There are moments when the entire world seems to shift. The very air around us sizzles and cracks with tension, or maybe anticipation of what is to come. This is the sense and sensibility I get from reading primary sources written at the end of the Great War. This time felt different. Gritty realities of war, widespread illness, and death—along with injustices brought to light through war, illness, and death—made many people see the world with new eyes and believe in the possibility of changing it in unprecedented ways. At the same time, however, hope in the dawning of a new day made way for a thoroughly disenchanted world when change did not materialize. In her book, A Twentieth-Century Crusade: The Vatican’s Battle to Remake Christian Europe, Giuliana Chamedes holds the Vatican’s simultaneous disenchantments and hopes in productive tension.

Historicizing the Vatican’s response to a shifting world, Chamedes asserts “World War I was a moment of great awakening for the papacy” (2). Rather than a conversion of the heart or spirit, this awakening marked a shift in how the Roman Catholic Church understood its place in the world. Observing an increase in the presence and power of secular nation-states, Chamedes argues, the Vatican changed its strategy for global engagement in the short twentieth century. As a new, international world order developed, the Vatican sought to disrupt various modern, secular forces on the one hand (including, liberal internationalism, socialism, and, later, communism) and to “re-Christianize” Europe on the other (32). Such efforts, Chamedes demonstrates, occurred through the Vatican’s “embrace of national self-determination and international law” (3), a move made possible through concordats, which Chamedes defines as “bilateral treat[ies] that would bind the Church and the nation-state together under international law” (3, cf. 31). Forming the basis of “Catholic internationalism,” the Vatican’s use of “concordat diplomacy” allowed the Church to engage in the secular politics of international law even as concordats were positively medieval, a centuries-old tool rebranded as “modern.” This old-made-new diplomatic strategy transformed the Church into a nation-state for the purposes of making a legal agreement recognizable to secular nation-states, but the Church was certainly not born again. Even as the Church completed this legal ritual, it maintained exceptional status as a non-state, religious actor (in the eyes of itself, European nations, and in Chamedes’s text), translating itself in secular terms and acting according to secular norms when desired, yet never losing its religious essence. This allowed the Church to be relevant and powerful in a secular international political system, bolstering the legitimacy of the Church as a political agent and stakeholder in public, civil affairs across Europe, while never ceasing to be a religious institution.

Following the Church from World War I through the end of World War II, Chamedes is careful to recognize the important distinctions within the Vatican, or the “central government of the Roman Catholic Church”; between “the Vatican” and “Catholicism writ large”; and among lay Catholics around the world (9). This precision continues as A Twentieth Century Crusade explains and analyzes the development of Catholic internationalism across Europe, including examples from Italy, Spain, France, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Belgium, Portugal, and Estonia. Along the way, Chamedes makes a significant contribution to the existing literature historicizing and theorizing religion, secularism, and international affairs. Although Chamedes’s work does not draw direct comparisons among religious communities or institutions, A Twentieth-Century Crusade belongs on scholars’ reading lists for comparative religion and history of religion, offering an important historical test case in how a global religious institution imagines and reproduces itself as modern through liberal, secular governance. Chamedes’s work should be of keen interest to scholars of religion and American foreign relations because it widens and deepens the existing literature by associating “religion” in studies of international relations with an ecclesiastical institution, its internal and external intellectual productions, and its engagement with multiple states rather than with an individual, their social community, and personal devotional commitments within the frame of a nation-state. What makes this work so thought-provoking is that it implicitly challenges the popular grammar of and implicit biases for describing and prescribing religion in international relations. The “religious” figure and body in A Twentieth-Century Crusade is not a “faith-based” “non-state actor” seeking to share gospel stories or convert others, but rather a state actor (made possible through the Church and its concordat diplomacy) focused on further developing its legal power and political authority, rather than expressing its religiosity or sharing its faith.

A Twentieth-Century Crusade belongs on scholars’ reading lists for comparative religion and history of religion, offering an important historical test case in how a global religious institution imagines and reproduces itself as modern through liberal, secular governance.

Observing a shift in the political and strategic axis on which the world turned, the Church embraced new terms of engagement. It submitted itself to, and organized itself around, international law, a body of legal texts, a distinct polity, and social reality purported to be the source of its demise. Chamedes replicates the Vatican’s assessment of international law as its “enemy” while demonstrating it was quite the opposite: international law proved to be its saving grace. The grammar and praxis of liberalism gave the Vatican an equal seat at the table of global politics while also reconstructing the way in which the Vatican understood itself. As Chamedes describes, the Church sought to “re-Christianize” Europe. But she shows instead how the Church recalibrated what it meant to be a “Christian” nation in Europe by acting as a sovereign nation-state in relation with other nation-states. Chamedes presents this shift as a means to an end: international law gave the Church greater power against its other enemies, liberal internationalism, socialism, and, later, communism. This twentieth-century “crusade” made the Church modern primarily because it used the law, rather than spiritual weapons, to fight its battles.[1] In this sense, Chamedes strikes an ironic tone with her Crusade: the Church all but solidified a certain notion of the nation-state (“one people, one land, one culture”) as the basic unit of business in the modern political world (7); however, even though Chamedes does not press this point, her work demonstrates how the Church’s efforts also reinforced its Catholic internationalism as the essential form of religion in the modern world. Through concordats, the Vatican taught European nations to hear its voice as the articulation of modern religion, one willing to speak the language of secular international law and self-determination even if its native tongue understood the world in terms that did not necessarily translate. In so doing, the Church legitimized its own “de-privitized” religious authority as more modern than other (presumably, “private”) religions and as a political equal to nation-states.

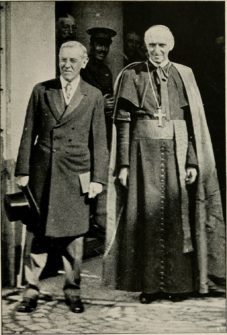

Ironically, US President Woodrow Wilson—a person Chamedes identifies as the Church’s enemy—engaged in a similar strategy as a “crusader for democracy” (while also perceiving the Church to be in opposition to him). He too promoted self-determination as an “intimately religious” concept because it was the product of Providence and, relatedly, necessary for what he imagined to be a proper democratic system of government (i.e. one reflective of Christianity as he understood it). As I and Markku Ruotsila have separately shown, he and his supporters sought to “Christianize” the United States through the liberal processes of secular institutions, especially the formation of the League of Nations as a liberal, secular international institution, a mission and policy agenda that would earn resistance from conservative evangelicals. As Europeans took to the streets in advance of the Paris Peace Conference, many demonstrated their support for “a Wilson peace” with parades, protests, and vigils, and with more than a little help from American propaganda campaigns. Christians around the world appealed to Wilson’s vision in order to insert “religion” into the world’s peace. At the same time, anti-colonial movements the world over seized what historian Erez Manela named the “Wilsonian moment” to adopt and adapt Wilson’s rhetoric to their own ends. Even though the idea of national “self-determination” or a league of nations did not originate with Wilson, he came to symbolize such ideas as a proponent of liberal internationalism and used such recognition as leverage against the Church’s efforts to participate in the Paris Peace Conference and the League of Nations. As I show in A Peaceful Conquest, and Michael G. Thompson also demonstrates, he would ultimately disappoint most of his supporters because he insisted the Paris Peace Conference remain a secular affair among equally powerful nation-states, even as he understood such a move to reinforce his sense of Christian internationalism.

In that sense, A Twentieth-Century Crusade suggests the crusading spirit of the Church was not merely about connecting a Catholic present to a Catholic past via concordats or quelling an external “enemy” found in liberal, nation-states as the Vatican claimed, but also perhaps constructing and asserting a certain and specific social reality among competing Christian powers and authorities. The Vatican was not the only religious or Christian actor intervening in the development of a modern, secular internationalizing world. That Wilson and the Church attempted to do so simultaneously, with diverging senses of “Christianizing,” perceiving themselves as in opposition to each other yet similarly embracing public, secular institutions and rituals is worth further reflection. Each side understood the other as symbolizing a step backward rather than progress for the(ir) “Church.” The “crusade” of Twentieth-Century Crusade, then, is not a “holy war” seeking to reconsecrate Europe after secularization reached a critical mass, as the Vatican claimed, nor to reconcile Christians the world over as historian Phillip Jenkins imagined the Great War. The crusade to “re-Christianize” seems to be aimed at achieving public legitimation of religious authority (that is, in this instance, Catholic authority) by whatever means had the most effective social, political, and religious impact. That the Church saw itself as offering a “religious” and Catholic alternative in the process of utilizing international law and the vocabulary of self-determination bears further consideration for understanding both the history of this era and scholars’ approach to religion in international affairs.

[1] T. Jeremy Gunn, Spiritual Weapons: The Cold War and the Forging of an American National Religion; Jonathan P. Herzog, The Spiritual-Industrial Complex: America’s Religious Battle Against Communism in the Early Cold War; William Inboden, Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment; Diane Kirby, Religion and the Cold War; Andrew Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith: Religion in American War and Diplomacy.