The dominant templates for the designs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination exhibit come from two different Catholic figures, the church’s ordained men (the clergy) and its angels. These two groups belong to what the curators call the “earthly” and the “celestial” hierarchies of Catholic tradition. The “heavenly bodies” in question are both ‘up there’ above and ‘down here’ below. The treatment of the first of the hierarchies, the celestial, is somewhat limited in the exhibit. This group—made up, according to Pseudo-Dionysius’ rendering, of the Councilors, Governors, and Ministers of Heaven—is represented at the Met mainly by its lowest-ranking members, the angels. The curators explain in the exhibit’s wall text that angels “feature most prominently in the imagination of fashion designers” because they “function as guides, protectors, and messengers to humans.” They have been a staple of Catholic art over the centuries. Borrowing from these referents, the exhibit includes a choir of angles standing far above the floor of the main hall. An adjoining hall features another cluster of angels. One or two angel-like figures hover over doorways, other impressively winged angels occupy prominent positions. They are gendered, almost exclusively, female.

But the real emphasis of the exhibit rests on pieces inspired by the church’s earthly hierarchy—a group that the curators tell us is made up of priests (of different ranks and religious orders), bishops, cardinals, and popes as well as “nuns and monks” who have elected a “deliberately modest position” (they leave out deacons). The existence of this clear earthly hierarchy is a boon to the fashion designers, who capitalize on the church’s eagerness to use dress to “reflect and reinforce divisions based on rank and gender.” A good number of the designs reference the habits of women religious, particularly habits that were more commonly worn before the late 1960s. More prominent, however, are pieces inspired by priests’ liturgical wear, items that have remained a steady presence in Catholic life, with some modest changes, up to the present day. Not only do the exhibit’s main rooms bristle with cleric-inspired clothes, but the entire collection on loan from the Vatican, pieces designed mainly with ritual functions in mind, consists of the couture of the ordained, specifically various popes. Hierarchy, and specifically the earthly hierarchy topped by clerics, could hardly be more central.

The exhibit, in other words, is about power as much as it is about beauty. More precisely, it is about the ways beauty inflects power. The question then becomes what kinds of power the exhibit marshals or interrogates and to what ends.

Visual Culture and the Power of Vestments

There may be a clue in U.S. religious history. In recent years I have spent time viewing photographs from the Second World War. There too, priestly clothing featured prominently in the stories the image makers were telling. One of the most common visual motifs of the war featured a robed priest—often with arms aloft in the moment of consecration during the mass—surrounded by military equipment, especially weapons, jeeps, tanks, and ships. There were obvious reasons for a focus on priests as part of the U.S. effort to promote its cause during the war. Priests offered a clear signal of “religiosity,” a crucial part of the narrative that aimed to distinguish the Allies from their supposedly irreligious or anti-religious enemies. Priests lent an aura of moral righteousness to the U.S. cause, offering reassurance both of the justice of the war and the eternal security of those fighting it. Priests also allowed image makers to tell a story of U.S. religious pluralism.

The priests-at-war motif served other ends as well. These results can be discerned in part by reading Catholic responses to the images they saw being produced by the U.S. propaganda machine: they could not get enough. Military and civilian photographers put Catholics at center stage in the war effort, and Catholic image makers—editors of Catholic journals, books, and pamphlets who often drew on the storehouse of images made available by the government—loved what they saw. Based on the commentaries and captioning they developed to accompany the images, Catholic writers were particularly fixated on the intersection of “heavenly” bodies and objects—priests and the things they carried and wore—with military objects. To be sure, Catholics weren’t just imagining these overlaps. Photographers emphasized them as well through the formal decisions of their art. Led in this way, Catholic writers particularly relished these intersections, routinely pointing them out to readers who might not be aware that they were viewing, say, a mass being said atop an altar jury-rigged out of an ammunition box.

War photographers showed U.S. Catholics to themselves in the context of global war. Catholics took those images and leveraged them into stories about the sublime resonance and holy solemnity of their distinctive ways of being religious. The specific materiality of Catholic ritual life was made to absorb, leaven, and sanctify modern means of death and destruction. Catholic objects, and especially Catholic priests, were not irrelevant remnants from a superstitious past, but potent mediators of sanctifying grace in a terrifying world. The war images gave Catholics a way to think their Catholicism in the midst of a destructive and shifting modern context.

A Mirror of the Church: Sex and Spirituality

Heavenly Bodies is likewise a vehicle for showing Catholics to themselves. This time the salient context is not war. The exhibit instead positions Catholic bodies and their special objects amid three volatile cultural touchpoints of signal importance to the church: gender, sex, and spirituality. First, the exhibit takes place amid widespread challenges to inherited rigidities around gender within and around the church. The case for resuscitating women deacons within the church recently gained attention when Pope Francis directed a commission to explore the issue. Non-Roman Catholics, a good portion of whom differentiate themselves from the Roman church mainly through their support for the ordination of women, have stirred up recent waves of scholarly and popular analysis. On questions of sexuality, a recent publication by exhibit consultant and popular author Fr. James Martin, S.J. raised storms within sectors of the church for its call for a caring ministry for and conversation with LGBTQ Catholics. The clerical sexual abuse crisis has not really abated, and continually reopens discussion of the sex lives of priests, with some wondering whether celibacy and the historic silences and repressions of seminary and rectory can be blamed for producing men willing to exploit their power over the vulnerable. Others have seen fit to conflate sexual abuse with homosexuality, thus creating a scapegoat out of gay priests and pushing silence about sexuality deeper into the fabric of the church. More widely, the exhibit takes place after the success of popular media exploring sexual orientation and gender identity, including television shows like Transparent, which dives into the life of a trans woman and her family. The exhibit also rests within the context of heightened awareness about the sexual exploitation of women by men, including accusations against the star of Transparent, Jeffrey Tambor.

“Spirituality” stands as the third dominant context within which “Heavenly Bodies” must be understood. An oft-cited Pew study from 2015 revealed that there are nearly half as many people in the country (9% of the total adult population) who consider themselves former Catholics as those that call themselves Catholic (20% of the total adult population). Another 9% are characterized as “cultural Catholics.” One might look at this positively, and note that 38% (45% if you count those married to Catholics) of adult Americans have been substantively shaped by the Catholic tradition. But interpretations have tended in the other direction, toward handwringing about decreasing affiliation. A rise in the number of people claiming no religious affiliation at all (23%) has aggravated such concerns. Again, the statistics might be misleading since the so-called “nones” definitively have “some” religion in the form of “belief in God” (61%), an affirmation that religion is “very important” to them (13%), and “daily prayer” (20%). But downward trends in these numbers since 2007, and high rates of disaffiliation among Millennials (in comparison with other generations at the same age), have heightened a popular sense that spirituality is supplanting religion. Indeed, if my classrooms at a Catholic university are any indication, the idea of being “spiritual but not religious” has had tremendous staying power. This notion permeates the exhibit (and the history of modern museums) as well. At the press tour before the official opening of the exhibit, the curator, Andrew Bolton, remarked that most of the featured designers were themselves Catholic, although not necessarily actively practicing. Bolton also remembered his own Catholic upbringing, but made no comments about his current relation to the tradition.

It is in these contexts—heightened scrutiny of rigid norms of sex and gender as well as the increasing feeling that religion is faltering before “spirituality”—that the exhibit reveals Catholics to themselves. What they will see, particularly the implicit pairing of official and imagined clerical clothing, has the effect of a kind of funhouse mirror which rather than distorting reality, brings latent or suppressed elements to the fore.

Showcasing a Countercultural Tradition

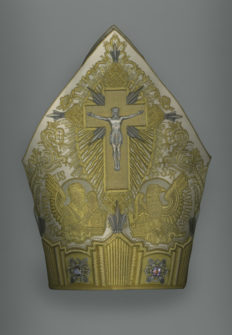

In this case, Catholics are being shown subversive sides of the tradition vis-à-vis U.S. masculinity, femininity, and idealizations of spiritual autonomy. In simpler terms, Catholics will see the ways the church is gender fluid, sexually playful, and resolutely hierarchical. Unlike many in the church, the designers do not shy away, but embrace and even make a virtue of the abiding anti-Catholic barb about a feminized priesthood. This observation, dating back probably to the beginning of the priesthood itself, has long entertained and riled the church’s critics (from inside and out) who see clerical men—celibate and yet with special access to both men and women’s deepest secrets—as disruptive to gender norms. Martin Luther was famous for reviling the non-procreative priesthood as contrary to nature and God’s law. Other critics of the priesthood have seized particularly on priests’ clothing, especially the long cassock and liturgical chasuble, to suggest that a fundamental perversion of standard sexual norms is woven into the church’s hierarchy (see Gary Wills’ Why Priesthood? A Failed Tradition, 25-27). The designers play with these kinds of gendered expectations, borrowing from priestly cassocks worn in the tradition only by men, for example, to dress a manikin with an Ava Gardner shape. A white and gold get-up topped by a tall mitre—the kind that would only be worn by a pope—rests on a form with an impossibly girdled waist and rounded bosom (Rihanna reinforced the look at the Met Gala). The prominent militant Catholic in the exhibit is Joan of Arc, a visionary woman famous for wearing men’s clothing in her pursuit of a role in the defense of France during the Hundred Years’ War. Ordained and vowed men, as well as vowed women, have long been told that they give up sex and the procreative family in order to be married to Christ or the church itself. In keeping with this standard, the mystical tradition, of course, routinely takes readers into saints’ erotic encounters with Jesus. In these ways at least, as Mark Jordan and Anthony Petro have also helped us see heterosexuality, gender rigidity, and sexual prudishness are norms that are not actually normative in the church.

Courtesy of the Collection of the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff, Papal Sacristy, Vatican City.

Neither is spiritual autonomy. The tradition, the exhibit reminds us, is resolutely mediated, the opposite of “spiritual” in that it establishes specific and reserved hierarchical pathways through which one unites with God. This interpretation pushes back slightly against the interpretation offered in the exhibit’s curatorial framing. The exhibit’s subtitle, “Fashion and The Catholic Imagination,” borrows from the great sociologist-priest Andrew Greeley, and frames the exhibit as part of the church’s confirmation that God’s grace is available, potentially at least, through everything in creation. This spiritual reading of Catholicism is certainly woven into the tradition. But the centrality of Holy Communion and Confession as means of grace offers a competing notion. In ordinary circumstances these sacraments are required, and themselves require priests. Surrounded by clerical clothes and prominent talk of hierarchy, visitors to the exhibit encounter a profoundly mediated tradition, not a tradition of independent searching, God in all things, and spiritual autonomy.

They see, in other words, another strikingly countercultural feature of the Roman Catholic tradition. While corporate boardrooms and political offices make gestures toward gender inclusivity, the Roman Catholic priesthood resolutely denies it. And even though the theology of priests has moved fitfully toward collaborative, inclusive, and horizontal models over the last one hundred years, the fact remains, in the words of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), that priests’ ordination still impresses upon them a “sacred power” to “teach and rule” in a mode that is different from lay Catholics’ authority “in essence and not only in degree.” And this is still the way Catholics tend to experience priests; for better or worse, they add solemnity and sacred presence to any situation, they are not like “us.” This elevation, of course, is deeply resented, easily ridiculed, and readily abused. But it is also, as the wartime photos aver, deeply desired.

This desire for religious hierarchy, the fascination with and even need for divine intermediaries who stand apart from everyday people, is one of the most revealing lessons of the Heavenly Bodies exhibit. The Gala, where elite invitees walk the red carpet in front of the museum while sporting exhibit-inspired clothing of their own, is thus not at all out of step with the religious nature of the exhibit, but profoundly in keeping with it: they are not unlike priests in their elevation, their supposed transcendence of everyday life, their access to power, and their constant proximity to our adulation, derisions, and rejection. The fashions show Catholic (and Catholic-adjacent) people the abiding resonance of the idea of priesthood.

In all of these revelations, the exhibit is restrained and relatively modest. There was even more room for play with the undersides of Catholic life had the curators wished to explore them. It is reasonable to assume that cooperation with the Vatican and the support of the Archdiocese of New York helped keep radically excessive themes in check. But this restraint has not stopped some interpreters from criticizing the exhibit as either unseemly in its embrace of church luxury or sacrilegious in its playful appropriations of sacred realities. What these critiques miss, and what I myself missed in my initial reactions to the exhibit, are the ways in which the collection offers Catholics a chance to think about their tradition, to see themselves anew, in a contemporary context of spiritual, sexual, and gender fluidity.