Is a decolonial approach to the Qur’an possible? And if so, how can such an approach be of benefit to scholars of Islamic and religious studies? In the last few decades, various disciplines in the humanities have witnessed an unprecedented growth in both self-criticism and creative reconstruction. This growth is commensurate with the increased presence of racial and religious minorities in the academy and the subsequent epistemological interventions they have brought. Thanks in large part to the pioneering work of scholars like Edward Said; Gayatri Spivak; Talal Asad; Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh; Dipesh Chakrabarty; Sylvia Wynter; and more, the academy has become a fresh site for the interrogation of existing modes of knowledge and fertile soil for the birth of novel ways to think through the task of decoloniality.

This essay follows in the footsteps of such scholarship by providing a short reflection on what a decolonial approach to Islamic studies can potentially offer scholars of the field, starting with the Qur’an—the central scripture of Islam—as a site for decolonial analysis and praxis. However, rather than review or express preference for a hermeneutical or exegetical approach in the literature, I instead reflect over the Qur’an as an epistemological structure and meditate on the task of students and scholars in appreciating it as such. This essay is thus less about marshaling a methodology of Qur’anic hermeneutics or exegesis than it is about approaching the Qur’an—and by extension the wider Islamic tradition—from a structural and epistemological standpoint.

On the whole, much more work needs to be done by scholars in interrogating how they write about “religion,” both within and outside of the field of religious studies. This may have partly to do with the implicit (or explicit) secularity of western academia as a discursive site, or with residual conceptions of religion drawn from the European Enlightenment—whether liberal or Marxist—as a distinct interior/private domain of belief (as opposed to that which is exterior/public) or as mystification concealing material oppression. As An Yountae writes in this publication, “The large absence of engagement with religion in the study of modernity/coloniality is symptomatic of the coloniality of knowledge which informs the religious/secular binary. Taking decolonial thought seriously means considering the challenges and insights decolonial thought offers to the study of religion.”

This absence of decolonial religion is particularly acute in Islamic studies, where paradoxically, in an attempt to distance themselves from traditional Orientalist scholarship, which had historically relied on an essentialized Islam as the sole unit of analysis and/or explanatory factor, scholars in the field have largely avoided considering Islam as it shapes the subjectivities of the Muslim faithful in meaningful ways, let alone drawing from its resources as a mode of decolonial critique. One notable exception is the work of Salman Sayyid and scholars in Critical Muslim Studies, whose works can offer a starting point for discussion on the subject.

As Talal Asad has aptly noted, the terminologies we employ to make sense of “religion” are not universal but rooted in a Protestant Christian history. Thus, a decolonial approach to the Qur’an also means de-Christianizing how we understand it as a text and its relationship to Muslims. It follows that the themes, motifs, narratives, and frameworks of the Qur’an ought to be understood without having the need to ground themselves first in Christian and Christianizing versions of the same.

The Structure of the Qur’an as a Decolonial Site

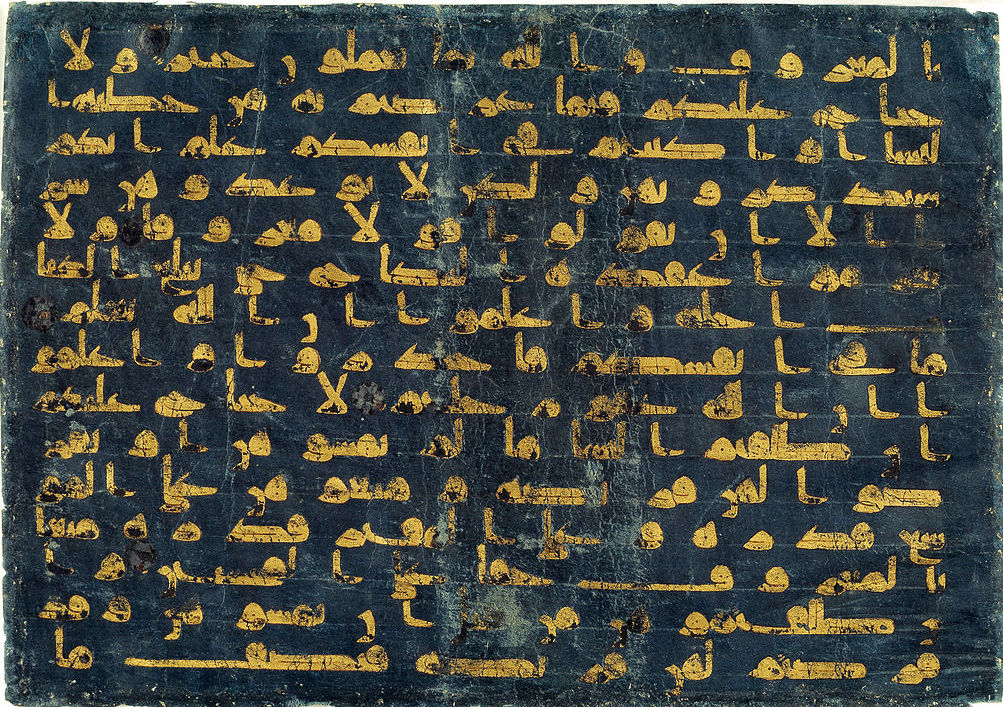

The Qur’an is not an easy text for those unfamiliar with its structure. If one is reading it in translation with an eye accustomed to a linear-chronological reading of scripture, it poses a challenge. As Muhammad Abdel Haleem writes, its content “was placed in different sections, not in chronological order of revelation, but according to how they were to be read by the Prophet and believers” (xvi–xvii). The original Arabic reading/recitation is thus central to Qur’anic self-disclosure.

Furthermore, the Qur’an’s stories are framed not as distant tales of the ancients, but as memories to be retrieved: “And remember when We took a covenant from the prophets, as well as from you (Muhammad), and from Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, son of Mary. We did take a solemn covenant from all of them” (Q 33:7). The distance between the reader and the event is collapsed, as if to suggest that the reader was there. Memory is not a thing of historical time, but a metahistorical device that serves to invigorate the present. In every moment, through the pain and the joy, we were with Muhammad, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.

In the rest of this essay, I would like to reflect on three points. First, on the ordering of the Qur’an’s verses; second, on the centrality of the original Arabic recitation to Qur’anic self-disclosure; and third, on the Qur’an’s employment of memories as epistemology, as I believe all three can offer potential avenues for decolonial scholarship.

Qur’anic Organization as Decolonial Subversion

If one were to read the Qur’an in translation, the sudden shift from one story, theme, or concept to another with no indication may strike one as odd, but it is precisely this lack of linearity that makes the Qur’anic corpus a subversive site for thinking about the decolonial. While we moderns may expect—or even demand—a text to have a sense of linearity so that it can be comfortably compartmentalized, the Qur’an structurally defies such terms from the very beginning. It consciously refuses compartmentalization, demanding to be taken holistically on its own terms. The organization of the Qur’an is itself a form of liberation.

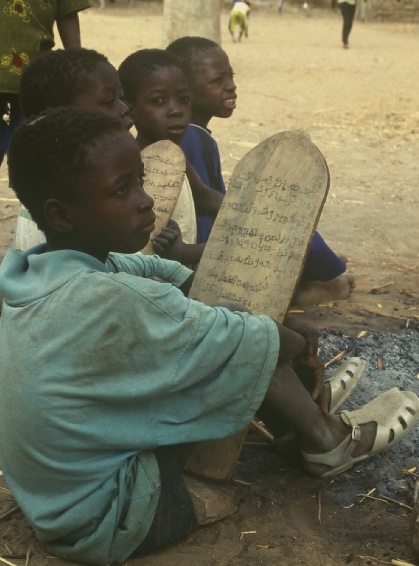

The recital of these stories, passed down orally from generation to generation, engages the sensory, cognitive, and bodily senses all at once. They are inseparable, and to view one to the exclusion of others would constitute an act of epistemic violence. It is because of this quality of orality that the Qur’an is memorized by millions of Muslims of all social classes throughout the world, typically starting from a young age. Indeed, both secular and religious scholars alike have marveled at how its prosaic exhortations flow with its poetic virtuosity. One may not know a single word of Arabic and yet listen to a recitation feeling the continuity between its rhythmic verses as if they were exactly where they were meant to be. This is where the text begins to make more sense, for without the embodied recitation of the Arabic verses, engagement with the text can feel frustrating or wanting. One may, however, ask whether it is possible to thus appreciate the Qur’anic text in a language other than the original. Does decolonization necessitate a type of linguistic supremacy or nativism?

Qur’anic Pedagogy as Decolonial Embodiment

In his book Secular Translations, Asad clarifies that it is not the Arabic language per se that is sacred and nontranslatable, but “the enunciation of divine virtues” within the Qur’an “whose full sense is not given in a dictionary” and requires cultivation (60). This cultivation is nurtured not merely through reading the text, but living it, through recitation and other forms of embodiment.

Here, the work of Rudolph T. Ware III is an instructive example: “We have been missing a basic fact: the human being as a material reality and practices of corporeal remolding are essential for the classical epistemology of Islam to work” (7). Ware’s intervention stands at the forefront of decolonial religion, even if he may not explicitly express it as such. By tracing the history of Qur’an schooling in West Africa, Ware shows how modern (secular) academia and modern knowledge as a whole, with its Cartesian split between mind and body, fail to appreciate—let alone understand—premodern Islamic modes of learning in West Africa.

Furthermore, it is key to see the Qur’an in relationship to the discursive tradition that flows from it. As Asad writes, “the nontranslatability of the Qur’an in a liturgical context makes it difficult for political as well as ecclesiastical authority to control Qur’anic meaning. The original is always present, generating unlimited possibilities of meaning” (60–61). It is precisely the Qur’an’s untranslatability that makes it a generative site for decolonial praxis. The epistemic humility it engenders is a refusal to submit to colonial modernity’s attempts to domesticate the text.

Scholars of Islamic studies might benefit from conceptualizing the Qur’an, and by extension the Islamic tradition writ-large, as sites for the cultivation of subjectivities that can only be formed through terms of their own making, rather than as problems to be solved within or against colonial modernity’s paradigmatic modes of being. By rethinking the terms along these lines, Islamic studies would better be able to cross-fertilize with Black studies, Africana studies, Latin American studies, feminist studies, and more.

Qur’anic Memories as Decolonial Struggle

As Ware powerfully expresses with reference to enslaved West African Muslims forcibly brought over to the Americas, they were “stripped naked, beaten, and starved in the hold of a slave ship, shipped thousands of miles from home, and put to a lifetime of labor in unfamiliar surroundings,” but nonetheless endured all of the above “without surrendering [their] knowledge” (69). They never surrendered their knowledge because they never surrendered who they were, as the knowledge—the Qur’an—was embedded into their being.

Just like in the Qur’an’s call to remember the prophets, in Black radical thought, invoking the ancestors is not merely a rhetorical technique, but an epistemological grounding. It was in reading about others, James Baldwin once said, “that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.” The temporal distance between “ancestors” and “descendants” is severed by the transcendental immediacy of the present. There is no “drawing from the past” because there is no “past” in the sense of linear historical time.

“Remember,” as the Qur’an says. The prophets and ancestors are with us now.

The intent of this peice is to argue for a de-colonial view of the meaning of the “Qur’an.” But as a scholarly discourse – that ventures into my field – how does this view of “Islam” – an essentialist view, although it engages the discourse of post/decolonialism – contest the putative “colonial” view of Islam? or better – why does it not seek to acknowledge the unavoidable contamination of the many iterations of Islam by the unavoidable “colonial” influences with which it developed? The story of contamination and cross-polination is perhaps more consistent with critical approaches to the study of “religion” . I am a bit confused by this, as its aim – to ask for a more thorough “de-colonial” approach to Islam and respect for critical “post-colonial” Islamic studies – shoots itself in the foot by suggesting an un-interrogated metaphysical preciousness for the Qur’an: “The epistemic humility it engenders is a refusal to submit to colonial modernity’s attempts to domesticate the text.” Such a claim demands a critical framework; such a claim demands my respect in the context of one human to another; but as a claim from a contemporary scholar of “religion,” it begs the question – what epistemic humility” Please contextualize – are you speaking from a critical theory perspective, or from a de-colonial/post-colonial emic perspective? Much worthy observation here, but needs theoretical coherence.

“Much worthy observation here, but needs theoretical coherence.”

You mean:

Much worthy observation here but needs to be colonized…

Love reading it.

Probably I need to read few time to fully appreciate. Thanks