Religious experience has long been a central, and troubled, category in the study of religion. From Rudolf Otto to William James to more recent theorists like Stephen Bush and Ann Taves, a focus on the experiential aspects of religion has been seen as a necessary counterweight to theological trends that emphasize doctrine and textual analysis, and social scientific trends that treat the individual’s experience as a byproduct of wider social and political contexts.

Religious experience has long been a central, and troubled, category in the study of religion. From Rudolf Otto to William James to more recent theorists like Stephen Bush and Ann Taves, a focus on the experiential aspects of religion has been seen as a necessary counterweight to theological trends that emphasize doctrine and textual analysis, and social scientific trends that treat the individual’s experience as a byproduct of wider social and political contexts.

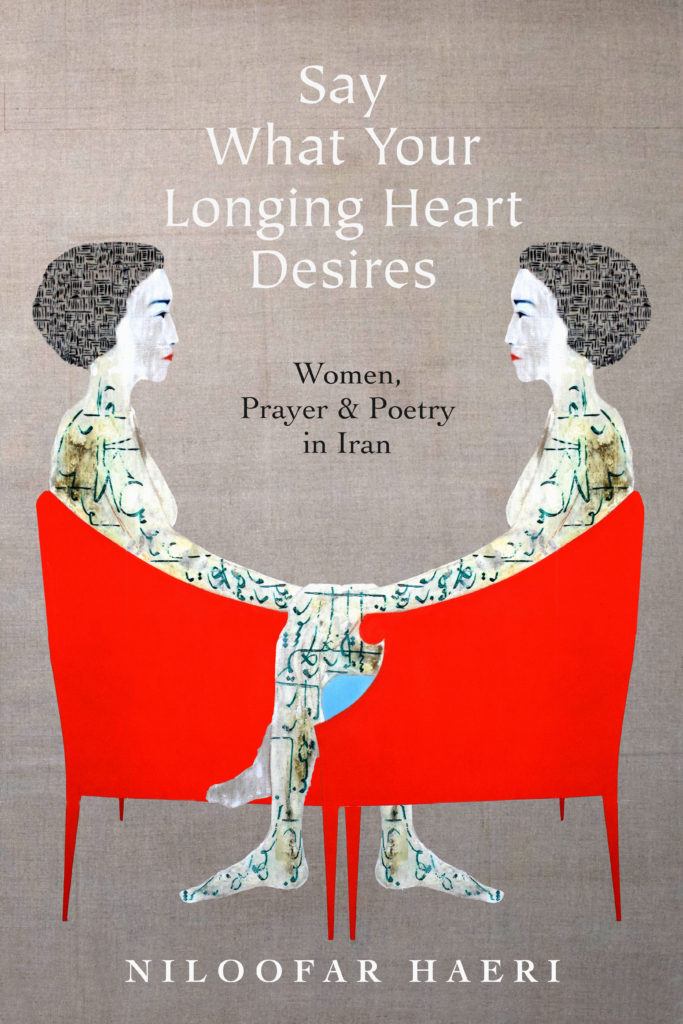

The theoretical wager of Niloofar Haeri’s argument in Say What Your Longing Heart Desires: Women, Poetry, and Prayer in Iran—winner of the 2021 Award for Excellence in the Study of Religion: Constructive-Reflective Studies, sponsored by the American Academy of Religion (AAR)—is that these two modes of analysis need not be seen as diametrically opposed, and that indeed there is dynamism between how individuals practice and personally experience religion and the traditions and institutions that impose boundaries on those practices. Through fieldwork conducted with a group of middle-class Iranian women, Haeri shows how practices of prayer and poetry reading/recitation converge in ways that allow these women to explore a personal relationship with God. Against stereotypes of rote religious practice that one might find in western media—i.e. that Islam is about fulfilling religious obligation without concern for one’s sincerity in doing so—Haeri shows that for these Iranian women, prayer and poetry open one up to the experience of hāl, which can be translated as joy, passion, and awe before God. In describing how the interior lives of these women take shape against the backdrop of an Iranian society still deeply shaped by the 1979 Revolution, Haeri demonstrates that the boundaries between public selves and private selves are never as stark as they seem. Thus, those who only focus on the constraints that discourse, language, institutions, and structure place on subjective action miss how those limits are embodied by flesh and blood human beings. Because humans are embodied creatures they often take up constraints in ways unimaginable to those who designed them. To believe that it is either the individual or social context that is the main driver of change, in other words, is to introduce a false binaristic choice.

Haeri explodes this binary through her sustained attention to both the context in which these women live and their personal experiences. In chapter 1, she outlines the role of poetry in the childhood and adolescent years of her research subjets; in chapter 2, she details both the conventions and contexts surrounding practices of ritual prayer; in chapter 3, she describes the development of do’ā, or spontaneous forms of prayer, carefully laying out how this form of prayer has taken on a more specific meaning following the Revolution; and in chapter 4, she details the development of prayer books over the past decades. In each of these chapters, Haeri trains her attention on how the women in the group study, pray, and recite poetry against this wider social and political background. Prayer and poetry, on her account, allow these women to speak directly to God (even when they are repeating the words of others). It is a medium through which they give voice to the joys, anxieties, and fears they have about family, religion, and many other aspects of their lives.

The collection of essays in this symposium bring a variety of disciplinary expertise to bear on this monograph, and in doing so open up ways of engaging the book that are as dynamic as the text itself. Brenna Moore shows how Haeri’s book might be useful in the classroom for those wanting to counter orientalist stereotypes of Islamic mysticism, especially in its present-day focus on how practices of prayer and poetry recitation are being reappropriated by Muslim women. Kabir Tambar focuses on the challenge that Haeri’s book poses to familiar ways of approaching textual analysis in Islamic studies. Rather than reading the texts that these women draw on, as well as the claims these women themselves make as self-evident, Haeri pushes us to see texts, and the individuals that recite them and pray with them, as dynamic and ever-evolving. This, Tambar contends, forces us to reimagine subject formation beyond a static and sovereign individual. Ahoo Najafian is likewise compelled by the conceptual boundary breaking that Haeri’s text analyzes and theorizes. Najafian focuses on the the shifiting boundary between religion and literature, and suggests that Haeri’s engagement should lead us to further challenge the assumptions built into categories like those of religion or mysticism. Monique Scheer, meanwhile, compares the practices of the women that Haeri discusses in her own work on Protestant Christian religious experience. Haeri’s book, Scheer contends, upends many of our assumptions about what modern religion entails and reveals a closer proximity between the two traditions than have heretofore been imagined. Amy Hollywood mines similar territory, but does so through a recounting of a recent podcast conversation on the topic of Charlotte Bronté’s Jane Eyre. Similar to Scheer, she finds that Haeri’s recounting of these Iranian women’s practices of prayer share more in common than one would expect with Protestant varieties of Christianity. Here, it is prose that provides the means by which to unlock these deeper theological points of connection. Ata Anzali suggests that currents of modernity run underneath the piety expressed by these women in their practices of prayer. These practices, Anzali contends, share more in common with pre-Revolution secularists rather than, as might be assumed, pre-modern religious actors. This is precisely because of their similar concerns with authenticity and self-expression. Finally, Setrag Manoukian begins his essay by offering an account of a conversation with a woman from Shiraz who, like the women in Haeri’s book, finds deep meaning in poetry. He then explores what he calls the “divergent convergence” between prayer and poetry in Iran concerning the role of language, the relationship between rules and desires, and what it means for prayers to be acts of communication.

The issues raised in the symposium go to the heart of the research concerns that animate Contending Modernities. By inviting us to confront our assumptions about what counts as modern religion, and where its origins lie, Haeri’s book again reminds us that accounts of modernity’s development are indeed contentious, and that there is no singular narrative that unites these different strains. Rather than seek unified accounts of modernity and secularization, perhaps we might take a cue from the women Haeri studies to think more capaciously about the sources and theories we draw on in our scholarly practice.