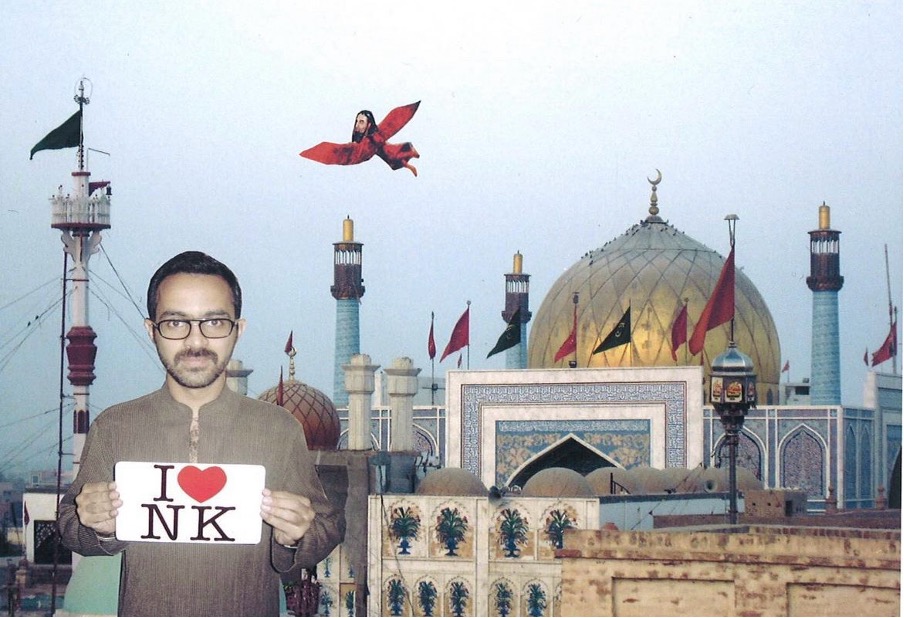

A shrine with a golden dome. A falcon-saint in red. An anthropologist missing home (NK is Neukölln, Berlin). Once a digital postcard from the field, now a companion image. Early on in my research in Sehwan, Pakistan’s most renowned site of multi-faith pilgrimage, I had befriended M. Amin, a photographer-for-hire at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar (henceforth Lal). Our shared practice of photographing in the saint’s durbar, albeit for very different purposes, had led to a jolly routine. Every now and then, for a small fee, Amin would photograph me, then place me in templates popular with pilgrims. Poses, backgrounds, motifs were sometimes of his choice, sometimes on my request, but they were always the result of shared visions. One could also, as I did on this one occasion, include a prop. Possibilities weren’t endless but the digital format afforded malleability. At hand was a small selection of the shrine’s facades over time, and to keep one digital company, a stock of characters—politicians, celebrities, saintly figures.

To re/turn to the image with affect is to consider how the image belatedly affects, relationally informs, makes demands for other knowings. The shrine with the golden dome is a state-run shrine, Shi’i-ascendant in the contemporary, Shivaite in history; the Islamic saint in flight is a shariah-troubling mystic; the homesick anthropologist is doing fieldwork at home. There is also that which provides compositional arrest: the ever-present blue in the image, or what for purposes of this discussion I wish to call out as the affective in-between of the saintly, the stately, and the personal. To see the Pakistani state as a saturating presence at shrines, ordinary as the sky yet back/grounding relations in scenes as saintly, jovial, or arbitrary as this, is to take seriously the state’s affective postures, its felt but less-obvious operations—a line of thinking adjacent to what I term in chapter one of Queer Companions: Religion, Public Intimacy, and Saintly Affects as “infrastructures of the imaginal.” Companionship is that lens through which we can appreciate how objects correlate in situations of co-presence, are altered through adjacency, but also how affect is indispensable to what’s going on in scenes of attachment and scenarios of intimacy. Saint, shrine, state, anthropologist when read in companionable terms reaffirm Chris Ingraham’s observation that affects are “not merely personal, … not merely other. They are in-between.”

Ali in the Elevator

Figuring out the logistics of my fieldwork in Sehwan required at least occasionally that I work my way through state bureaucracy, in this case, the Offices of the Sindh Secretariat in Karachi. One afternoon in June 2012, as I walked into the building’s elevator, the man operating the lift was quick to greet me. Ya-Ali madad, he said, literally, “O Ali, help.” Though revered by all Muslims, Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad counts as the primary imam of Shi‘a Muslims and only fourth of the Rightly Guided Caliphs for Sunnis. And while devotion to Ali can surpass sectarian divisions, summoning Ali as a way of daily greeting is neither ordinary nor expected when it comes to interactions among strangers in Pakistan. Mawla-Ali madad, I responded in no time as was customarily appropriate in this situation. The big smile on the man’s face was proof that things had gone smoothly. I had mastered the response in Sehwan where this form of greeting replaces the otherwise customary salam. Formerly Shivaite and home to 125,000 shrines as per local legend, Sehwan is a densely sacred place. As I note in Queer Companions, it is that location where Shi‘i events, histories, and figures are neither exceptional nor minor, rather deftly interwoven into the warp and weft of the place’s most ordinary rhythms. It is also what makes Sehwan an unstraight location in an Islamic republic of (predominantly) Sunni persuasion. By this I mean that Sehwan’s plural orientations, its fractured heritage and compound sense of the divine do not sit straight with pure, exclusive, or official conceptualizations of Islam in Pakistan. Also, that only in the queer affective weave of the sacred are we able to sense and feel the place’s other histories despite counter measures of governance.

To re/turn to the image with affect is to consider how the image belatedly affects, relationally informs, makes demands for other knowings.

But this was Karachi, not Sehwan. “Looking at your wrist, and your face,” said the man, “I knew at once that you were a mo’min” (a believer). A fundamental belief among the Shi‘a is that Ali is wali, the rightful inheritor of divine wisdom who holds the wilayat (religious and spiritual authority, guardianship) of the Prophet. It is precisely what makes a Shi‘a, mo’min, that is, the one with perfected belief, and superior to the Muslim who merely surrenders to Islam. If my spoken allegiance to Ali had worked wonders, the red thread on my wrist from the shrine of Sehwan was no quiet matter either. In fact, Lal and Ali were companion figures, related by blood, entwined in memory and synonymously invoked by many in Sehwan. A call to Lal was a summoning of Ali. Just as I was beginning to appreciate how a red line on my wrist, thin as thread, was potent enough to tie me to places, histories, and publics beyond the elevator—that it could summon saintly figures, whether called or only inferred—the man inquired further, “So, what is your name?’” Any name but Omar, I thought in the moment, a reference so characteristically Sunni in Pakistan that its reckless disclosure risked fracturing the companionable moment. Struggling to un-name or rename myself, rather clumsily, in haste, and without an ounce of originality, “… Ali,” I exclaimed. More smiles were exchanged as Ali walked out of the elevator.

W/Ali in the World

Wilayat—what counted as shared allegiance to Ali in the elevator—is also that concept of spiritual and territorial authority that makes a wali, an Islamic saint, more than just the sanctified dead in the world. Invoked by Shi‘a and Sufi Muslims in distinct ways, wilayat names a particular confluence of saintly dominion and spatial authority, which “encapsulates the range of complex ideas defining the charismatic power of a saint,” writes Pnina Werbner, “not only over transcendental spaces of mystical knowledge but as sovereign of the terrestrial spaces into which his sacred region exists” (27). The authority and influence ascribed to Islamic saints bear the potential thus to encroach on powers of the state. In fact, as the more-than-living, saints are known to act in and on the world, sometimes as judges who arbitrate conflicts and pronounce verdicts at shrines across South Asia, fittingly called durbars, that is, royal courts or courts of law. Their meddling roles and reputations are part of the reason why shrines can run parallel to projects of the nation-state, or are deemed too close to it when targeted by anti-state actors, or why saints are a worry to the political. Such factors inform the Pakistani state’s motivations to govern saints as well as their shrines.

As part of a modernizing project initiated in the late 1950s, numerous sites of religious significance, especially saints’ shrines, including the one at Sehwan, were eventually nationalized and turned into public endowments. Shrines across Pakistan have since been administered under the Department of Auqaf, a subsidiary of the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Scholars have pointed to the secularizing impulse of such a project but also its political and financial gains. In displacing the authority and curbing the influence of traditional custodians and former caretakers of such sites, the newly-formed state was aspiring to expand its political writ while also gaining access to such shrines’ manifold revenues, material as well as symbolic. Shrines under the state were turned into sites of revenue and cultural tourism, places that offer healing on the cusp of the stately and saintly. More prominent ones were turned into political venues where the state’s vision of Islam could be effectively staged. Administrative measures have also led to inadvertent outcomes, as Alix Philippon has shown. It is under state control that women and transgender individuals have found advanced, if not equal, access to religious ritual, saintly charisma, and spiritual careers—marked by the dual care of the saint and the state, shrines are uniquely positioned at the cusp of the public and the intimate. So long as state control of shrines is accomplished by displacing genealogical claims to saints’ bodies and their heritage, governing saints includes enabling new or other public routes of accessing the saintly. As I have shown elsewhere, state infrastructures have propelled once regional shrines like the one at Sehwan into sites of national prominence and pilgrimage. As visions that are co-authored across the saintly and the stately, projects of national becoming are mediated by religious affect. Multiple publics, however disparate or divergent, are thrown together in national scenes, frames, and routes of attachment through devotion to saints of the state.

Shrines under the state were turned into sites of revenue and cultural tourism, places that offer healing on the cusp of the stately and saintly. More prominent ones were turned into political venues where the state’s vision of Islam could be effectively staged.

More curiously though, even when intent at disciplining the nation’s unruly histories and figures, the state invariably ends up promoting their devotional value and affective appeal. How might we then read the governing tactics and administrative presence of the Pakistani state at saints’ shrines as it spills into affective genres that can be traced only through felt registers? Or, when what pulls people to the saint is also wound up in affective postures and desires of the state? How do we make sense of the common assertion that the state and the saint only act in tandem? Thus, when I argue that affective intimacies with enshrined holy figures, beings, and places can foster unstraight and more-than-inherited ways of being in the world, a key insight of my book, I also point to state infrastructures that make such futures available, if not always attainable. It is only through a cross-reading of affect and governance, reading companionably across pursuits of the saint and projects of the state, that we are able to appreciate the broadly felt means and sometimes disguised desires of the Pakistani state to govern saints as well as to govern with them. The affective in-between is where we feel and thereby know that the Pakistani state is present in scenes of religious intimacy. Here, it haunts images, reverberates through devotional song, and sometimes assumes saintly avatars in dreamworlds, or comes to matter in the odd elevator too. This, to the benefit of my broader argument on public intimacy, reaffirms the idea that as individuals come close to the saintly in Pakistan, they also invariably draw nearer to the state.

One is Known by the Company One Keeps

From my first visit to the pilgrimage town in 2009 to my last in 2018, I have come across reactions to my name that ranged from utter disgust to a preference to not speak to me, from creative ways of addressing me to advice on getting my name changed. In its simplest sense, it evokes a strong dislike for ‘Umar, the second of the Rightly Guided Caliphs for Sunni Muslims and one of the key historical figures blamed by the Shi‘a of Sehwan for his alleged hostility towards the ahl-e-bayt or the family of the Prophet. One of the shrine’s custodians always referred to me as Kasmani to avoid my first name; in one setting, people purposefully kept calling me Aamir, chosen for its similarity with Omar as they later told me. To one fakir, I was Mithall, Sindhi for “the sweet one;” and on a local’s mobile phone, I was saved as Omar-Ali Sehwani. If I wasn’t Ali of the elevator, I was no longer just Omar either. I had been renamed more than once and, more importantly, the place had started to stick to my person—whether as thread on my body or Sehwani in my name. The point is, intimacy alters us; companionship also inflects the ways in which we come to be known and become knowable to the world. With red on my wrist, to the man in the elevator, I simply did not look like an Omar. It is as though like my fakir interlocutors, in coming close to Sehwan, with saintly companions, certain pasts were being forsaken. Other futures were being afforded in intimacy’s bloom.

Further Reading

Ibad, Umber bin. Sufi Shrines and the Pakistani State: The End of Religious Pluralism (2019).

Ingraham, Chris. “To Affect Theory” (2023).

Kasmani, Omar. Queer Companions: Religion, Public Intimacy and Saintly Affects in Pakistan (2022).

Khan, Naveeda. Muslim Becoming: Aspiration and Skepticism in Pakistan (2012).

Khoja-Moolji, Shenila. Sovereign Attachments: Masculinity, Muslimness, and Affective Politics in Pakistan (2021).