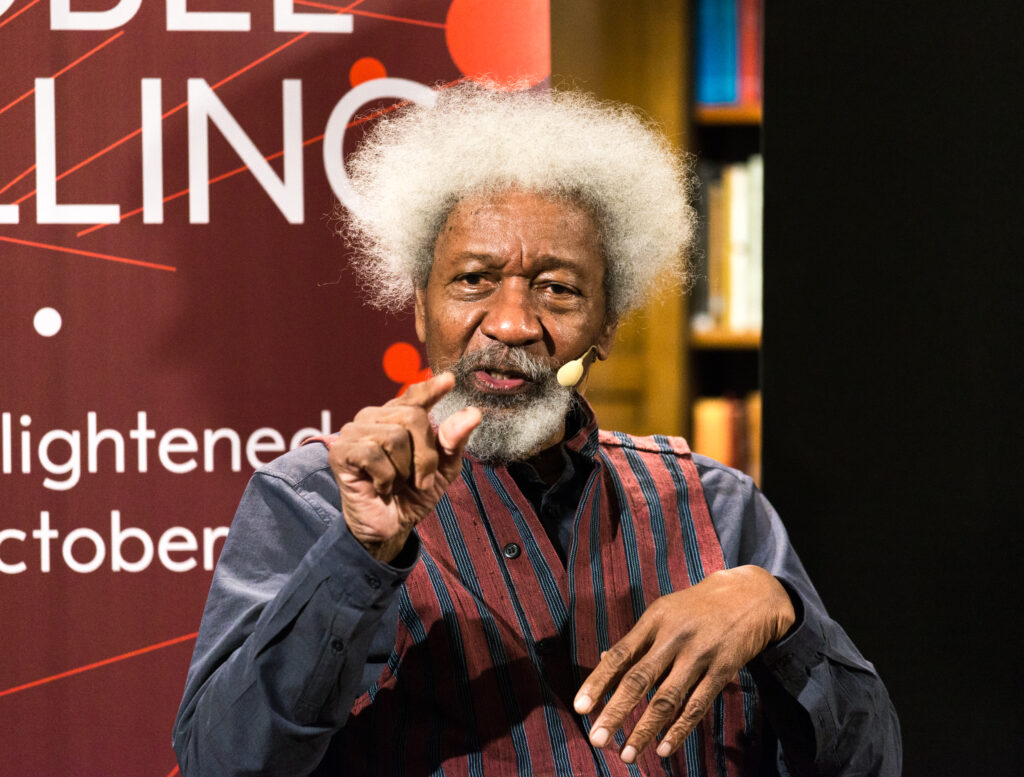

The Nigerian writer and public intellectual Wole Soyinka, in his book-length essay Of Africa, refers to new religious movements in Christianity and Islam, including Pentecostalism, when writing that “religion, alas, on the African continent, has moved in recent times beyond the luxury or mere abstraction or academic exercise. It has leapt to the forefront of global concern … [and] it threatens the very fabric of a continent that, only a decade or so ago, considered herself immune from the lunacy of faiths” (131). One can safely assume that Soyinka, who is widely known for his “radical agnosticism” and religious skepticism (see Celucien Joseph’s recent book about Soyinka on religion), would consider the Pentecostal pastor, and the cult around him, as a primary embodiment of the religious fanaticism he is so concerned about. One can also safely assume that Soyinka would sympathize and probably agree with the critical analysis of this phenomenon offered by Ebenezer Obadare in Pastoral Power, Clerical State.

Soyinka himself is mentioned in Obadare’s book as a prominent member of the social class described as “Men of Letters,” which according to Obadare is of “yesterday” because the public status, authority, and influence this intellectual elite once enjoyed in postcolonial Nigeria has been taken over by, indeed, Pentecostal pastors as self-proclaimed “Men of God” (26–27). Although there is a significant element of truth in this account of a passage of authority of ‘“yesterday’s ‘Man of Letters’ to today’s ‘Man of God”’ (4), in the present contribution to the symposium about Pastoral Power, Clerical State I want to complicate this narrative and ask whether Obadare might be writing off the Men of Letters too early. In doing so, I want to foreground the ongoing relevance and significance of literary writing as a site of creative critique and reimagination of Christianity, in particular Pentecostalism. A preliminary note is that although I can’t fully avoid using Obadare’s androcentric language, it’s important to acknowledge that women are an important part of the constituency of Pentecostal pastors as well as of literary writers.

The “Man of God” as a “Man of Letters”

One complication of Obadare’s framing is that contemporary Pentecostal pastors appear to be rather eager to embody the personae of a “(Wo)man of letters” themselves. As much as Obadare mentions university professors in Nigeria who adopt the title “pastor” in order to regain some of their lost social status, the reverse is also true: many a pastor proudly carries the academic title of Doctor or Professor (honorary or not) in combination with their religious title, indicating that at least the pretension of academic credential and intellectual caliber is vital to their performance as religious, social, and political entrepreneurs. Moreover, pastors frequently cast themselves as Men of Letters in a literal sense, as they boost their public profile with a prolific output of books, usually published by their church-linked publishing houses. To cite only one example, David Oyedepo, the founding pastor and presiding bishop of Living Faith Church International (also known as Winners Chapel), prides himself on having “published over 90 impactful titles most of which have been translated to major languages of the world such as French, Chinese, Spanish etc. with over twenty million copies in circulation.” Most if not all of these titles were published through his own publishing house, Dominion, the mission of which states that “knowledge, which is a product of learning, is a key factor in the liberation of man.” Whatever one thinks of the quality of the writings by Oyedepo and the likes (and I admit to having some reservations about this), one could well argue that Pentecostal pastors have been more successful in promoting a reading culture in Nigeria (and beyond) than the whole class of intellectual Men of Letters before them. The phenomenon of (Wo)men of God casting themselves as (Wo)men of letters raises questions about the boundaries between these two categories, which obviously are blurred unless one adopts an elitist view of what the real (Wo)men of letters are about.

The Continued Relevance of “Men of Letters”

However, my focus in this contribution to the symposium about Obadare’s book is a different one. Drawing attention to the ways in which Pentecostal pastors have recently been featured in contemporary Nigerian literary texts, I complicate the suggestion that the Men of Letters belong to the past. Instead, I want to highlight their ongoing role in the public critique of Pentecostalism, in particular the figure of the pastor. For the purpose of this discussion, I understand Men of Letters here as referring to literary writers (male or female) who, as Wale Adebanwi has argued, play a vital role as “social thinkers” about contemporary African realities. Obadare, in the introduction to his book, makes brief mention of the writer in their role as social thinkers in relation to Pentecostalism when he quotes the novelist Elnathan John who, in his satirical book Be(com)ing Nigerian: A Guide, observes that “Being a pastor is one of the most rewarding things you can do as a Nigerian.” Needless to say, the rewards of be(com)ing a pastor are well-spelled out in Pastoral Power, Clerical State.

John has offered a more expanded satirical critique of the figure of the Pentecostal pastor in his graphic novel On Ajayi Crowther Street (illustrated by Àlàbá Ònájìn). Published by the Abuja-based press Cassava Republic, this novel has been described as a “gossipy, Lagos-set morality tale.” It centers around the lives of Pastor Akpoborie and his family, with the pastor being unfavorably depicted as a moral hypocrite and religious charlatan. In the novel, Akpoborie harasses and rapes the housemaid while subjecting his own son to an aggressive deliverance ritual to cast out the “demon of homosexuality”; he also stages a “night of divine demolition” that promises deliverance and healing, while paying a couple of criminals to help stage the “miracles” in order to deceive the tithing congregation. Building on recent arguments for taking African cartoons seriously for their critical role in public and political culture, I suggest that the cartoons by Àlàbá Ònájìn and the accompanying text by Elnathan John in this graphic novel are an important example of the way in which Pentecostalism, and in particular the figure of the seemingly powerful pastor, is made the subject of satirical criticism.

One could well argue that Pentecostal pastors have been more successful in promoting a reading culture in Nigeria (and beyond) than the whole class of intellectual Men of Letters before them.

Another key example of a critical literary representation of Pentecostalism is Okey Ndibe’s novel Foreign Gods, Inc. This book can be seen as a contemporary follow-up to Wole Soyinka’s The Trials of Brother Jero, which offers a mocking depiction of an earlier generation of Nigerian charismatic prophets. What Soyinka’s character of Brother Jero and Ndibe’s character of Pastor Uka have in common is that they have no ethical values, manipulate and delude their followers, and consider pastoring as a business. Pastor Uka is a typical preacher of the neo-Pentecostal prosperity gospel, and the narrative depiction of him in Foreign Gods, Inc. almost neatly mirrors Obadare’s discussion in chapter 3 of the pastor as a “sexual object” and even a “charismatic porn-star.” See, for instance, this paragraph about Uka entering his church:

The congregation shook with excitement. They stampeded to meet the pastor at the entrance. ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ they sang, young and old alike. They massed around the man, enveloped him. They bawled, hands upraised, like fans at a soccer game.… Had God descended through the clouds and into the shaggy church, the frenzy could scarcely have been more delirious. (Ndibe, 146)

This scene illustrates what Obadare describes as the “Pentecostal erotic economy,” with the pastor at the center and using individual aesthetics and charismatic styles to create a “state of arousal” and emerge as an “ecclesiastical stud” (83, 91). Yet, through other characters, Ndibe voices his skepticism about this erotic economy. Faced with Uka’s fashionable appearance, Ike (the novel’s protagonist) silently names him “peacock pastor” (147). Where his mother believes that Uka is “anointed, a real man of God,” Ike refers to him as “an anointed liar” and “a shameless exploiter of people” (134). Uncle Osuakwu, a traditionalist and priest in the local ancestral shrine, too, sees through Pastor Uka, describing him as “a madman” (194) and as an efulefu, that is, a man “blown about by the wind,” without moral principles (205). Thus, Foreign Gods, Inc. depicts Pastor Uka not just as a charismatic performer of religio-erotic spectacle, but as an embodiment of morally corrupt religious leadership.

Both texts discussed above are literary examples of the tradition of “popular tales of pastors, luxury, frauds and corruption” that abound in Nigeria and beyond. They associate Pentecostalism, and especially the figure of the Pentecostal pastor, with an (im)moral economy of corruption in contemporary Africa.

I don’t have the illusion that writers such as John and Ndibe, or even the giant figure of Soyinka, have an authority in contemporary Nigeria that even comes close to the popularity and influence enjoyed by Pentecostal pastors, so eloquently analyzed by Obadare. In that sense, Obadare is right when he speaks of a “passage of authority” from Men of Letters to Men of God. However, it might be too early to declare the Men of Letters as belonging to yesterday.

Literary Critique of Pentecostalism

Much scholarly attention is being paid to Pentecostal-Charismatic Christianity as a highly public religion, and as a key driver of socio-cultural change in Africa. However, what is often overlooked is how Pentecostalism itself is also made a subject of critique by a range of socio-cultural actors who are concerned about the impact that this form of religion has on society. Literary writing has recently emerged as a major site of critical engagement, with several writers making Pentecostal beliefs and practices a central concern in their texts. Doing so, they stand in, and invigorate, a well-established tradition of critiques of Christianity in African literature.

In the canonical 20th century texts of African literature, such as Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ngugi’s The River Between, Christianity tends to be represented as an agent of colonization and imperial expansion. Yet as Simon Gikandi has pointed out, there is a significant change in post-colonial texts by a new generation of writers: “After independence, Christianity could no longer be represented as a force extraneous to the African experience but a crucial part of the social and cultural fabric of postcolonial society.” This does not necessarily mean that representations of Christianity are more sympathetic, but that a different set of concerns is raised. After all, the face of Christianity on the continent itself has dramatically changed, with the rise of Pentecostalism and its inherent excesses giving contemporary writers new ammunition.

Although Soyinka’s critique is informed by a fundamental skepticism about religion, this is not necessarily the case with a younger generation of writers. Ndibe, for instance, has confessed to have a “profound respect for Christianity and religious faith.” His concern with Pentecostal pastors such as Uka is that they distort “the true meaning of faith.” And to cite another example, of a Woman of Letters this time, the Nigerian writer Chinelo Okparanta, in her novel Under the Udala Trees, explicitly engages in biblical and theological reflection on the question of sexual diversity. She not merely criticizes Pentecostalism for its tendency to “deliver” the queer body from supposedly “demonic” spirits, but creatively reimagines religious thought, with the conclusion of the novel being that “God, who created you, must have known what He did” (these are the words of an initially homophobic mother to her same-sex loving daughter). As much as Okparanta is critical of the colonial, patriarchal, and queer-phobic nature of Christianity in Nigeria, she states to have made “a conscious decision to continue as a Christian.” The same applies to the internationally renowned writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who considers herself a “liberal Catholic.” Thus, what we encounter here is a generation of writers who grew up in the postcolonial era, at a time when Christianity had become very much part of the social milieu, and who combine their criticism of the church with a creative imagination of alternative possibilities of being simultaneously African and Christian. These writers present, not so much a (post)secular critique of religion, but a postcolonial African critical and creative negotiation of religion.

Obadare concludes his book by suggesting that Pentecostal pastors’ rule by prodigy “is not impregnable” (122). Contemporary men and women of letters may not put the nail in the coffins of today’s men (and women) of God. Yet as long as the latter remain popular and powerful, the former are likely to be a thorn in their side and cause some nuisance.