It is my considered view that Pope Francis’s third encyclical letter, Fratelli Tutti (which means we are all brothers), undoubtedly marks a big step forward in promoting interreligious dialogue and peacebuilding, especially between Catholics and Muslims. Moreover, Fratelli Tutti resonates well with the teachings of Islam.

In this regard, it is instructive to note that Pope Francis acknowledges that the subtitle of Fratelli Tutti, “on fraternity and social friendship,” was inspired in part by his February 4, 2019 meeting in Abu Dhabi with Shaykh Dr. Ahmad al-Tayyeb, Grand Imam of the Al-Azhar Islamic University. At this interfaith meeting in 2019, the two renowned religious leaders co-signed the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. Furthermore, Pope Francis chose a Muslim, Judge Mohamed Mahmoud Abdel Salam, the secretary-general of “The Higher Committee on Human Fraternity,” as one of the speakers to formally launch Fratelli Tutti at the Vatican on October 4, 2020. This gesture was unprecedented and was a clear indication of Pope Francis’s intent in the encyclical of pursuing interfaith peacebuilding. In his remarks at the unveiling ceremony, Judge Abdel Salam welcomed Fratelli Tutti as an extension of the Document on Human Fraternity and said the following:

As a young Muslim scholar of Shari’a, Islam and its sciences, I find myself—with much love and enthusiasm—in agreement with the pope, and I share every word he has written in the encyclical.

Judge Abdel Salam’s comments were generous and reflective of the deep resonances of the substance and spirit of Fratelli Tutti with the broader teachings of Islam. In particular, Pope Francis provides us with profound definitions of peace and charity that resonate with Islam. For example, he offers the following broader and comprehensive interpretation of the meaning of charity which echoes fully with the purpose of Zakah, the third pillar of Islam:

It is an act of charity to assist someone suffering, but it is also an act of charity even if we do not know that person to work to transform and change the social situation that caused the suffering in the first place. (para. 186)

Furthermore, the egalitarian spirit of Fratelli Tutti is usefully encapsulated in a paradigmatic verse from the most primary source of Islamic guidance. The Qur’an proclaims the following:

O Humankind! We have created you of a male and a female, and fashioned you into nations and tribes, so that you may know each other (recognize each other); surely, the most honorable of you with God is the best in conduct. Lo! God is the All-Knower, Aware of all things. (Q. 49:13)

The above Qur’anic verse is emblematic of the Islamic tradition’s celebration of human diversity, its embrace of plurality, and its call to get to know each other through intimate knowledge and fraternal relations. One might consider it, as one commentator has suggested, as a Fratelli Tutti Qur’anic verse.

While there is much in Fratelli Tutti which resonates with the traditional teachings of Islam, there are also some aspects of the encyclical which challenge mainstream and dominant understandings of Islam. Here I would like to identify only two such dissonances which may make for useful subjects of dialogical engagement between Catholics and Muslims in the future.

The first contestation is that Fratelli Tutti comes close to rejecting the traditional parameters of “Just War Theory” as morally indefensible given the destructive and indiscriminate nature of modern day weapons of mass destruction. Pope Francis proclaims that:

We can no longer think of war as a solution, because its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefits. In view of this, it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a ‘just war.’ Never again war! (para. 258)

Fratelli Tutti’s skeptical stance on contemporary war ethics is already creating a renewed debate among just war theorists within the Catholic Church. Within Muslim circles, Fratelli Tutti’s challenge to craft a new fiqh al-jihad that takes into account the destructive and indiscriminate nature of contemporary weapons of warfare is even more controversial. There are only a handful of Muslim scholars who have proposed an Islamic theology of nonviolence, such as Maulana Wahiduddin Khan of India, Shaykh Jawdat Sa`id of Syria, and Chaiwat Satha-Anand from Thailand. [1]

Not surprisingly, the innovative viewpoints of these Muslim peace scholars have not been engaged with seriously by mainstream Islamic scholars. This is because of the hegemony of the classical Muslim jurisprudence of jihad which was forged by the early Muslim jurists in response to the imperial politics of the Abbasid caliphate and the Byzantine Empire. This led Professor Sohail H. Hashmi, a leading Muslim ethicist on Islamic war and peace, for example, to assert that an Islamic theology of nonviolence was an impossibility (194).

In light of Fratelli Tutti’s challenge to conventional “Just War Theory” and classical Islamic jurisprudence concerning jihad it might be useful to convene a robust and sustained interreligious dialogue on the ethics of war and peace that takes into account the effects of contemporary weapons of warfare.

A second area of contention with that of dominant interpretations of Islam is Fratelli Tutti’s invitation to religious leaders and institutions to speak truth to power. Here Pope Francis asserts,

Today, in many countries, hyperbole, extremism and polarization have become political tools. Employing a strategy of ridicule, suspicion and relentless criticism, in a variety of ways one denies the right of others to exist or to have an opinion. Their share of the truth and their values are rejected and, as a result, the life of society is impoverished and subjected to the hubris of the powerful. (para. 15)

Most commentators believe that this section of Fratelli Tutti refers to right-wing populist regimes. It is palpable, however, that the reference is much broader and includes all nation states. This is evident when Pope Francis rhetorically asks,

Nowadays, what do certain words like democracy, freedom, justice or unity really mean? They have been bent and shaped to serve as tools for domination, as meaningless tags that can be used to justify any action. (para. 14)

In many countries across the world the idea of religious leaders and institutions challenging the excesses of state power is anathema and frowned upon. This is the case in Western democracies such as France and the United States of America. In the Middle East, this is an even bigger problem. Here religious leaders and institutions have been rendered state apparatchiks whose primary role is to buttress and provide religious legitimacy to state power. In almost all Middle East countries the highest Islamic religious authorities are state appointed, including the Grand Shaykh of Al-Azhar Islamic University, and most Friday mosque sermons are state sanctioned. Moreover, religious leaders who criticize state policies are routinely incarcerated.

There is wide scale agreement among scholars and policy experts that one of the major factors impeding sustainable peace in the Middle East is the despotic and autocratic system of government with which most countries in the region are burdened. It is not difficult to imagine how Pope Francis’s Muslim interlocutors, like Shaykh Ahmad al-Tayyeb, and state-sponsored interreligious bodies, such as “The Higher Committee of Human Fraternity,” will respond to interreligious solidarity action campaigns against human rights violations by Middle East governments. (In 2019 shortly before his visit to the UAE, Human Rights Watch wrote a personal letter to Pope Francis outlining human rights abuses committed by the UAE and requested him to raise the issue during his papal visit.)

It is my considered view that the best strategy religious peacebuilders can adopt in advancing sustainable peace in the Middle East is to render their struggles for religious freedom and tolerance as an intersectional struggle for social justice that links religious freedom to the quest for comprehensive human rights and dignity for all. However, in order to ensure that such an intersectional social justice and interreligious peacebuilding program of action procures positive and sustainable peace in the Middle East, it is critical that it should be initiated, sponsored, and led by local actors and institutions.

It is clear that state-sponsored interreligious dialogue programs will not advance a justpeace for the Middle East. Moreover, such top down escapades invariably involve established and high-profile religious leaders and institutions whose agendas of legitimating status quo power hegemonies often dovetail conveniently with that of state actors. Genuine interreligious peacebuilding programs demand independent religious leaders and institutions who truthfully represent the agony and suffering of their congregations and communities and courageously speak truth to power. Moreover, the agenda for such interreligious dialogue forums should not be restricted to the lack of religious freedom and full citizenship for Christian minorities in the Middle East. While this is an important and essential part of the struggle for peace in the Middle East, the struggle for a justpeace must also address other contentious social justice issues, especially that of the tyranny of despotic and monarchical oppressive systems of government, and the complicity of United States of America in providing uncritical support to these regimes and the unjust apartheid policies of the State of Israel.

Notwithstanding the two issues of contention I have raised above and other differences between Fratelli Tutti and traditional Muslim ethics of war, peace, and governance, the encyclical resonates deeply with the broader teachings of Islam. This includes the deeper meanings of charity, compassion, care for the environment, and of peace and fraternity amongst people of all faiths.

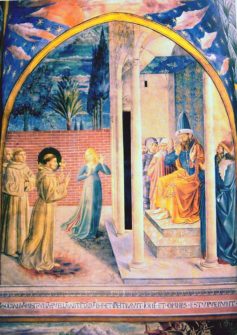

In conclusion, it is my view that through Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis has inaugurated a constructive platform for credible Muslim leaders to enter into a renewed dialogue with Catholics on the critical question of the roots of violence and the building of a justpeace in our contemporary world. Moreover, by locating such a conversation within the broader framework of Pope Francis’s theology of compassion for the poor—which offers a powerful social critique of our global culture of consumerism, covetousness, and opulence—interreligious dialogue will find even greater resonance among Muslims. It is my sincere hope that more Muslim scholars will take up the dialogical challenge presented in Fratelli Tutti in a comparable spirit of reverence and hospitality with which the twelfth century Muslim leader, Sultan al-Kamil, welcomed Saint Francis, from whom the current pope takes his name.

[1] For further reading on Islam and Nonviolence, see Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Nonviolence and Peacebuilding in Islam: Theory and Practice.

This is an excellent bridging of the gap between current Christian and Islamic viewpoints at some depth, with well presented points of difference. May these points become inspirations to take the conversation even deeper and help birth a truly Inter-spiritual perspective.

I’d like to point out that Just War theory was one of the 3 main contributions to the creation of “Christendom” (Christianised Empire) of North African theologian St Augustine of Hippo (354-430). The other two were “Original Sin” and “Eternal Damnation” and Augustine was perhaps the most devastatingly influential Christian thinker at the very foundations of Western Civilization.

It is my contention that we radically revise his contributions to our worldview. Take for example my post entitled “Eternal Punishment in Augustine’s The City of God”, https://soundandsilence.wordpress.com/2009/01/13/eternal-punishment-in-augustine%e2%80%99s-the-city-of-god/

Humanity is One. All Created in that PRIMORDIAL State

We should HONOUR one another and despise Obedience another.

Our BELOVED Prophet Mohammed SAW was once sitting with his companions when a Bier passed by. The BLESSED Prophet stood up.

Someone remarked the person was a Jew.

Our Beloved sternly said،” HE ALSO HAD A SOUL” COMPASSION FOR HUMANITY.

Error rectified.

Should Read Not Despise one another