An Arabic version of this piece is available here.

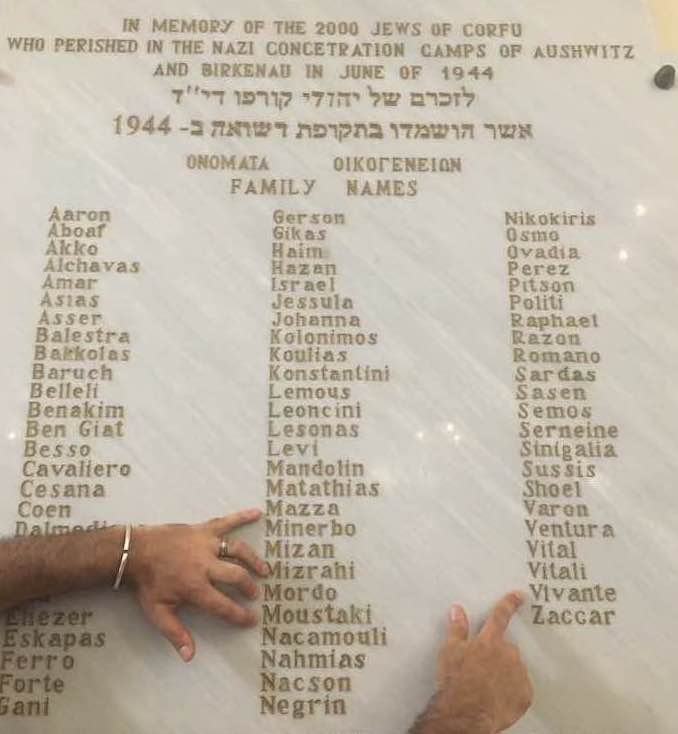

I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive). Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the letter sent by England’s Secretary of State for Education, Gavin Williamson, to all university vice chancellors. Utilizing an authoritarian tone devoid of understatement, Williamson demanded that all universities in England adopt formally what is called “the working definition of antisemitism” drafted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).

Born in 1976, Williamson has been a Tory politician for 25 years. He and his party have not been noteworthy for their passionate activism against racism, antisemitism included. Nor did Williamson find it problematic to serve under Boris Johnson, author of Seventy-Two Virgins (HarperCollins, 2004), a novel that disappointingly recycled antisemitic tropes and stereotypical portrayals of Jews and other British minority ethnic groups.

The letter Williamson authored is littered with antisemitic tropes. A non-Jew himself, Williamson first chooses to single out Jews from non-Jews and, in so doing, officially mark Jews as “other.” Embracing the “divide and conquer” colonial approach, he proceeds to divorce antisemitic racism from similar manifestations of racism with which he is less concerned, including Islamophobia, Afrophobia/anti-Black racism, misogyny, anti-Roma/Gypsy racism, homophobia, and xenophobia vis-à-vis Asians and Arabs.

Most disturbingly, Williamson’s letter upgrades the quintessential stereotype of money and Jews to a new level by linking Jews to monetary penalties and potential state sanctions on universities if their managements exercise what is otherwise a simple academic and democratic right to adopt a view and definition of antisemitism that differ from his. The irony of setting Christmas as the deadline for his pseudo-philosemitic mobilization has apparently escaped Williamson altogether.

The IHRA definition that Williamson labors to impose unilaterally defines antisemitism as “a perception that may be expressed as hatred.” This reading is vague, restrictive, minimalist, and—in the main—emotionalist. It bypasses manifestations of antisemitism that are equally, and possibly even more, important than “perception,” including oppression, discrimination, exclusion, prejudice, bigotry or other tangible actions. Moreover, a wall-to-wall agreement prevails among the rainbow of scholars of antisemitism that one singular definition of the abhorrent phenomenon does not exist. That is the case precisely as there is no one and only definition for racism, feminism, islamophobia, Judaism, Zionism, Islamism, English nationalism, communitarianism, and forms of bigotry.

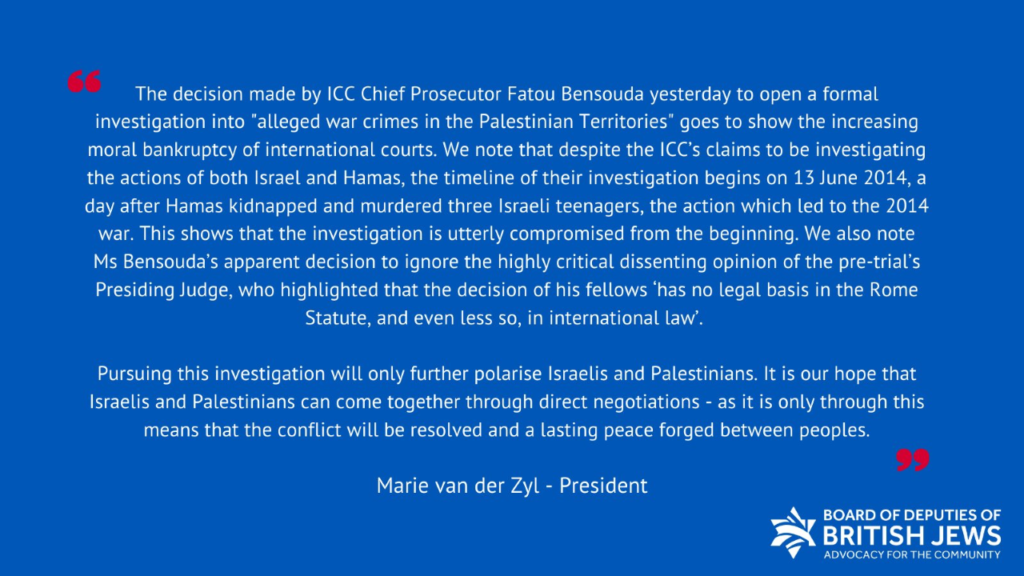

There are at least four additional definitions of antisemitism that can guide the work of scholars or activists and that are analytically superior to that of the IHRA: the definition of the Canadian Independent Jewish Voices; that of the British Board of Deputies and the Community Security Trust; and that of the British Jewish Voice for Labour. However, the most scholarly rigorous definition is “The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism” (JDA) that was made public today (disclosure: some serious reservations notwithstanding, I’m one of its 200 academic signatories). To be sure, Williamson’s top-down state decree of a single definition upon academia—let alone one deemed deficient by hundreds of scholars—runs the risk of echoing Soviet Stalinism and American McCarthyism.

There are at least four additional definitions of antisemitism that can guide the work of scholars or activists and that are analytically superior to that of the IHRA: the definition of the Canadian Independent Jewish Voices; that of the British Board of Deputies and the Community Security Trust; and that of the British Jewish Voice for Labour. However, the most scholarly rigorous definition is “The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism” (JDA) that was made public today (disclosure: some serious reservations notwithstanding, I’m one of its 200 academic signatories). To be sure, Williamson’s top-down state decree of a single definition upon academia—let alone one deemed deficient by hundreds of scholars—runs the risk of echoing Soviet Stalinism and American McCarthyism.

And Then There Is Israel

As many as seven of the eleven illustrations that the IHRA definition marshals to exemplify antisemitism relate to post-1948 Israel (of which I happen to be a citizen). The Zionist/Arab matrix dominates the definition and as a result it often comes across as concerned more with the protection of Israel than the protection of Jews, let alone non-Israeli Jews. As early as 2016 the British Government’s own “Home Affairs Committee” found the IHRA’s definition wanting; cross-party committee members insisted on formally affixing two stipulations:

(1) “It is not anti-Semitic to criticise the Government of Israel, without additional evidence to suggest anti-Semitic intent” and (2) “It is not anti-Semitic to hold the Israeli Government to the same standards as other liberal democracies, or to take a particular interest in the Israeli Government’s policies or actions, without additional evidence to suggest anti-Semitic intent” (italics added).

While it is unclear how precisely such “intent” is to be established or proven—let alone by what body or individual/s—it is clear that Williamson opted consciously to exclude these two surgical qualifications. That seems an additional testament to his instrumentalization of antisemitism for sectarian conservative ends. The Governing Bodies and Presidents/Vice Chancellors of at least 48 universities were unable to withstand the ongoing governmental pressure and effectively all endorsed the IHRA definition top-down without staff consultation. For example, my university’s management endorsed the definition with the Home Affairs Committee’s stipulations; Cambridge and Oxford did the same. While this too remains unsatisfactory, it is somewhat less misguided than adopting the IHRA definition as is.

The definition Williamson insists on imposing carelessly conflates “Jews” with “the state of Israel” and “Judaism” with “modern political Zionism.” The original conflation between these identities and phenomena was—and remains—an inherent organizing pillar of Zionist ideology. Self-proclaimed pro-Israel bodies and individuals exercise this conflation regularly in texts, actions, and advocacy. It comes as no surprise that this conflation has often been reproduced by Israel’s anti-Zionist critics, at times consciously and at other times as a consequence of inexcusable ignorance.

The symbiosis between these opposing, yet mutually-empowering, Zionist/anti-Zionist tides yields the most toxic ground for unambiguous manifestations of antisemitism. This is in contrast to cases where straightforward criticisms of Israel—including by such organizations as Amnesty International, Oxfam, Human Rights Watch, and the Open Society Institute (established in 1993 by George Soros)—have been fancifully labelled as “antisemitic” to delegitimize pro-democratic activism on behalf of Palestinian human and political rights. Three facts that the IHRA definition fails to acknowledge should neither be forgotten nor blurred conceptually: that many Jews are not Zionist; that the majority of Zionists worldwide are not Jewish (including Christian fundamentalists); and that over 20% of Israeli citizens are not Jewish.

Beneficiary of a Double Standard

The IHRA definition which Williamson aims to institutionalize claims that it is antisemitic to apply “double standards to Israel by requiring of it a behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.” Viewed dispassionately through a scholarly lens, this formulation echoes what logicians term “the straw man fallacy.”

First, the overwhelming majority of Israel’s critics worldwide focus on its post-1967 occupation of the West Bank and the actions it is continuing to implement there to date. No democracy in the twenty first century holds a disenfranchised civilian population under such brutal occupation while deepening ceaselessly its colonization, implantation of armed civilian settlers, and illegal settlement construction, all based on religious affiliation and differentiation.

Branding as “antisemitic” criticism of Israeli actions pertaining to its occupation—on the ground that this applies a double standard—is Orwellian. The majority of Israel’s critics demand that Israel cease being the beneficiary of a double standard that has exempted it, for over 50 years now, from democratic requirements otherwise applied to, and expected of, all other democracies. The thrust driving this critique is that Israel will act, and be adjudged, in the same way as standard democracies. If that were to happen, this would remove Israeli exceptionalism, not create it.

Yet a transition of this sort remains absent. This partially explains why leading (Israeli) social scientists define Israel as a diminished form of ethnic democracy, that is, a state that does not meet the minimal requirements that would permit students of Comparative Politics to define it as a “liberal democracy.” For another (Israeli) school of scholars, the label “democracy” should be avoided altogether for the simple reason that the glove does not fit; they thus define Israel as an ethnocracy. For yet a third school of thought, Israel lamentably meets the definition of an apartheid state. Two months ago, the single most prestigious and scholarly of all Israel’s Human Rights Organizations, B’Tselem, published a report titled “A regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea: This is apartheid.”

The above constitutes a standard scholarly debate that lacks any inherent link to antisemitism. It therefore should not be interfered with by career politicians for the purpose of policing speech, as already seems to happen. In fact, the principal author of the IHRA definition, Professor Kenneth Stern, explained on many occasions that the definition “was not drafted, and was never intended, as a tool to target or chill speech on a college campus” and that he himself “highlighted this misuse, and the damage it could do.” It is clear that Williamson did not bother to consult Stern or his writings upon issuing his letter.

Israel vs Civic-Liberal Democracies

The IHRA definition Williamson enforces provides assistance to no one when it resolves that “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” is a form of antisemitism. While such denial can surely assume an antisemitic form, in the majority of cases it assumes instead a straightforward democratic critique. For starters, scholars and non-scholars alike must have the democratic right to question Israel’s democratic credentials and self-defined national configuration, as well as those of any other state.

Israel rests legally upon the notion that all British Jews, for example—including those who have never set foot outside Britain—enjoy more individual and collective rights between the Jordan Valley and the Mediterranean Sea than non-Jewish Palestinians who live in this territory, including those who have never set foot outside of it. That is the case not only vis-à-vis stateless Palestinians in the West Bank (annexed de facto but not de jure by Israel) but also with regards to Palestinian citizens of Israel, who comprise 21% of its population. Demands to correct this state of Israeli legal-political affairs are calls to democratize Israel; they are by no means a form of antisemitism.

Another problem with the IHRA’s uncritical adoption of Israel’s self-indulged “democratic nation” credentials can be illustrated by the fact that both Israeli Jews and non-Jews enjoy equal legal recourse to migrate to Britain and the US and acquire their citizenship. Yet the same democratic feature is nowhere to be found reciprocally in the case of Israel.

An Israeli Jew who marries a non-Israeli Jew from, say, Alaska, enjoys automatically a legal right to naturalize their spouse in Israel; conversely, a non-Jewish citizen of Israel who marries a non-Jew from Ramallah (or Alaska) does not enjoy the same equal right to bring their spouse and naturalize her or him. That also means that British or American non-Jews—including Palestinian American Christians, Muslims, seculars, and others—have no viable legal pathway to emigrate to Israel, nor to reunite with their indigenous families there, nor to become citizens in Israel. Yet British or American Jews automatically have this right whether they like it or not.

Israel is thus neither a democracy in the ways that Britain or other liberal democracies are, nor does it embody a national configuration that can, or should, remain above interrogation. Non-Jews in general, and Palestinians in particular, who seek to have rights in Israel equal to those bestowed upon Jews would first need to undergo a successful religious conversion to Judaism.

As is the case in other democracies, British immigration laws do not restrict apriori possible migration to Britain on the basis of religious affiliation alone. It is not too hard to imagine what the response of British democrats (Jews among them) would be if the right to migrate to Britain was reserved to non-Jews alone. Another example is that the combined state of legal, national, and political affairs in Israel easily enables non-Israeli Jews to purchase land in Israel even if they are not citizens. For Israeli citizens who are not Jewish this is effectively impossible to do. The Israeli notion of ascribing different rights to different religious groups—of both nationals and non-nationals—is absent in liberal democracies because it fatally corrodes the defining notions of civic democracy.

It therefore should come as no surprise that for its non-Jewish citizens, Israel is experienced as a Jewish and undemocratic state. Many Jews with democratic convictions subscribe to this view with ease. The attempt by many—chief among them Israeli Jewish and non-Jewish citizens for whom democracy is sacrosanct—to remove such discriminatory and unequal conditions and legislation, and, in doing so, to democratize Israel by bringing it nearer the model of a state that is for all its citizens (as Britain and the US are for example) does not constitute antisemitism.

The IHRA’s stipulation that “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” is a form of antisemitism is thus deceptive. It is on standard democratic grounds—not on antisemitic grounds—that many oppose the sweeping extra-territorial privilege of non-Israeli Jews to exercise a “national right to self-determination” inside Israel/Palestine that is bestowed upon them at the direct and inevitable expense of the individual and collective rights of non-Jews living in Israel/Palestine.

Let us lastly think of a European or non-European individual who denies “the right to self-determination” to the people of Catalonia, the Basque country, Scotland, Québec, Corsica (or others worldwide). Does this make them by definition racists vis-à-vis the Scots, Catalans, Québécois?

This is a wonderfully clear essay! Thank you.