a moral cause. “If history is the proper field for Divine activity,” Rahman wrote, “historical forces must, by definition, be employed for the moral end as judiciously as possible” (21). In other words, early Islam revealed the proper end of human action, but it was up to humans to progress towards that end.

Rahman was, of course, a Muslim modernist. He proudly wore that label and thus had a different viewpoint from Asad. Muslim philosophy of history, or more accurately philosophies of history, are somewhat compelled to discern the providential element in history. In the hands of earlier historians, the past was dissected as an act of God. For modernist Muslim thinkers like Rahman, however, there was a greater emphasis on historicism that was similar to that of his earlier counterparts in Egypt, notably Ṭāhā Ḥusayn. On this view, it was necessary to inscribe moral ends as the telos of history. We see here that the secular idea of progress did indeed impact certain trends in Muslim thinking. And on the face of it, few can quibble with these moral ends. The question is: Whose morals are we trying to bring into being? How do you know which morals are the right ones to hold? And should the moral ends necessarily be hitched to the wagon of history? Even when Rahman does rethink his position, he cannot extricate himself from the modern moral circle. “‘Progress’ we all want,” Rahman the philosopher-theologian clarifies, “not despite Islam, nor besides Islam but because of Islam for we all believe that Islam, as it was launched as a movement on earth in the seventh century Arabia, represented pure progress-moral and material” (70).

Here I have hopefully more than telegraphed two modern Muslim modes of thinking with competing accounts of the meaning and end of history. For Asad, the present and the future we create can be an improvement upon the past, but there is no end or guarantee of this. For Rahman, however, history has a moral purpose that ties the past and future together in the march of progress.

Philosophy of History in the West

As already suggested above, the story of history in the west has also shaped the story of history around the globe. The German historian Reinhart Koselleck has explained how the idea of history changed in modernity. For Koselleck this change occurred with a new way of conceptualizing time. Part of this new conceptualization stems from modernity’s prioritization of immanence, in other words the preference for human indwelling in the here and now, over transcendence. For Koselleck, “time is no longer simply the medium in which all histories take place, it gains a historical quality. Consequently, history no longer occurs in, but through time. Time becomes a dynamic and historical force in its own right” (246).

If in the pre-modern world we recounted what happened in the past and called it history, in modernity things have changed. Koselleck says that time is not independent from us, nor does it transcend us, because history is now more about the future and the modern historian is intimately involved in the making of that future. We are time: in our performance of history we embody time. In other words, the individuated self is coterminous with a modern historicism that has now taken center stage in service of “growing united of world history” in pursuit of a collective singular progress (256). A radical insight that requires greater reflection and critique is when Koselleck writes: “History was temporalized in the sense that, thanks to the passing of time, it altered according to the given present, and with growing distance the nature of the past also altered.” (250)

Given the impact of colonization in different parts of the world, history itself acquired a world-historical quality. Because of colonization, it was not unusual that the modern conception of history also affected Muslims around the world. They too wanted to imagine themselves as coterminous with time itself, moving towards an eschaton, be it improvement in the view of some or progress in the eyes of others. During the first half of the twentieth century, many modern educated Muslims emerging from the dark night of colonialism surely wanted to better their lives. To do so, they often willingly adopted certain notions of western and colonial history. In that era to be a progressive or a modern Muslim was a badge of honor; this is no longer the case today in light of the resurgence of both traditionalism and fundamentalism. It is surprising to find that even some thinkers with a traditional background accepted this almost Whig idea of history as progress.

Some Muslim traditionalists thought of every epoch of history as different and an improvement on the past. They argued that this view dated back to a long tradition in Muslim history, which easily fed the modern historical narrative of progress. So, in the view of a fairly broad spectrum of writers, especially those with a predisposition to modernity, one can glean from their writings a sense of a world that can be improved upon. But more generally the accumulation of experiences, technologies, wealth, and resources do make things easier for those who have it compared to those who did not—hence the rich have a duty towards the poor. The idea of progress, in the modern western sense, was embraced by modernists but approached with a sense of ambivalence by Muslim traditionalists. Nevertheless there was indeed a sense of advancing in history and making things easier for people: instead of laboring like a beast, it was better to use a beast and employ tools and implements to make human life more comfortable. There was also a sense that when you use a beast as a means, the treatment should be humane and with integrity; this too was an improvement upon the previous ways animals were treated.

The Ironies of History

Over time, my own work has shifted in dramatic ways. For the story of how I ended up in the madrasas of India for my formative education in Islamic thought I invite you to read my book What is a Madrasa? Post-madrasa life, for me, had several stages. First, I took up journalism in the UK and then South Africa. This was followed by community activism in the Muslim Youth Movement of South Africa as national director—alongside Professor Rashied Omar who was president of the same organization—which combatted apartheid on an Islamic platform. Following this public service, I attended graduate school and began my life in academia.

My extensive studies of tradition, social practices, and the need to develop solutions for faith communities confronting the challenges of modernity often led me to one question: How does a faith tradition—with its myriad practices, beliefs, morals, and ethical ideals—countenance change over time? A faith tradition with seventh-century Arabian imprints that develops and grows into multiple cultures and civilizations must cope with change. Different aspects of a religious tradition, in my view, change according to different rhythms: law and theology has a slower momentum of change compared to economic and political practices. By now you probably have realized that the discursive tradition of Islamic thought has always been a central thread of my practice and intellectual life, as well as to my identity and professional preoccupations.

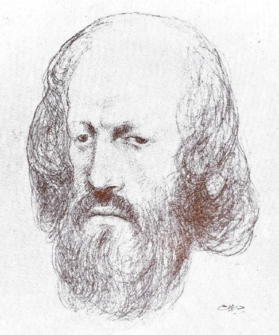

In pursuit of this question of change, I studied the work of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, (d. 1111), a Persian scholar who enjoys an enviable stature in the Muslim tradition. Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas are figures of similar stature in the Christian tradition. Some of my ideas were documented in Ghazālī and the Poetics of Imagination and have bearing on the discussion here concerning history and progress.

In my view, Ghazālī made two major contributions to Islamic theology and philosophy. One was to expand the knowledge framework with which he explained his faith tradition. The second was to allow for spiritual and mystical experiences to also have a place in the epistemic realm. He robustly introduced philosophical and logical arguments in his many theological writings to frame his tradition in the elite idiom of his time, which consisted of philosophical and metaphysical arguments. He was so enamored by philosophy that fellow scholars, both during and after his time, chastised him for grafting Greek and Persianate ideas onto the tapestry of knowledge provided by the Arabian Prophet. He frequently drew on the experiences of mystics to elaborate the inner meanings and subtleties of religious practices. Ghazālī gave equal weight to intuition and discursive reason in a dialectical sense. Ghazālī realized there was a need to ensure religious practices produce ethical outcomes and the “technologies-of-the-self” developed in Islamic mysticism met these goals (see chapter 5). He perceived that there was a need to improve the articulation and practice of Islam that was consonant with a living tradition.

What for Ghazālī might have appeared to be an improvement, development, even progress with a small “p,” was for others the very opposite. And let’s remember that this contestation happened long before the advent of what we call the era of modernity. One such critic was the Kurdish thinker Ibn Ṣalāḥ (d. 1245), a Shāfīʿī traditionalist and an expert in prophetic traditions. Ibn Ṣalāḥ lamented Ghazālī’s claim that whoever did not master logical thinking was not qualified to delve into matters related to legal theory and jurisprudence, a critical discipline in Islamic religious discourses. Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 1201), a Ḥanbalī, was extremely critical when Ghazālī endorsed a controversial sufi practice whereby a spiritual novice who was consciously combatting his pride and arrogance sought out means to be humiliated. One technique was for the novice to go to the bath house and “steal” the clothes of the patrons, and then slowly walk out in order to be detected and thus berated as a “thief” or worse, being beaten. In theory, with such rebuke or beating the novice subdues his ego. In endorsing such a practice, Ibn al-Jawzī proclaimed that Ghazālī disqualified himself from being a jurist, i.e., an expert in legal and ethical topics.

Another critic of Ghazālī was the famous Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Taymīya (d. 1328). Most philosophers, as well as some theologians and mystics, held the fairly standard view that prophecy was a divine gift. Prophecy was not something one could attain based on one’s effort. However, many orthodox authorities nevertheless held that the essence of prophecy was the imagination. Imagination was related to the quality and luminescence of the soul. The gift of the imagination enabled the Prophet and his followers to deal with the contingencies of life guided by the creative imagination burnished by prophecy. Coupled with this view on prophecy, Ghazālī also viewed the development of the soul through spiritual practices to be the culmination of a religious life. Here he welcomed and endorsed many of the practices adopted by Muslim mystics known as sufis.

Ibn Taymīya, by contrast, was clearly opposed to a concept of prophecy that gave an opening to the imagination and certain forms of sufi practices, especially if such spiritual practices had no scriptural mandate. The fear was that these might corrupt Islamic doctrine and practice. In his view, revelation depended on a fideistic, no questions asked, commitment to God. Only such a commitment could demonstrate one’s utter reliance on the teachings of God. This was accompanied by a belief that these teachings were transmitted to prophets via angels. Ghazālī, of course, accepted the traditional doctrine of revelation. But he also made it more expansive to create a significant place for the imagination, since this was, in his view, the highlight of the prophetic event. Ibn Taymīya consistently refuted Ghazālī and later he also targeted the Muslim mystic Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240) with even stronger theological accusations. Ibn Taymīya was unable to come to terms with how revelation affectively works through the power of the soul. To do so would require reexamining the theological guardrails that he insisted such a doctrine must adopt. In Ibn Taymīya’s view, Ghazālī swallowed too much philosophy and this poisonous dose corrupted his thinking and made him divert from strict scripturalist renderings of the faith. Ghazālī, in other words, had betrayed tradition in an attempt at improving it.

For all his fascination with philosophy, Ghazālī nevertheless found fault with the views of the philosophers. He singled out Ibn Sīnā or Avicenna (d. 1037) as someone whose philosophical claims clashed with three theological doctrines. The philosopher, he argued, firstly, denied bodily resurrection and claimed that resurrection on the day of judgment would be in the form of the soul and not the body. Secondly, Avicenna believed that God only partook or knew things that were universal, not particular. And third, the philosopher claimed that the world emanated from God and thus was eternal. On all three issues Ghazālī took a harsh line and declared that such beliefs placed one outside the standard and accepted doctrines of Islam. In my opinion, Ghazālī could have found extenuating circumstances and explanations for the ideas of the philosopher, but he showed no leniency. Later, Averroes, also known as Ibn Rushd (d.1198), in a heroic defense of the philosophers, did a point-by-point rebuttal of Ghazālī’s arguments. He showed that Ghazālī contradicted some of his own canons of interpretation in his theological critique of the philosophers.

Ghazālī thought that he was engaged in improving the discursive tradition of Islamic theological thought through his forays into philosophy, and many welcomed this as an advance on the old ways. In a certain sense this development represented improvement. While his ideas did receive broad reception across the sectarian divide, his approach, as I have shown, was not seen as an improvement by everyone. For some purists his work was a distortion of the original purity of Islam. So already in the eleventh century we can see the contestation over improvement.

History and Tradition

After the collapse of the Ottoman empire in 1922, a range of Muslim thinkers in both Arabic-speaking and non-Arabic speaking regions took stock of their fortunes in order to deal with both their civilizational challenges and the need to engage modernity and the nation-state. One resource these intellectuals and Muslim thinkers turned to was “the heritage or tradition,” called the turāth. The turāth is technically the archive of the Islamic tradition, but the use of the term signifies tradition, broadly speaking. The call to study the tradition stemmed from the fact that the thinkers who made this call were a class of intellectuals who benefited from the West, but were also seeking validation from within Muslim societies. Hence engaging tradition was critical in their efforts to refashion society. In the face of Europe’s rise and of the virtues of enlightenment reason and rationality, Muslim thinkers also wanted to build a civilizational future based on the virtues of rationality. They asked: Why did Muslims miss the boat of enlightenment when Islam and Muslims had a civilization that valued reason and rationality? Did Islamdom not preserve and advance the wisdom of the Greeks and the Indians? How did they lose this wisdom despite the Qur’ān’s constant exhortation to deploy one’s thinking? The answer they landed on was a rather flawed one: they erroneously concluded that Muslim civilization had neglected reason and abandoned rationality for other alternatives such as mysticism. Their fingers often pointed to Ghazālī as the thinker that sparked this turn away from reason.

Those who made this diagnosis claimed that rationalism declined because philosophy was evacuated from Muslim culture. This argument, however, was not substantiated by any sustained and serious historical analysis. Often times, these investigations were animated by nationalisms of different sorts, including Arab nationalism, which was shadow-boxing Iranian and Ottoman claims to preeminence in Islamic thought. Several recent studies have shown that these rather shallow analyses of the tradition as proposed by thinkers like the late Muhammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī and Ḥasan Ḥanafī are palpably wrong, but the myth continues. The myth continues because it makes for an easy scapegoat. The twentieth century diagnostic myth is as follows: rationalism was replaced around the eleventh century by superstition and an extreme reverence for charismatic spiritual authorities, irrespective of whether the latter were dead or alive. Living spiritual authorities created the cult of saints who exercised their power at mausoleums and shrines. This power was exercised on the minds of their unwitting followers with debilitating consequences, the allegation went.

Many today continue to swat at Ghazālī like one beats a piñata at a birthday party. You will also find this narrative that blames Ghazālī for the decline of Islam in popular discourse, such as in public television documentaries like Neil deGrasse Tyson’s reboot of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos.

For a more robust vision of how to grapple with history and tradition than these critics of Ghazālī we can turn to Tunis-born historian ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Ibn Khaldūn (d.1406), who enjoyed a distinct reputation in the past and present for his exacting empirical standards in history but also his philosophy of history. His ideas circulated widely, especially among Ottoman intellectuals and later Western scholars interested in Islam. Among the things a historian needs to know, Ibn Khaldūn impressively lists:

The author of this discipline of historiography needs to possess knowledge of the rules of politics, the true nature of existing things, the differences between different commonwealths of people, locations, periods with respect to ways of living, character traits, customs, sects, schools of learning and all relevant and associated conditions. And how the present is comprised by these elements. The historian must be able to gauge the similarities between the present and the past and the distance between the present and past in terms of their differences. And the historian must be able to analyze the causes of the similarities and the causes of the differences. So too must the historian grasp the foundations on which political dynasties and religions were established; the causes that made them become manifest; the reasons they came into existence and the incentives for their being as well as the conditions of those who established these dynasties and religions and their respective histories. This is necessary for the historian to fully grasp the material cause of every event and the rational principle behind every account. Then only can the historian evaluate transmitted reports based on what he possesses of rules and rational principles. If the narrative complies with the rules and principles and meet their criteria it is deemed sound; otherwise, the historian deems it spurious and dispenses with it. (1:55–56)

Ibn Khaldūn also laments the fact that much historiography fails to account for the changes that occur among a collectivity of people. When one political dynasty dies and another is given birth to, various customs and political practices will undergo change. Additionally, after several decades of rule practices might look very different from how they did at the beginning.

A historian must not project her or his own subjective experiences onto the past when examining it, he warned. But this is also a warning against presentism: reading history in terms of our own experiences. Ibn Khaldūn admits that it is natural for humans to see similarities and analogies at first blush. But often this is a recipe for error. Someone even well-versed in history can sometimes be oblivious to the changes that societies have undergone. Unhesitatingly the person projects the knowledge of the present onto the past and then measures the past based on one’s own experiences. This is a capital error on Ibn Khaldūn’s understanding. Many modern historians of Islam project the experiences of the present to bizarre causes in the past.

At the beginning of Islam and through the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties, Ibn Khaldūn asserts, knowledge was not a craft or discipline. Knowledge was equal to a handed-down body of teachings, a tradition that enjoyed a different status. Knowledge was what one had heard from the Lawgiver, meaning from the authority of the Prophet and what he taught of the Qurʾān. The main function of knowledge of the faith was to guide people in specific ways of living.

More importantly, knowledge of the tradition in this early period was shouldered by persons of prestige, dignity, and influence who wielded the power of persuasion (aṣabiyya), like the Umayyad governor Ḥajjāj b. Yūsuf al-Thaqafī (d. 714), who hailed from a family of influential teachers. In other words, the knowledge actors were also in a sense the political leaders. Hence, the knowledge of faith was baked into the political system of early Islam. Today we will say that the faith tradition was mirrored in the political theology of the early community and vice-versa. If worldly success and ethical living are the requirements for afterworldly success, as the Qur’ān taught, then it was not inconceivable that there should be a relationship between the order of the political and that of the spiritual realm. The Prophet appointed his most senior Companions to the task of transmitting knowledge because it was critical to the identity of the community, reported Ibn Khaldūn. His crucial point is this: in this early stage the transmission of knowledge of the faith was closely associated with people of prestige, influence, and those who had ties of solidarity with the political dynasty that Islam established. It was in the form of a tradition, naql, that they grasped what Islam meant.

Several generations later the character of the knowledge of the faith tradition changed. Ibn Khaldūn is a bit vague on when this exactly happens. But based on his experiences in Mamluk Egypt in the fourteenth century, he was confident that knowledge of the tradition was no longer part of a founding political narrative during his time. The political tradition became somewhat quasi-independent, with profound consequences for the knowledge tradition that regulated theology, law, and philosophical ethics. Muslims had by his time, seven centuries later after the founding of Islam, developed an entire corpus of laws dependent on the early tradition. The corpus of knowledge also advanced different understandings of these laws compared to the early tradition. So, examining Islam as a fully-fledged discursive tradition, as Talal Asad describes it, requires a complex sensibility of the various mutations of tradition, especially the role of politics in the making and practice of tradition. Multiple understandings of tradition were made more complex by debates centered on knowledge of the tradition, a perspective seriously ignored in earnest contemporary studies of tradition.

As part of a unique Muslim Republic of Letters across multiple geographical regions, this discursive tradition not only expanded in terms of substance but also in terms of space. It consisted of contributions from Muslims in Persia, Central Asia, India, North Africa as well as the regions of Western Sudan and the Iberian Peninsula. This vast emerging corpus of scholarship gradually became canonized via an extensive and dizzying array of disciplines, each with protocols and rules of interpretation. In other words, diversity was a major hallmark of Muslim knowledge traditions. Gradually organized scholarship became part of a habitus, an organized way of living. But this organized way of living around a knowledge tradition was now arranged differently and conceived of differently compared to how it was imagined at the very inception of Islam.

Given the needs to educate the emerging communities of early Islam, scholarship became separated from the centers of political power and was independent from the individuals who now led the political enterprise, according to Ibn Khaldūn. He observed that in the later period those who conducted royal and political affairs were too arrogant and preoccupied with their governmental authority to devote attention to education related to the faith tradition. Hence, less powerful people now took up the mantle of education. Some of them were descendants of former slaves and others came from humble backgrounds. As a result of the esteem conferred upon them as carriers of the knowledge tradition of Islam, their status was elevated, but their status was different compared to the political classes.

Ibn Khaldūn’s somewhat jaundiced view of the disinterest of the political elites in knowledge of the faith tradition might be clouded by his personal experiences. Nonetheless, the critical insight Ibn Khaldūn offers is a persuasive account of how knowledge of the tradition also changes with a change in time, place, and political context. It augurs improvement as well as difference.

This insight ought to be helpful to contemporary Muslims and their thought leaders, for it is precisely in the domain of knowledge and how to construe knowledge of tradition in which there is a great deal of hesitation for promoting change today. But what remains unsolved and a dilemma for scholarship to this day is this: If the founding template of knowledge was very much hewed to the order of obedience to God and tied to the order of the political then how can one unscramble the teachings of obedience to God, dīn, from political obedience? Is the political order merely the domain where practical questions are taken up? In the past, the rise of Sufism created some distance between the concerns of the soul and the realm of the political by insisting that faithful living should avoid the realm of the political as much as possible. And in the modern period this historical template is still very much the arena in which Muslims are experimenting with different kinds of approaches to unscrambling or reassembling the architecture of religious thought, especially in relation to the rise of the secular and secular politics. Debates in this sphere involving political and intellectual discussions goes under the moniker of Islamic reform. The question we can now turn to is: What constitutes progress in this schema?

The Ambivalence of Progress: Progressive or Critical Traditionalism?

Muslims in modernity are not immune to the dominant view of progress. In other words, the secularizing influences in the Islamic world are real. What distinguishes a dyed-in-the wool modernist from someone who is less enamored by everything modern is that the modernist believes in the inevitability of progress. However, the opposing view, say the critical traditionalist perspective that I have been advocating, sometimes grudgingly concedes to the possibility of change or improvement. Improvement as fortuitous, rather than as inevitable, holds the promise that change might occur in diverse and multiple forms. This stands in contrast to the totalitarian narrative of progress driven by scientism and liberal capitalism. The deterministic or apocalyptic theory of progress locks everyone in a suffocating straitjacket of a singular modernity. Ignoring this subtlety can produce some of the most irreconcilable dilemmas and forces one to choose between science and religion, rationality and faith, and progress and tradition.

In my work with recent graduates of the madrasas of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh in the Madrasa Discourses program which operates within the Contending Modernities project at the University of Notre Dame, we confront endless dilemmas about how to deal with a plethora of knowledge traditions, the histories and geographic locations of dominant knowledge traditions, and the multiplicity of human ecologies they serve. The invitation to help prepare the next generation of madrasa graduates to meaningfully deal with their lived realities came from the leadership of a section of the madrasa community. Mawlana Amin Usmani, the secretary general of the Islamic Fiqh Academy of India, repeatedly implored me to help him train the next generation through a stream of letters and emails. This invitation was acted upon when I moved to Notre Dame and started the program with the generous funding of the John Templeton Foundation.

In the same way as I once learned to encounter the challenges of modernity, many of the participants in our program also wanted to engage modernity while still retaining their Islamic tradition. Here it is a question of negotiating multiple literacies while being aware that modern literacy can be both enchanting and alienating when it is brought to bear on a historical tradition.

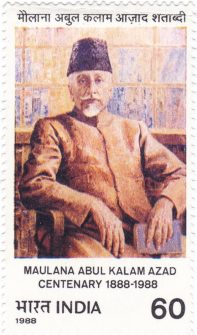

This kind of grappling with tradition in the face of modernity is not new, though it is perhaps underexplored in the scholarly literature. An exemplar who wrestled with tradition is Abul Kalām Āzād (d. 1958), the famous anticolonial activist and political figure who served in the post-independence Indian government as minister of education. Āzād is well known for his significant political role as a leader of the Indian National Congress alongside the peace activist and freedom fighter Mahatma Gandhi and independent India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. However, there is another dimension of his formation that has received less attention. He was also a virtuoso traditional Muslim scholar, whose education was meticulously crafted in his father’s madrasa. Few have paid attention to his subtle and insightful understanding of tradition against a backdrop of doubt and anxiety produced by the rigors of modernity.

In dealing with his own Islamic tradition there is something poignant, if not tragic, that haunts Āzād. As an innovator of ideas, Āzād sought to remake his state of mind, in short, his psychology. We can follow Nietzsche’s wisdom on this matter. Nietzsche urged one to turn against oneself and arouse fear of oneself, in one’s quest “to overcome the gods and the tradition in themselves” (115). Āzād was fully aware of the burden and risk of turning against oneself and one’s tradition.

At some point as a young adult, he sought out a teacher in the fringe neighborhoods of Calcutta to teach him to play a musical instrument. This was a scandalous desire for a Muslim theologian who was destined to become his father’s spiritual successor. Why? Listening to music was already controversial and viewed as unlawful in the eyes of some who identify as orthodox guardians of the Islamic faith. Āzād knew that in such an environment becoming a musician was suicidal and reckless. But his transgressive search to play a musical instrument was part of a wider questioning attitude that overtook Āzād. This episode of self-questioning is not uncommon to people who study at a madrasa, yeshiva, or seminary. Āzād wrote that at the age of fifteen the certainties provided by tradition began to disintegrate and “the peace of my mind began to tremble, and the thorns of doubt and skepticism pierced the heart.” He continues: “In addition to the voices I heard from all sides, I also felt that something else was lacking. I felt that the universe of knowledge and reality is not limited to what was in front of me. As I advanced in age these pricks of conscience continued to grow” (99–100).

Assailed by doubts, all his beliefs disintegrated and he himself pushed over the remaining ramparts of his convictions. He then set out to find new fortifications.

Āzād not only found rhetorical support in literature, but also deployed literary resources to reach into the depths of the human condition. Dwelling on his conditions of doubt and the remaking of the constitution of his mind, he found solace in the poetry of the Persian émigré poet to India, Kalīm Kāshānī (d. 1651), who was buried in Kashmir.

Kāshānī wrote: “My desire to know has never ever thwarted me/Even on the day of the richest harvest, I still do go out in search of sustenance” (100). In one passage from his famous memoir and literary masterpiece titled Accumulated Dust, which consisted of letters written from jail, Āzād very honestly grapples with the multiple worlds he has to negotiate:

One’s traditional convictions are the biggest obstacles in the path of one’s mental development. No power can incarcerate a person as much as the chains of traditional convictions can fetter one. One is unable to break these chains easily because one does not really wish to do so. In fact, one prizes these fetters of tradition like precious ornaments. Each doctrine, practice and viewpoint gained through one’s family heritage and by means of one’s foundational education, accompaniment, and apprenticeship (sohbat) will be cherished as a sacred inheritance. One will defend this heritage at all costs. But one will never have the courage to meddle with it. Sometimes the grasp of inherited convictions is so strong that even the most effective education as well as environmental changes cannot unshackle its hold. Education will to some extent influence the mind, but it cannot influence the constitution of the mind. One’s mental edifice is always constituted by a line of descent, by family and by centuries of successively transmitted traditions, and whose hand will always effectively do the work of tradition. (100)

Here Āzād exemplifies the dilemmas produced when one must negotiate very different legacies of knowledge at a time when the space for difference and multiplicity is radically shrinking. His words speak to us today as much as they did to those during his time.

History and Tradition in the dihlīz (interstice)

What I have learned from my studies and experiences has made me more tentative in pronouncing muscular solutions to complex problems. What I learned from Ghazālī was the immense value of the in-between space (dihlīz) of daily living and reflection. The spatial metaphor of a threshold or portal, a dihlīiz—an intermediate portal separating the Persian home from its exterior—represents a productive dialogical space. From Ghazālī and countless others we learn how intellectual productivity was enhanced at the interstices of cultures. Ghazālī imagined and theorized all thought and practices to be a continuous dialogical movement between the inner and the outer; the esoteric and exoteric; body and spirit in a productive fashion. He did not configure the dialogic in a simplistic binary relation, but he imagined these to be the multiple nodes in a force field.

Suspended within this force field was the subject diligently tending to the needs of both matter and spirit. Underlying all our critical activity is a complex hybridity and fuzziness, despite our every pretension to smooth it out. And while over the longer duration we can sometimes observe dramatic shifts in knowledge, on most occasions we pass through transitions, creases, and folds in knowledge and time. Improvement is possible, in other words, but progress is halting.

The perpetual quest is to seek emergent knowledge arising out of our struggles and transitions for alternative futures. We do know one thing taught by experience: the dominant paradigms need to be continuously contested with alternative ways of knowing, different types of knowledge, and novel models for society-building. The future, as Boaventura de Sousa Santos pointed out, has become a personal question for us, a question of life and death. Or, as Amitav Ghosh tells us in The Nutmeg’s Curse, something more fundamental needs to be addressed: we have to revise our understanding of matter and the vitality of natural and celestial objects. As he put it, “The hold of the economy on the modern imagination has progressed to the point that capitalism has come to be seen as the prime mover of modern history, while geopolitics and empire are regarded as its secondary effects” (116).

We do know one thing taught by experience: the dominant paradigms need to be continuously contested with alternative ways of knowing, different types of knowledge, and novel models for society-building.

In order to pursue better and improved futures we also need the past, we require the insights of history. We need history to help us imagine, not ready-made solutions, but creative problems to be addressed. “Certainly we need history,” Nietzsche wrote. “But our need for history is quite different from that of the spoiled idler in the garden of knowledge,” he continued, adding: “…[W]e require history for life and action, not for the smug avoiding of life and action, or even to whitewash a selfish life and cowardly, bad acts” (7).

Many of the thinkers I have discussed were in one or another way compelled to reread the past and now view it as an immutable act of God empowering us to hope and act in search of an open future. Unfortunately, too many thinkers have understood the betterment of civilization in stoutly economic terms, linking the division of labor to the development of society. It may well be part of the truth, but certainly it is not the whole of the truth. For it is practice, as secular moralists would describe it, or the prophetic activity as religious actors would articulate it, that allows us to dedicate ourselves to life. A life premised on balance and distribution is one that avoids a nihilistic end. The improvements we make in giving shape to that prophetic spirit—a life of practice and the will to power—opens the possibilities for new histories, not the inevitability of history and certainly not the end of history. For those, like Ahmet Karamustafa, who view history as a continuous struggle, a gift carrying the possibilities of improvement, the cultivation of civilization remains inviting and utterly tempting.

In conclusion, I want to share from the writings of the littérateur, proponent of mysticism and philosopher, Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī (d.1023). Tawḥīdī was the protégé, if not the “Boswell,” meaning an amanuensis, of Abū Sulaymān al-Manṭiqī al-Sijistānī (d.c.985), his mentor. It captures the messiness of the human condition and especially our earnest efforts to understand complex realities and mysteries. The citation comes from Tawḥīdī’s meditations on coincidences and oddities. But the terms coincidence (ittifāq) and the unexpected (falatāt) do not do justice to the meditation. I think what he intends to say is that things like history, progress, and improvement are complex, imbricated, meshed and messy, yet also distinguishable, and appear to us as the unexpected. Tawḥīdī attributes the fulsome nugget of wisdom to Abū Sulaymān who says:

Things are distributed according to the limitations of nature, psychical powers, intellectually indivisible elements, and divine wonder. What exists here on earth is therefore necessarily either something familiar that is related to nature, or something rare related to the soul, or something unique that is related to the intellect, or something wonderful that is related to the divine being. The unexpected is among the last-mentioned kind; I mean it permeates these various classifications.[2]

History is about contingency. The unexpected is perhaps the most fertile ground of history and where the possibility of improvement, rather than progress, exists. What Tawhidi’s insight reminds us of is that the unexpected is enmeshed in our understanding of nature, our psychology, and divine wonder. Nature, the person, the human mind, and the role of the divine cannot be separated in our understanding of history. If we ignore them, we do so at our own peril. But more so, the result is an impoverished understanding and appreciation of history and the discontents it brings.

*The author wishes to thank Joshua Lupo for his editorial assistance in preparing this post.

[1] Ibid.

[2]Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī, Kitāb Al-Imtāʿ waʾl-Muʾānasa, ed. Aḥmad Amīn and Aḥmad al-Zayn, 2 vols. (Beirut: Manshūrāt Dār Maktabat al-Ḥayāt, c. 1960), 2:160; With emendations the translation is from Geert Jan van Gelder, “On Coincidence: The Twenty-Seventh and Twenty-Eight Nights of Al-Tawḥīdī’s Al-Imtāʿ wa-l-Muʾānasa. An Annotated Translation,” in Medieval Arabic Thought: Essays in Honour of Fritz Zimmermann, ed. Rotraud E. Hansberger, et al. (London; Turin: Warburg Institute; Nino Aragno Editore, 2012), 216.