President Trump’s comment last week that American Jews who vote for the Democratic Party are being “greatly disloyal” has sent shock waves through the Jewish world. What did he mean? Disloyal to whom? Isn’t the accusation of disloyalty an anti-Semitic dog whistle? By not initially defining the object of “disloyalty” Trump opened up various possibilities of how his comment can, or should, be parsed. Groups on the Jewish left such as Jewish Voice for Peace and J-Street to the center-right AIPAC contested this statement. President Rivlin in Israel contested this statement. The Likud-led government said nothing. The overt partisan overtones of the comment resulted in Jewish Trumpists defending the president, saying that, even if the comment may have been poorly articulated, American Jews who vote for “the party of Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar” (this is how Trumpists are reconstructing “the Democrats”) are being disloyal to Israel and, given the current fusion of pro-Israelness and allegiance to the Jews, are being disloyal to the Jewish people.

Critics of the comment claim that the language of disloyalty is anti-Semitic. The problem is that in this case the “dual loyalty” equation implied in Trump’s “disloyalty” locution seems to be inverted. The anti-Semitic trope of dual loyalty has historically been used to claim that the Jews are being disloyal to their country of residence in favor of their loyalty to the Jewish people. Later, the question of loyalty extended to the state of Israel. In the late 18thcentury, the question of Jewish loyalty was posed to the Jewish sages in France in the wake of their emancipation. Could the French Jews, who ostensibly had loyalty to another collective (the Jewish people), ever be fully loyal to France? The French sages responded that the Jews are a people of a religious tradition and not a nation and thus fidelity to the Jewish people does not stand in contradiction to allegiance to the French nation. On this basis they were emancipated.

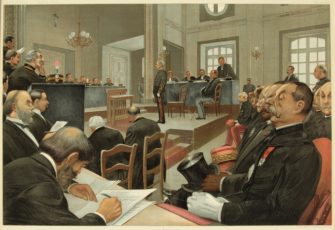

This precarious equation lasted until it exploded with the Dreyfus affair in 1894 when French officer Alfred Dreyfus was accused and convicted of treason. (The conviction was later overturned.) A young Viennese journalist named Theodore Herzl covered the story and heard the reactions of many French men and women who were convinced of Dreyfus’s guilt. These men and women claimed that Dreyfus, as a Jew, could never give full allegiance to France. In some way, this gave birth to Zionism, which claimed in part that even the fully assimilated Dreyfus’s of the world will never be accepted as full citizens in their country of residence. That is, Jews could never fully shed the suspicion of dual loyalty.

While “dual loyalty” is indeed often an anti-Semitic canard, it is also a real challenge to all of Diaspora Jewry, especially after the establishment of the state of Israel. What is meant, for example, by the 1990s bumper sticker, “I Love New York but Jerusalem is My Home”? What if a passerby said to the driver of a car with such a sticker, “Go home”? Would that be anti-Semitic? In a way, yes it might be, but what about the bumper sticker itself, what is it trying to convey? Today, what does “home” refer to if not the capital city of another country? My point is that if Jews reflexively claim that the accusation of “dual loyalty” is anti-Semitic, we too easily ignore that it was, and remains, one of the great challenges of Jews in modernity.

Here is an example: I have friends—Modern Orthodox Jews—whose son was considering enlisting in the U.S. Navy. Almost everyone he shared his plans with at a Shabbat Kiddush said to him, “If you are going to serve in the army, why not join the IDF?” His response was, “because I am an American.” But what was behind the response of these American Orthodox Jews to this young man? “If you are going to risk your life,” they may have been thinking, “why do it for the U.S.? Why not do it for Israel?” Is this an instance of dual loyalty? If we deflect all accusations of dual loyalty, we miss the ways we practice it all the time.

Trump’s comment on Jews’ “great disloyalty” wasn’t accusing Jews of dual loyalty; in fact, he was suggesting Jews are not exercising dual loyalty enough! Can we thus say that this isn’t anti-Semitic at all? Yes. And no. In the wake of Trump’s comment, at a Close the Camps rally of liberal American Jews held outside Farmington’s Holocaust Memorial Center near Detroit, a white supremacist counter-demonstration showed white nationalists waving an American and an Israeli flag. White supremacists, whose worldview emerges from the KKK and other like-minded groups, are waving the Israeli flag to protest against liberal American Jews. Is there a connection between Trump’s comment and this phenomena?

One way to understand this is to look back at the American Zionism of Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis. In the teens of the 20th century when most American Jews were at best ambivalent about Zionism, precisely because it exacerbated the anxiety of dual loyalty, Brandeis stood as a proud Zionist. But Brandeis deeply understood the challenge Zionism posed to a Jewry desperately trying to become “American.”

In a lecture “The Rebirth of the Jewish Nation,” Brandeis said the following:

My approach to Zionism was through Americanism. In time, practical experience and observation convinced me that Jews were by reason of their traditions and their character peculiarly fitted for the attainment of American ideals. Gradually, it became clear to me that to be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.

In another essay “The Jewish Problem: How to Solve It,” presented to the Conference of Council of Reform Rabbis in 1915, Brandeis wrote:

Indeed, loyalty to America demands rather that each American Jew become a Zionist. For only through the ennobling effect of its strivings can we develop the best that is in us and give to this country the full benefit of our great inheritance. The Jewish spirit, so long preserved, the character developed by so many centuries of sacrifice, should be preserved and developed further, so that in America as elsewhere the sons of the race may in future live lives and do deeds worthy of their ancestors.

The fusion of Americanism and Zionism for Brandeis was his way of allaying the fears of dual loyalty among many progressive era American Jews. While I am quite certain Trump does not know of Brandeis’s Zionism, and Brandeis certainly did not intend his Zionism to be blind allegiance to a Jewish state (his Zionism was not even promoting a Jewish state), I think Trump is inadvertently using Brandeis’s logic to make two points. First, on Trump’s reading, American Jews are being disloyal to their people if they do not give full allegiance to the state of Israel and its government (Brandeis, of course, lived long before the state of Israel). And second, that such disloyalty is also disloyalty to America since, as Brandeis said, “to be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.”

So when those white supremacists waved an Israeli flag to protest against an American Jewish protest against detention centers in a Detroit suburb, the flag wasn’t about being pro-Jewish (one could reasonably assume some hold anti-Semitic views) or even pro-Israel in any conventional way. It was pro-American. Thus American Jews who support “the party of Tlaib and Omar” are not only disloyal to their people. They are also disloyal to America. Thus Trump’s inversion of the “dual loyalty” equation does not erase its anti-Semitic connotations; it merely recalibrates its implications. Watching white supremacists waving an Israeli flag, as jarring as it may look, is therefore not dissonant at all.