One evening before a Bible study, I met with Father (Abouna) James, a Coptic priest in a rural area of middle New Jersey. We sat in what appeared to be the old office of a two-story home, used temporarily as the liturgical space. Abouna James was quite active on Facebook and had recently shared articles on then President Trump’s comments that Haiti and African nations (including Egypt) were “shithole” countries. Looking through the comments on the shared article, I noticed that many Copts voiced their support for Trump’s perspective. I asked the priest why many Copts in diaspora expressed such views on Egypt, despite their Egyptian origins and transnational kin relations. “They support those comments,” he explained, “because when they support them, they are essentially saying ‘shithole’ refers to Islam, not to them.”

While translating “colonial trauma” as well as collective memory of sectarian violence in Egypt, the work of religious differentiation done by some Copts, like those in these comments, gestures toward what I have discussed elsewhere as the ordinary affects of U.S. empire—as a power structure of assimilation to mold sensibilities, relationships, and practices and avoid the gaze of racialized and civilizational suspicion. Both communal and scaled transtemporal affects can be held in tension. These ordinary affects of empire unfold in how Copts have adapted to and have been shaped by visions of Islamic geographies that have kept them in an affective paradox of racial-religious un/belonging. In thinking with the longue durée of geographic and religious difference under colonization, Coptic Christians have more recently integrated into the shifting gaze of racecraft in the United States. The racialization of Coptic Christians in American society can be thought of as pieced together in the ordinary and extraordinary course of everyday doing—mediated through discursive forces of terrorist threat and suspicion of the Middle Eastern other, racial infrastructures of securitization (through profiling programs), as well as the cultural logics that proliferate after the event. The dominance of racial difference—a difference that makes one recognized as a dangerous other—lies in the dense set of prior representations and practices on which they build in U.S. empire—the undocumented, the immigrant, the Jew, Black—the histories of these threats to American freedom and democratic stability interweave with one another. Coptic Christians integrate into the shifting gaze of racecraft in the United States in the way their visibility—as martyrs—is veiled by their positionality as non-White migrants from the Middle East—a politicized place and geography racialized as Muslim and therefore incommensurable with western and specifically American values.

“The Descendent of Islam Princes”

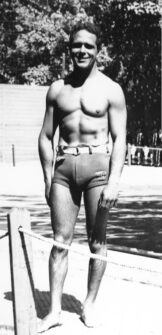

While Coptic immigration from Egypt to the United States began in earnest in the 1970s after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, Egyptian Coptic Olympic diver and Hollywood socialite, Farid Simaika was already in the center of a battle of racial belonging in 1935. At the time, he was engaged to Betty J. Wilson, University of California, Los Angeles co-ed and daughter of William G. Wilson, steel manufacturer from Youngstown, Ohio. When Simaika and Wilson filed an intention to wed notice, the marriage license bureau initially refused to grant them a marriage license because of doubt as to whether Simaika was “an Egyptian or a Caucasian.” The determination of Simaika’s Whiteness was front page news of the Hollywood elite. In pre-Perez v. Sharp (1948) California, existing laws prevented the intermarriage between Whites and “those of another race.” After consulting ethnologists, the county counsel’s office in Los Angeles ruled on April 26, 1935 that “an Egyptian is of the Caucasian race” and that “Egyptians were of the Hamitic and Semitic branch of the Caucasian race,” thereby removing the racial barrier to their marriage.

In her May 1935 article, journalist Adelaide Fielding rhetorically questioned the appeal of Simaika—“Was he [Simaika] not the descendant of Islam princes?” This question is certainly a prime example of Orientalism, (of the amalgamation of different Middle Eastern communities into the figure of “Islam”). Yet, it also connects national imaginaries of racial imperialism to their very real colonial contexts during this time period—when American Christian missionaries and travel writers were plentiful in Egypt and transnationally circulated tropes on Islam and Muslims.

Amid contesting visions of Middle Eastern Christianity and its distance and proximity to Islam at the time, Copts and others had to varyingly contend with European colonial knowledge production on their racial composition and religious kinship with western Christendom. Egyptologists of the late 19th and early 20th century argued that Egyptian Copts were the “descendants of the Pharaohs” and most importantly, that they were “racially pure.” A continual theme was that of the “racial” link between the Copts and the Ancient Egyptians, which sought to distance Copts from their Egyptian Muslims co-religionists. This complex structure of proximity and difference is linked to how Coptic-Egyptians were racialized in the early 20th century United States, and layers of racialization continue to frame the ambiguous character of transnational Coptic life today as well.

While such citizenship strategies in appeals to Whiteness (like that of Simaika) are plentiful in the early 20th century United States out of legal necessity, the affective conviction of difference among Middle Eastern Christian diasporas like the Copts draws from collective memory of sectarian violence in Egypt and upends those contexts translated through a new imperial key. The allure of Trump among the Coptic diaspora in the United States did not start and end with him but exemplifies a long history of paradoxical dissimilarity from and similitude within the global geography of Islam that has bound Christians in/from the Middle East to strategies of distinction as a means of assimilation into Whiteness.

Affective Geographies of Islamic Persecution

Over the past several decades, these colonial binds have been reconfigured into a new kind of American persecution politics that has translated earlier conceptualizations on Islam within it and bound the Coptic diaspora into conservative political orientations. During the Cold War, evangelical narratives of persecution were centered on the suffering of Christians under communism, especially in the Soviet Union. As the Cold War ended, this global vision began to break down. American evangelical persecution politics of the late 20th century fed into diasporic activism and advocacy among Coptic (or Egyptian) Christians in the United States, and reshaped transnational Coptic identity in the process. In this transnational translation, Coptic injury from Egyptian sectarian contexts also lent itself to burgeoning fields of anti-Muslim public discourse.

The affective conviction of difference among Middle Eastern Christian diasporas like the Copts draws from collective memory of sectarian violence in Egypt and upends those contexts translated through a new imperial key.

Along with translating Coptic plight through western vocabularies of legitimacy, Coptic diaspora activists curated an economy of Christian kinship in line with the changing field of the Persecuted Church and evidenced through dissemination of The Copts newsletter (founded by Coptic diaspora activists in the early 1970s). While maintaining Arabic content for the Coptic diaspora that focused more specifically on local contexts in Egypt and their transnational interpretation, the English content of the newsletter evidenced an emerging diasporic Coptic imaginary of persecution politics. In this imaginary, Egypt’s Christians felt the same experiences as other geopolitically important Christian communities, in such places as Sudan and Pakistan, that were also the focus of U.S. foreign policy and evangelical lobbying efforts.

In an anonymous editorial from 1992 entitled “Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing,” a Coptic editor of the newsletter explicitly details how civilizational language operates on a global Islamic geography and through its political affects. Writing about the differences between Islam in the Middle East and how Muslim activists in the west politically organize around it, the editorial reads, “They brag about being Americans, and have the American flag cover the background of their program set. This is the same flag Muslims burn in their daily rituals in Iran, calling America ‘The great Satan.’” In other newsletters throughout the 1990s, the juxtaposition between Islam and America became even greater. In two editorials from 1995 and 1996, a writer by the name of “Victor Mordechai” even describes the Qur’an as an “Islamic Mein Kampf.”

While clearly the work of The Copts in the 1980s and throughout the 1990s was shaped by several emerging discourses on Islam focused on fundamentalism and terrorism, the curation of a Coptic perspective on minority discrimination was directly shaped by experiences from the homeland. Although the dangerous consequences of diasporic Coptic rhetoric on Islam and Muslims should not be overlooked, Coptic immigrants to the United States also channeled their experiences in Egypt of pervasive discrimination and violence into networks of American empire-building, embracing global Islamic geographies of threat and advancing strategies to combat it, placing them into political tension.

Right-wing attention to Coptic conditions in Egypt has historically placed diaspora communities in a contradiction-laden position. On the one hand, drawing attention to the Coptic plight inevitably sets them apart from the broader concerns of the Arab American (or Middle Eastern) communities that are split along religious lines (mainly Muslim and Christian). This attention enhances the fractures that are internal to the body politic that seeks redress for the forms of discrimination and racialization in diaspora, and specifically anti-Muslim/anti-Arab racism pervasive in U.S. society. On the other hand, Coptic calls for American protection or advocacy sets up an unstable synergy between the security this affords and the insecurity it engenders. It places Copts in a contested relationship to other racialized Arab American communities—combatting anti-Arab/anti-Muslim racism—as well as to Coptic kin in the homeland who vehemently disagree with their political tactics from the diaspora. Coptic dependence on such organizations that emphasize religious (and particularly Christian) difference and the evils of Islamic governance and Muslim-majority rule amplify Coptic difference for imperial ends. This is a necessary feature of making Coptic discrimination legible in diaspora in terms of international law and U.S. imperial interests. Over the past several decades, how diasporic Copts have relayed their demands to the U.S. government for equal rights in Egypt became increasingly shaped by new vocabularies and enemies, and securitized discourses on Islam that connected with the initiatives and strategies of U.S. empire and evangelical internationalism. Yet, the pain of the persecuted is curated for Western Christian consumption and ultimately political utility with uneven e/affects—that pain does not produce a homogenous group of bodies who are evenly together in their pain.