Religious studies scholars have traced the history of their field (for instance, see Randall Styers’s chapter “Religious Studies, Past and Present”) from early modernity when the concept of “religion” first emerged as a transcultural category. Into the modern period, the discipline further developed as majority-Christian European and American scholars explored “comparative religion/theology” and “the history of religions” at divinity schools and centers for social science research. In the mid-twentieth century, religious studies scholars undertook concerted efforts to distinguish the field as a discipline separate from Christian theology. Scholars of the field’s history have accounted for this shift by pointing to such factors as the 1960s U.S. Supreme Court school prayer decisions that seemed to permit “teaching about religion” but not “teaching religion” in public institutions (see Sam Gill’s chapter “Territory”), Cold War-era funding sources such as National Defense Fellowships that incentivized religious studies scholars to redefine their discipline as a humanistic endeavor separate from the training of religious ministers, and various Civil Rights and antiwar movements that sparked a challenge to Eurocentrism and Christian normatively in the study of religion (see Mark C. Taylor’s introduction to the linked volume).

During the twenty-first century, the question of the proper relationship between religious studies and Christian theology has remained a topic of intense debate. Differing perspectives have developed around how to respond to this issue. These include the argument that religious studies scholars should work as critics who theorize about theologians and religious discourses without making normative or theological claims themselves. Another view proposes that religious studies scholars should operate as “critical caretakers” who interrogate the relation of religion to power while also constructively engaging marginalized groups and their alternative ways of conceptualizing their traditions. Still another suggests that the field of religious studies might embrace methodological pluralism (see Paul Dafydd Jones’s chapter “‘A Cheerful Unease’: Theology and Religious Studies”) and create space for scholars to account for and discuss their normative—which may include Christian theological—commitments.

As a means of critically examining the history and direction of the field as described above, scholars in the humanities—including Talal Asad, Tomoko Masuzawa, Tisa Wenger, and David Chidester—have analyzed the historical Euro-American-centric, Christian-normative, and colonial dynamics that have shaped both the category of “religion” and the academic discipline that is now known as religious studies. Scholars committed to decolonialization have responded in numerous ways to the continuing legacies of these histories. For example, Tink Tinker has argued that the Euro-Christian concept of “religion” is a colonial imposition that is inherently inaccurate and harmful when used to redescribe American Indian/Native American epistemologies (forms of knowledge). Oludamini Ogunnaike has critiqued the scholarly idealization of “detachment” and “neutrality” that persists within religious studies, and has asserted that the field’s efforts to diversify its topics of consideration in (post)colonial contexts must also extend to the decolonizing of religious/intellectual epistemologies, methodologies, and interlocutors. Contributors to the Contending Modernities blog, particularly writers within the thematic focus on decoloniality, have presented a plurality of perspectives and constructive decolonial proposals addressing the colonial and Christian-normative history of religious studies.

Insights from decolonial theory have raised provocative questions about the basic assumptions of religious studies, as well as the field’s relationship to theology. For instance, what counts as a “religion” and what does the “secular” mean? Who or what determines these definitions? Should all “religions” be thought of as possessing a “theology” or is this term Christian-specific? What (or whose) forms of intellectual production are typically categorized as “theological”—and, accordingly, “subjective”—and which methods of studying religion are considered “neutral” or “objective”? Given Christianity’s historical entanglement with colonialism, how ought decolonially minded religious studies scholars respond in the present to the field’s Christian origins? How might decolonial thought reshape the ways that the boundaries between religious studies and theology, as disciplines, are imagined?

This educational module assembles resources from the Contending Modernities blog that are useful for addressing these questions, raising new ones, and envisioning decolonial approaches to religious studies and theology. The selections below are organized under three overlapping themes: (1) critical explorations of the categories of “religion” and “theology,” (2) perspectives on how scholars might contend with the continuing legacies of colonial Christian theology, and (3) constructive proposals for enacting a decolonial turn. Together, these resources present a plurality of approaches for addressing the field’s Christian-normative and colonial roots, collaborating with ethnic studies and broader decolonial projects, engaging theological/intellectual labor found within religious traditions including and beyond Christianity, and rethinking the role of normative (particularly liberation and decolonization-oriented) claims in academic scholarship. By encouraging a critical assessment of the trajectories of religious studies and theology, these resources challenge scholars to consider the applicability of such concerns within their own work while inviting their participation in the reimagining of the disciplines. Following the module are questions for discussion that teachers and students will find helpful for reflecting on the challenges and possibilities that arise when investigating the relationship between religious studies and theology.

Theme 1: Complicating the Categories of “Religion” and “Theology”

The posts gathered under this theme present three ways of contending with the historical connections between religious studies and Christian theology, particularly concerning the terminology of “religion,” “theology,” and “objectivity.” Together, these posts provoke a reconsideration of the theology/religious studies divide by challenging simplistic narratives that paint theology as “subjective” and religious studies as “objective.” They address the historical intertwinement of the disciplines and contend with the ways that western Christian conceptual categories have shaped the field of religious studies. Rather than assert that religious studies must ensure its more complete objectivity through the rejection of theological influences, the posts under this theme suggest that scholars from both disciplines might critically engage theological resources while acknowledging the limits of theology as a category for approaching non-Christian religious/intellectual traditions.

Religious Studies and/in the Decolonial Turn

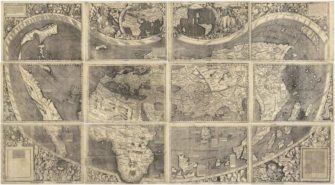

Nelson Maldonado-Torres provides a critical account of the entanglement between the category of “religion” and the formation of modernity/coloniality, writing that religion “emerged as an indispensable term for making sense of the difference between the colonizers and the colonized.” He explains that as the category evolved, “religion” was used first to dehumanize those perceived as not having a religion or culture, and later to mark as inferior those whose religions or cultures were imagined as “primitive” or “irrational.” The dominance of Christian normativity and western notions of secularity shaped both what counted as “religion” (and, accompanying such categorization, which “religions” were valued over others) and what counted as properly “secular” or compatible with modern secularism. This history of the category of “religion” came to inform the forms of scholarship that eventually resulted in the field of religious studies. To contend with this colonial history, Maldonado-Torres argues that religious studies should engage with ethnic studies and other decolonial efforts inside and outside the academy.

Considered with respect to the relationship between religious studies and theology, Maldonado-Torres’s analyses and proposals invite critical questions about the “secular” and “religious” categorizations that have been taken as distinguishing the disciplines from one another and defining the scope of their inquiries. Rather than assert its compatibility with modern secularism in comparison to theology, religious studies might—by drawing from its own resources for destabilizing “religious” and “secular” terminology—contend with the ways that Christian-theological and European-colonial concerns have shaped its development and continue to shape the organization of secular, modern/colonial worlds. Since processes of religious category-formation have been imbricated in processes of racialization and colonization, it is crucial for religious studies and theology scholars to consider the relevance of decolonial analysis for their work and to recognize the unique perspective that scholarship on “religion” and “secularization” can offer to decolonial thought.

“The Dead Don’t Go Anywhere”: Phenomenology, Religious Studies, and History

Joshua Lupo’s account of the history of religious studies in this post highlights the role of Christian theology at the field’s origins, as well as more recent efforts by religious studies scholars to distance themselves from Christian theological assumptions and to maintain a sense of scholarly detachment in relation to their topics of study. Lupo focuses on the phenomenological methods emphasizing “subjective experience” and “meaning” that were prominent during the formation of religious studies—particularly as employed by European Christian theologians studying “world religions”—and the critiques of such methods as merely advancing Christian theological worldviews. He writes that in the present, many efforts to separate religious studies scholarship from theology have involved the suspicion of phenomenological methods and the idealization of a stance of scholarly detachment and objectivity. This stance, however, is an always-unachievable position, and prevents religious studies from acknowledging its past and imagining new paths for critical work. Lupo proposes a critical reappropriation of the insights of phenomenology as a means of challenging this idealized stance, and of “contribut[ing] to philosophical accounts that prioritize the agency of the marginalized who challenge racism, coloniality, and misogyny in our politics and culture.”

Lupo’s discussion in this post is useful for considering the goals and limitations of a strict religious studies/Christian theology separation, and for exploring possibilities within the theological residues of religious studies that this separation causes scholars to overlook. This post suggests that, rather than avoid “theological” or “subjective” resources, religious studies scholars might explore the history of their field and acknowledge the impossibility of maintaining a purely “secular” and “objective” position. Lupo’s argument for the recovery of certain phenomenological insights opens new pathways for the critical engagement of Christian theological sources, alongside sources from non-Christian religious/intellectual traditions and from anti-racist, decolonial, and feminist thought.

Taking a Critical Indigenous and Ethnic Studies Approach to Decolonizing Religious Studies

Natalie Avalos critiques the racist and colonial dynamics that continue to persist within religious studies. She draws attention to the ways that Native American and Indigenous religious traditions have historically been dismissed as failed epistemologies or excluded from recognition as “true” religions. She also writes that the field of religious studies has tended to separate itself from the discipline of theology and from the normative goals of liberation theology, which “as a praxis is directed at both religious and material liberation.” Avalos situates her own work as resonant with yet distinct from liberation theology, drawing primarily from Native American and Indigenous studies and rooted in decolonial frameworks. She critiques the category of “theology” as inadequate for discussing non-Christian traditions, and she positions her own scholarship as intentionally resisting categorization as such. Despite these efforts, she writes that her work has been critiqued as “too theological” for the field of religious studies—a designation rooted in the field’s historical prioritization of etic forms of analysis (which employ theoretical apparatus external to the community whose religious phenomena are being analyzed) over emic ones (which prioritize the terminology and conceptual understandings of a particular community) and tendency to distance itself from normative claims. Avalos critiques the ways that the Protestant secular has influenced both what counts as “religious” and what counts as “objective” religious studies scholarship, and she proposes critical ethnic studies and decolonial approaches as resources for challenging colonial/Christian theological logics.

Like Maldonado-Torres’s post, Avalos’s post critiques the colonial entanglement of religious category formation, and like Lupo’s post, this essay pushes back against the idealization of “objectivity” within religious studies. By focusing specifically on Native American and Indigenous religious traditions and epistemologies, Avalos advances a dual critique. First, she challenges the uncritical application of Christian-influenced conceptual categories such as “theology” to non-Christian traditions, while simultaneously acknowledging the usefulness of “religion” as a (constructed and imperfect) category in her argument that Indigenous epistemologies should be taken seriously by the field of religious studies. Next, Avalos critiques assumptions of a “secular/religious” binary and the devaluing or delegitimization of scholarship that has been categorized as “theological” and therefore “subjective.” Avalos’s post invites both a rethinking of the boundaries between religious studies and theology, and critical reflection on the implications of labelling of non-Christian epistemological traditions as “religious” or “theological.”

Theme 2: Challenging Colonial Christian Theology

Assembled under this theme are three posts that offer contrasting proposals for scholars aiming to challenge colonial Christian theology. Together, they highlight the importance of centering analyses of race and empire, contending with the entanglement of Christian theology with Eurocentrism and colonial legacies, and challenging Christian normativity within religious studies. Atalia Omer’s post offers a necessary reminder that Christian theology is not monolithic and that valuable decolonial resources can be located within marginal traditions of Christian thought and practice. Considered alongside Nicholas Anderson’s and Santiago Slabodsky’s posts, however, it is evident that even scholarship on anti-oppressive forms of Christianity must take care to avoid replicating the dynamics of Christian hegemony.

Empire and Race in Comparative Religious Ethics

Nicholas Anderson describes comparative religious ethics as a subfield committed to the provincializing of Christian and/or European philosophical concepts and moral vocabularies, asserting that this provincializing—while valuable—does not in and of itself constitute a decolonial turn. Anderson argues that comparative religious ethicists must learn from decolonial theorists by intentionally analyzing the influence of imperial and racial formations on people’s ethical lives. This involves contending with the colonial histories of the very categories of “ethics,” “religion,” “personhood,” and “reason” that have grounded the discipline’s practice, and the adoption of a willingness to interrogate and even abandon core assumptions of the subfield. He concludes by gesturing towards constructive proposals for a truly decolonial turn in comparative religious ethics, suggesting that new modes of ethical inquiry produced through a greater attention to race and empire would likely draw from “sources and/or practices that many comparativists have not heretofore considered “religious” or “ethical.””

By avoiding a conflation between the decolonization of comparative religious ethics and the decentering of Christian thought within the subfield—even as he views the latter as essential for decolonial projects—Anderson’s post invites a deeper exploration of the steps that religious studies scholars might take to advance decolonial work. His discussion also raises questions about possibilities for the field of theology to similarly center analyses of empire and race, and to decenter European philosophical concepts and moral vocabularies—as well as questions about the extent to which the field of theology is capable of contributing to efforts to challenge Christian normativity.

Not Every Radical Philosophy is Decolonial

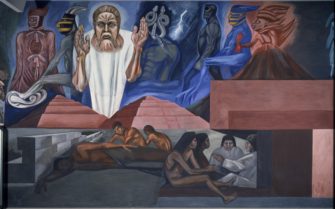

Santiago Slabodsky discusses the 1550–1551 Valladolid debate in which European Christian theologian-philosophers—who could imagine “no possibility of existence outside a totalizing Christian framework”—were tasked with determining the “nature” of Indigenous peoples. He traces how the legacies of pivotal colonial moments such as this debate fueled Christian evolutionist genocides and extended into the creation of academic disciplines for the study of religion, including the area of philosophy of religion, which has continued to betray tendencies towards Christian normativity. As a result, the contestation of Christian hegemony and the provincializing of Christian thought—including “its secular reiterations”—appears for Slabodsky as the first step towards decolonizing the philosophy of religion. He proposes that rather than uphold colonially sanctioned forms of dissent (that is, forms of radical philosophy that are rooted in—and accepted as legitimate by—the side of the colonizer) or continue to sustain the dominance of Christian frameworks, scholars of philosophy of religion should “think from, and with, critical thought emerging from barbaric (rejected, negated, or invisibilized) cosmovisions.”

Like Maldonado-Torres and Avalos, Slabodsky discusses the ways that dominant Christian frameworks have shaped the development and application of ontological and epistemological concepts within religious studies. Slabodsky warns against the maintenance of Christian normativity as it appears even in resistant forms of scholarship in/on religion, and he argues that the tendency “to follow the critique that the secular is not a neutral space in order to intervene in public debates with normative Christian resources instead of delinking from them” evidences a failure to sufficiently confront totalizing Christian frameworks. He also cautions against overly optimistic interpretations of the role of Bartolomé de las Casas in the Valladolid debate, reframing the debate as a moment in which colonialism was reinforced rather than interrupted. His post ultimately calls for the acknowledgment of colonial difference through engagement with cosmovisions that have been the target of epistemological genocide. Although Slabodsky writes that some forms of Christianity can offer useful resources for decolonial projects, his post raises critical questions about the place of Christian thought within broader efforts to decolonize religious studies and theology.

Decolonizing the Practices of Religion in International Relations

This post is a part of a book symposium on Cecelia Lynch’s Wrestling with God: Ethical Precarity in Christianity and International Relations (2020), which provides a sweeping genealogical exploration of the role of Christian traditions in shaping the modern field of international relations and reveals plural forms of ethical reasoning within Christian thought. (For a more detailed summary of the book, refer to this introduction to the book symposium.) Atalia Omer, in response to Lynch’s work, discusses the relationship between western Christianity and secular modernity and echoes Lynch’s critiques of European/Christian colonialism. Omer praises the book for bringing nuance to such critiques by emphasizing the internal diversity of Christian thought and advancing an intersectional approach to religion and politics. She elaborates on the book’s value for challenging overly simplistic or reductionistic accounts of Christianity’s entanglement with colonialism.

In contrast to Slabodsky’s critiques, Omer’s post emphasizes that Christianity should not be imagined as a “foil for decolonial epistemologies”; rather, scholars committed to decolonization ought to think of “religion,” “race,” and “gender” together and attend to “the epistemologies of those on the Christian margins.” Omer’s work suggests that decolonial scholarship in religious studies should recognize Christianity as a heterogeneous body of thought that has offered communities anti-oppressive resources. While Slabodsky’s and Anderson’s posts reveal that religious studies” Christian-centric colonial past and present reliance on Christian normativity is still in need of critique, Omer’s post highlights the importance of considering marginal Christian epistemologies and engaging decolonial Christian-theological resources.

Theme 3: Towards Decolonial Sources, Epistemologies, and Practices

The blog posts in this section provide decolonial approaches to intellectual production by drawing on religious and theological traditions. The first theme of this educational module focused on complicating the theology/religious studies divide and notions of “objectivity,” and the second challenged Eurocentrism and colonial Christian hegemony. This final theme offers constructive decolonial proposals for scholarly approaches, interlocutors, and questions that might be explored in response to the critiques advanced within the first two themes. Together, the posts under this theme propose ways that non-Christian and non-European sources might be engaged seriously and on their own terms through a decolonial lens, with implications for research, teaching, and scholarly conversations in religious studies and theology.

Decolonizing Religion: The Future of Comparative Religious Ethics

In this post, Irene Oh offers constructive proposals for decolonizing the subfield of comparative religious ethics. Although she discusses the ways that scholars have already begun to decenter Christianity and dismantle notions of Christian supremacy, she identifies a need for a decolonial questioning of the terms and assumptions at the core of the discipline. Oh briefly refers to the history of the category of “religion” as a European Christian invention that has served colonial ends, and she mentions critiques of the “commonly accepted definition of ethics as other-regarding.” She argues that one step towards decolonizing comparative religious ethics would be to avoid inaccurately imposing terminology or forcing “the moral relevance of issues” transculturally. At the same time, she suggests that dialogue among communities may result in a shared understanding of issues and ideas that resonate across different contexts. Ultimately, she asserts that a decolonial turn within comparative religious ethics would involve recognizing non-Christian and non-European peoples as intellectual and moral agents rather than as objects of study, and uplifting the ways these agents “represent ideas on their own terms, rather than mediated through the theories and categories of colonialism.”

If applied to the relationship between religious modes of intellectual production and the field of religious studies, Oh’s post invites reflection on the different ways that Christian theologies and non-Christian moral and epistemological traditions might be approached by scholars in various religious studies subfields. Lupo’s and Avalos’s posts have critiqued the idealization of scholarly “objectivity,” and Avalos has argued for Indigenous epistemologies and normative decolonial claims to be taken seriously within religious studies. Similarly, Oh’s post insists upon the recognition of moral and intellectual claims made by non-Christian and non-European interlocutors; however, the post’s emphasis on dialogue and intellectual humility also raises questions about how a scholar might navigate their own normative commitments when engaging in transcultural conversations.

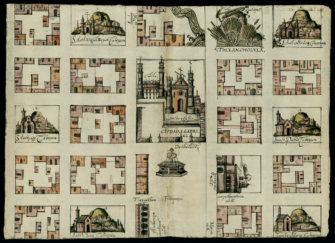

The Promise of Decolonization for the Study of Religions

The decolonial approach that Abdulkader Tayob offers in this post counters the Eurocentrism of the humanities. Tayob critiques the ways that the field of religious studies seems to contest the intrusion of theological assumptions and methodologies more than it challenges its own colonial assumptions and entanglements, and he argues that religious studies must dismantle its “colonial library” as one step towards decolonization. To do so, he proposes that the distinction between the scholarship of the colonizers and the scholarship of the colonized be acknowledged, and that the latter receive the attention that it has previously been denied. In particular, Tayob argues that critical thought from within Islam and other religious traditions—types of intellectual labor that have not always been treated as legitimate within the academy—must be taken seriously as forms of scholarship, and that practices of “critique” should not be imagined as limited to the modern secular modes that are presently dominant. Noting that the critical reflections of scholars such as Talal Asad have ironically been taken up in service of western-centric scholarship on religion (and have thus been used to accentuate—rather than displace—the “colonial library,” Tayob also argues that the types of inquiry pursued by religious studies scholars should increasingly prioritize the social and political contexts of the colonized, rather than the contexts inhabited by western scholars.

The decolonial approach offered by Tayob emphasizes self-criticism, dialogue among secular and religious critical voices, and the de-exceptionalizing of the western academic tradition. Tayob’s proposals may open space for religious studies scholars to approach religious/theological modes of intellectual production on their own terms, and to respect non-western and non-Christian religious critical voices as interlocutors. Additionally, Tayob’s emphasis on resisting “colonial libraries” invites scholars to engage decolonial sources in their research and teaching. This emphasis raises questions about the ways that religious studies scholars might balance the critical reappropriation of “canonical” resources– as Lupo’s post proposes—with the necessity of assembling an alternative “library.”

Is Decolonial Theory Secular?: Lessons from Frantz Fanon

Nelson Maldonado-Torres writes that decolonial theory is not a mere extension of mainstream postcolonial studies, but a transdisciplinary and ongoing mode of thought, practice, and being that has historically involved an openness to religious thought, attention to the role of spirituality for decolonial projects, and commitment to critiquing the coloniality of modern western secularism. He asserts that narratives framing the engagement between decoloniality and religion as a “new” development are inaccurate and serve only to reinforce the coloniality of the secular academy. Next, Maldonado-Torres turns to the life and thought of Frantz Fanon to counter the ways that Fanon has often been framed as opposed to religion. Drawing out five lessons from Fanon, Maldonado-Torres explores the relevance of Fanon’s work for envisioning relations among religious studies, religious thought and practice, and ongoing processes of decolonization.

By both highlighting aspects of Fanon’s work that reveal signs of openness to religion and theology, and imagining an expansion of Fanon’s thought in ways that Fanon himself had not considered (for instance, by mentioning practitioners of African diaspora spiritualities who have drawn from Fanon’s work), Maldonado-Torres’s post exemplifies one method through which scholars of religious studies and theology might incorporate insights from decolonial thought, and in turn, enrich decolonial projects with resources from their own fields. This post shows that figures from decolonial thought—including figures that are traditionally imagined in opposition to religion and theology—might act as unexpected interlocutors and inspire a reshaping of the canons and considerations of the disciplines.

Conclusion and Discussion Questions

The blog posts assembled for this educational module have addressed the history of religious studies and categories such as “religion” and “theology,” discussed the role of efforts to decenter Christian and/or European thought for broader decolonial projects, and offered constructive proposals for decolonizing scholarly approaches to sources, terminology, methodology, lines of inquiry, and chosen interlocutors. The questions below trace some of the overarching themes among the authors, draw out some standing debates and considerations, and provide a means of continuing conversations on this topic.

-

Contending with Christianity

Atalia Omer challenges overly simplistic and reductionistic accounts of Christianity’s relationship to colonialism and argues for the importance of taking an intersectional approach that attends to marginal Christian epistemologies. Santiago Slabodsky, while noting that some forms of Christianity can provide decolonial resources, critiques the dominance of Christian normativity “in discourses of dominance, rebellion, and re-existence.” In what ways might religious studies scholarship that centers marginal Christian epistemologies (for instance, “popular Christianities,” liberation theology, and anti-colonial Christian movements) and decolonial Christian resources contend with the field’s Christian-centric colonial past and avoid reinforcing Christian normativity? How might scholarship in the field of Christian theology address these concerns?

-

The Colonial Past

Joshua Lupo’s post offers proposals for religious studies scholars to contend with—and critically reappropriate—methods and figures from the field’s past. Abdulkader Tayob’s post emphasizes the need for religious studies scholars to dismantle the “colonial library” at the heart of the field. In different ways, both of these authors trouble the boundaries that have been constructed between strictly“secular” religious studies scholarship and the theological/intellectual labor found within religious traditions. In what ways might their proposals complement or conflict with each other? How might decolonial approaches to religious studies both critically reappropriate resources from the field’s formative colonial past, and assemble a new decolonial “library”? How might these efforts reshape the ways religious studies scholars relate to religious/theological intellectual production?

-

Negotiating Religious Values

Natalie Avalos and Joshua Lupo—from different angles—critique the scholarly idealization of a stance of detachment and objectivity. Such critiques might be valuably directed towards the troubling of “neutrality” and towards the opening of religious studies to the types of liberation-oriented, decolonizing projects that Avalos uplifts. On the other hand, Irene Oh and Abdulkader Tayob both discuss dialogue as a component of a decolonial turn. The forms of dialogue that these authors propose involve approaching (particularly non-Christian and non-European) religious practitioners as intellectual/moral agents: potential interlocutors rather than mere data or objects of study. Such an approach appears to involve some bracketing or provincializing of one’s own ethical/moral vocabularies and intellectual traditions. How might decolonial projects within theology and religious studies balance normative (liberation and decolonization-oriented) claims with the intellectual humility that dialogue involves? Or, in what ways might different types of decolonial projects negotiate these values differently?

-

Beyond the Field

Nelson Maldonado-Torres and Natalie Avalos both argue that religious studies should welcome insights from critical ethnic studies and broader decolonial projects from within and outside of academia. Relatedly, Nicholas Anderson writes that a decolonial turn within comparative religious ethics would entail transformative analyses of race and empire and a willingness to engage with sources beyond ones that are typically considered “religious.” Maldonado-Torres’s posts suggest that ethnic studies and decolonial projects might “gain much from the analyses and insights of decolonial Religious Studies, decolonial philosophy of religion, and decolonial forms of religious thought and theology.” What perspectives, contributions, and creative reworkings do—or might—religious studies, theology, and religious thought uniquely offer to decolonial discussions and projects?

Bibliography and Further Reading

Asad, Talal. “The Construction of Religion as an Anthropological Category.” In Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam, 27-54. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Chidester, David. Empire of Religion: Imperialism and Comparative Religion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Gill, Sam. “Territory.” In Critical Terms for Religious Studies, edited by Mark C. Taylor, 298-314. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Jones, Paul Dafydd. “‘A Cheerful Unease’: Theology and Religious Studies.” In Religious Studies and Rabbinics: A Conversation, edited by Elizabeth Shanks Alexander and Beth A. Berkowitz, 69-81. London: Routledge, 2017.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

McCutcheon, Russell T. Critics Not Caretakers: Redescribing the Public Study of Religion. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001.

———. “‘Just Follow the Money’: The Cold War, the Humanistic Study of Religion, and the Fallacy of Insufficient Cynicism.” Culture and Religion 5, no. 1 (2004): 41-69. doi:10.1080/0143830042000200355.

Ogunnaike, Oludamini. “Expanding the Menu or Seats at the Table? Grotesque Pluralism in the (post)Colonial Philosophy of Religion.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 89, no. 2 (June 2021): 729-738. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfab049.

Omer, Atalia. “Can a Critic Be a Caretaker too? Religion, Conflict, and Conflict Transformation.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 79, no. 2 (June 2011): 459-496. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfq076.

Styers, Randall. “Religious Studies, Past and Present.” In Religious Studies and Rabbinics: A Conversation, edited by Elizabeth Shanks Alexander and Beth A. Berkowitz, 25-38. London: Routledge, 2017.

Taylor, Mark C. Introduction to Critical Terms for Religious Studies, 1-19. Edited by Mark C. Taylor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Tinker, Tink. Osage Nation / Wazhazhe Udsethe. “Religious Studies: The Final Colonization of the American Indian.” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 19, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 380-390.

Wenger, Tisa. We Have a Religion: The 1920s Pueblo Indian Dance Controversy and American Religious Freedom. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.