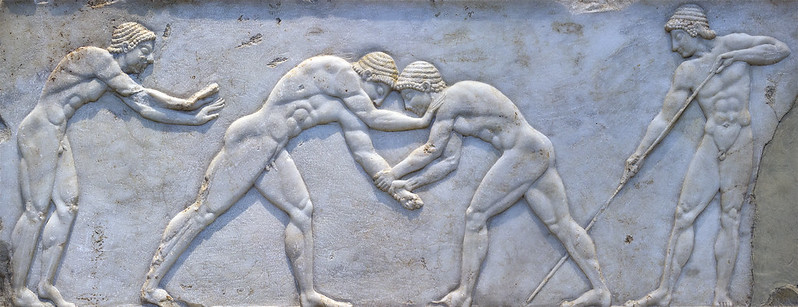

I can only imagine how exhausted Cecelia Lynch must be after Wrestling with God. It is breathtaking in its ambition and at times its audacity. She is constantly circling the subject matter, at times tossing it to the ground, only to find that the subject has thighs of steel and is able to jump to its feet and put Lynch on her heels. I am impressed by her resilience, but also impressed that she never has a moment’s rest, and that is partly because she wrestling from “outside the ring” with others who are “inside the ring.” In other words, who is doing the wrestling is (intentionally) ambiguous. There are the theologians, Christian ethicists, papal authorities, missionaries, Christian-inspired socialists and Marxists, as well as ecumenical intellectuals and activists. All of them are wrestling with God as they also wrestle with secularism and other intellectual currents that challenge their existing worldviews. But standing over this wrestling match is Cecelia Lynch, who herself is wrestling with the very same issues as she watches their contortions, hand-jabs, and leg spins. We learn not only through Lynch’s assured interpretations, but also her own reflexivity. I have considerable admiration for both the book and its author.

Yet a book should be judged not only by how well the author does in answering her own questions, but also by the questions it leaves on the table and subsequently generates. Lynch should be credited for acknowledging that many of the questions cannot be answered precisely because they are subject to heated contestation by this uninterrupted wrestling match, a point I will follow up on below. In that spirit, I want to raise two questions not only for Lynch but for all those who follow in her footsteps.

What Is Christian about Christian Ethics?

I have to start with a fairly remedial question: What is the Christian in Christian ethics? This might seem like a simple question, but as Lynch knows quite well, it is far from simple and is the retaining wall that provides the boundaries for claims to be made about Christian ethics in theory and practice. Christianity is a social and not a natural kind, and all social kinds are heterogenous. Wrestling with God embraces the presumption that Christianity is a social kind and attempts to capture how Christians are wrestling with ethics from differing branches of the faith. We don’t have to worry too much about subgroups within these different branches because presumably they all are part of Christianity, but occasionally there are some branches and some subgroups within these branches that cross the line from Christianity into something else (such as secular humanism). All this is a long-winded way of saying that all social kinds are subject to considerable contestation. Wrestling is the name of the game. Lynch’s neo-Weberian analysis takes much, but not all, of this into account. This leads me to the second question.

Everybody Wrestle?

Only Christians are allowed to enter this match, which presupposes that there are criteria for membership, and these criteria must include beliefs and practices. In other words, there is a screening process. But what questions are included in this screening process? And who referees, deciding which questions are welcome, which answers are heretical, and even who is sanctioned to wrestle? My sense is that Lynch’s analysis begins after all this is settled, but it would be worth saying more about the terms of the settlement. After all, Eastern Christianity does not seem to have made an appearance at the match, and its absence is worth some explanation, especially if it signifies something about its quite different approach to the “other” and the “common good.” In any event, as I read Lynch’s book, I kept wondering what is the core of Christianity and what are the outer boundaries, that is, how far can a Christian venture away from the core without risking being disqualified from participation? Lynch seems to suggest that secular humanism represents the outer limits of the acceptable and constantly risks being transgressive.

As I read Lynch’s book, I kept wondering what is the core of Christianity and what are the outer boundaries, that is, how far can a Christian venture away from the core without risking being disqualified from participation?

A further complication is that Christianity wrestles over different core issues at different times. Lynch is not interested in all features of Christianity but rather its ethics, or rather the ethical purposes of a modernity shaped by Christianity. In other words, Lynch is not addressing pre-modern ethics but rather the Christian attempt to bridge two divides: first, between Christians and less powerful or non-Christian others, and second, between violent and non-violent legitimations of intervention with the goal of bringing peace and social justice. This is a terrific way of approaching the matter because they have not only been at the core of contemporary Christian ethics but also the ethics of many other religious communities as they also confront the challenge of modernity and humanism; in this regard, it provides the basis for important transcultural and transhistorical comparisons.

Nonetheless, I do have some questions, including some that Lynch partially, but does not fully, address. Who are the “others” that have been the most common source of concern for western Christians? My sense is that most of them are non-westerners, mainly those who Christians encountered through exploration, colonialism, imperialism, and missionary work. But this leaves aside the “others” that were nearer and arguably more of a perceived threat to Christians, namely Muslims and Jews. Lynch suggests that western Christians have wrestled with many differentiated others, and it would be worth pursuing how the debate over one other did or did not shape the debate over other others. This would be helpful because Christians have typically ranked others in terms of their proximity to a highly Christian-inflected conception of standards of civilization. Standards of civilization, though, are also subject to change in emphasis and debate. Consider, for instance, Christianity’s entanglement with race; for some Christians, conversion was (almost) enough to warrant admission to civilization, while for others skin color would always hold them back.

Christianity and Modernity

Relatedly, one of the interesting conundrums is how Christian ethics relates to the ethical purposes of modernity. In her introduction to the argument, Lynch proceeds as if they are ontologically distinct. But she later has a long discussion of the complicated relationship between the two, particularly concerning how Christian ethics shaped the very purposes of modernity. And there is also a recognition of how secular humanism has shaped Christian ethics. If both of these are true, is there not a substantial overlap between the two? And does this not mean that it becomes difficult to understand where one ends and the other begins? One way to break this circularity is to consider who, besides Christians, contributed to secular humanism and the separation of the Church and state. Who in Christian societies would have an interest in doing so? There is a case to be made that one “other,” namely European Jews, made important contributions on this matter, and were motivated to do so because of their own theological debates as they increasingly integrated with Christian societies and saw secularism as integral to their physical and ontological survival. In other words, notions of secularism and humanism emerge not only because of internal Christian debates and Christianity’s encounter with non-western peoples, but also because of the active role played by other non-Christian communities in the west.

The Thin Line between Precarity and Collapse

The question of Christianity’s core—and the nonnegotiable elements and boundaries between self and other—also possibly figure into Lynch’s conclusion regarding the permissibility of interventions, coercive and otherwise, to defend and spread Christianity. Said otherwise, how far can Christians go in meeting the other before they lose their faith? Lynch wants her fellow Christians to embrace ethical precarity. As she writes, the radical egalitarianism that she seeks must be based on a “deeply reflexive acknowledgment of ethical precarity.” But at what point does precarity collapse on itself? At what point does radical egalitarianism challenge the Christian self and beliefs? Lynch has a rich discussion of Christian humanitarianism, and one of its interesting developments is the interpretation and place of missionary work and conversion. My research on World Vision International (WVI) suggests that there were various factors that caused the evangelical organization to moderate its tendency to give a bowl of rice alongside a heap of the gospel. Part of this was not just a recognition and respect for the other, but also the sheer fact that WVI grew and became more inclusive of non-western forms of evangelism—and there was not necessarily agreement on which beliefs would become the basis for conversion. But many evangelical Christian humanitarian agencies believe that some people are going to heaven and others to hell depending on whether they have been saved. This is not just a prediction but also a reflection of a belief in the fundamental distinction between self and others. This is not just about saving lives but also saving souls. And if someone believes that I, a Jew, has a damaged soul, then I am going to question their ability to be truly engaged in radical egalitarianism. So, how far can Christians go in their radical engagement before they cease to be Christian in the eyes of other Christians?

Silver Linings?

Lastly, I want to raise the role of theodicy in Lynch’s argument about wrestling. Lynch rightly argues that the problem of theodicy is the reconciliation of the existence of evil in the world alongside the existence of an omnipresent, loving, God. How could a God that cares about his children allow evil to exist? Different religions can be defined by how they answer this problem. Different Christian sects also have a range of views. Theodicy is not necessarily an everyday problem, but rather emerges during times of personal and societal crisis: Why do the good die young? Why would God permit a pandemic? Why would a loving God permit the Holocaust? As Lynch notes, those who experience the problem of theodicy are in need of meaning; if they cannot find meaning, then the suffering is meaningless, and this can be almost too much to bear.

Notions of secularism and humanism emerge not only because of internal Christian debates and Christianity’s encounter with non-western peoples, but also because of the active role played by other non-Christian communities in the west.

The problem of theodicy that arises from soul-shaking experiences, therefore, can create a crisis of faith that requires an answer that restores faith; and this crisis will itself produce an unsettled period during which lay and clergy produce a variety of responses that draw on tradition, but also produce novel interpretations of it. These debates do not happen in abstract but rather in concrete historical contexts that shape which answers are appropriate and practical and which are not. It would have been helpful to her argument and the subsequent chapters, however, if Lynch had even a loose framework for understanding when such change is and is not likely to occur. And it is not always a response to theodicy that drives this change. Consider her discussions of Christian humanitarianism. There were lots of debates among faith-based organizations about how to respond to the post-Cold War challenges and how to do so in ways that were largely consistent with existing practices. But debates did not seem to be triggered or guided by the problem of theodicy. Sometimes the sacred mattered, but faith-based organizations were also moved by profane concerns, such as market shares. In any event, I think that there is more to be said on the subject and I hope that in subsequent work Lynch more clearly connects the specific theodic challenge to the nature of doctrinal and practical change.