A USA Today interactive report on President Trump’s border wall—proposed during his 2016 presidential run—opens with the lines: “On a map, the southwestern Arizona desert is an empty stretch, the size of Connecticut, a sea of nothing. On a map of deaths, it is a sea of red.” The land, according to the author, is “harsh.” Migrants who travel across land known as the Devil’s Highway are dying in large numbers—unidentified remains are stored in coolers in government buildings, buried in mass, anonymous graves. The vocabulary of death is pervasive in discussions of the southern borderlands and transnational migration. Indeed, Border Patrol reports that more than 8,000 migrants have been killed attempting the crossing since 1994, when the United States implemented a policy known as Prevention Through Deterrence (PTD). However, according to No More Deaths, the agency notoriously underestimates this number. And it cannot account for the bodies that are never found.

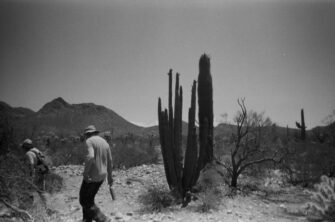

Almost overnight, PTD increased the number of Border Patrol agents and the use of militarized technologies at urban ports of entry, rerouting migration to the Sonoran Desert. This policy has led to an unimaginable loss of life. In the desert, migrants succumb to dehydration, heat stroke, and hypothermia. They slip and fall attempting to climb a gravelly hill; they are bitten by a venomous snake, or they become so physically exhausted that they are unable to continue on their journeys. When this happens, their coyotes (or smugglers) often forge ahead without them. PTD also led to militarized checkpoints at every exit from the Tohono O’odham reservation. These checkpoints were outfitted with high-definition cameras, motion sensor systems, and 360-degree ground-penetrating radars. Todd Miller calls this a “high-tech occupation.” Through PTD, the United States seeks to conscript land to police migration. And, though scholars largely argue that the Sonoran Desert cooperates and collaborates with state agents, my fieldwork has taught me that the opposite is true. Land is sacred—positive and negative, nurturing and overpowering—and, as such, it poses a problem for enforcement and militarization.

Notably, Jason De León has identified the Sonoran Desert as a “killing field, a massive open grave” (8). De León argues that, as a result of PTD, nonhuman actants—objects, minerals, environmental conditions, animals—play a crucial role in border control. In The Land of Open Graves, he writes that a “hybrid collectif”—mountain lions, rattlesnakes, scorpions, hot sand, monsoons, flash floods, deep canyons, and the broiling sun—has been recruited by lawmakers to control and limit human mobility (39). While he concedes that the desert does not act alone, De León nevertheless describes land as a weapon or a death-dealing ecosystem. In short, he argues that the United States government has outsourced border enforcement to the desert itself. But, the desert—a sacred landscape, alive and active in webs of relation—never works in one singular or fixed way. As scholars like Leanne Betasamosake Simpson richly propose, land is active and mobile, though “conquistador-settlers” (to borrow the language of Tiffany Lethabo King) have long imagined land as inert matter, as a set of resources able and willing to be tamed and operationalized. According to Marisol de la Cadena, these are competing ontologies, “more than one and less than many worlds” (108).

Where I disagree with De León, then, is in the way he aligns the desert with the profane, the way he grants victory to the settler state, presuming that land only acts by disappearing and decomposing migrant bodies. The Sonoran Desert is the lushest and most biologically diverse in North America, home of the O’odham—including four federally recognized tribes: The Tohono O’odham Nation, the Gila River Indian Community, the Ak-Chin Indian Community, and the Salt River (Pima Maricopa) Indian Community. It is sacred land, mobile and facilitating mobilities, including pilgrimages, migrations, and rituals. It is unpredictable, uncontrollable, negative and positive—harming and healing, inspiring dread and astonishment. The sacred does not travel in uniform ways, but rather takes contradictory and volatile routes. And while land can prove deadly for migrants who are unaware and unfamiliar with its rhythms, it can also enable fugitive crossings. Border walls, militarized checkpoints, and surveillance technologies do not necessarily collaborate with land against migrants. Rather, they seek to tame the land and its sacred energies. The settler state is not allying itself with the desert. It is actively working to destroy the desert, or—as I argue in my forthcoming book, Sanctuaries Everywhere —to render it spiritless, disenchanted, and profane.

The sacred does not travel in uniform ways, but rather takes contradictory and volatile routes. And while land can prove deadly for migrants who are unaware and unfamiliar with its rhythms, it can also enable fugitive crossings.

The Sonoran Desert has long been cast as negative sacred—a “sea of red,” to return to the USA Today report, an arid land that disappeared settlers, harbored fugitives, and facilitated the unauthorized crossings of Chinese migrants and enslaved people. Negative sacred energies are deadly, unstable, volatile, and easily angered. Joseph Nevins insists that the nation-state has strategically narrated the borderlands as wild and unruly. In Operation Gatekeeper, he writes about Prohibition-era depictions of border districts as sites of sin and promiscuity and about the declaration of the War on Drugs, when border crossings became framed as a national security issue. He shows how the southern border has long been imagined as “out of control” in order to facilitate more surveillance and policing (175). Lisa Marie Cacho further explains that “ideas about spatial violence naturalized colonialism, enslavement, and genocide because it explained why in some regions of the world people were masters of their own (and others’) environments and others were subjugated by other human beings” (73). The Sonoran Desert and its O’odham, or people, have been framed as negative sacred, violent and barbaric, underscoring the need for militarized intervention.

While conducting fieldwork for Sanctuaries Everywhere, I met Dora Rodriguez, who migrated across the Sonoran Desert in the summer of 1980 with a group of twenty-six Salvadorans fleeing a US-backed genocidal government. Thirteen migrants survived and thirteen died during the crossing. She detailed how saguaros resemble humans in the dark—looming, ghostly figures. She explained how dehydration made her dizzy, how some fellow travelers became deranged and homicidal, how others doused their lips in toothpaste to avoid sunburns. Dora called the desert deceptive, a maze that refuses to spit you out. Dora was locked out of good relations with the land, unprepared for what it meant to enter the desert. In fact, the coyote told her group the crossing would take less than a day. Some women even walked across Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in their stilettos.

Both state agents and coyotes seek to master land—to know the desert, tame it, and make it useful to their designs. Land, though, is variable and unpredictable, excessive and abundant. Surveillance infrastructure and militarized enforcement seek to discipline these negative and positive energies, to regulate mobility—the mobility of unauthorized migrants, of other-than-human animals like bobcats and ocelots whose mating patterns are being disrupted by walls and fences, and of the O’odham, whose rituals and kinships traverse the transnational border. Land is too much to be controlled or managed. As Max Liboirion argues, “land is a verb.” They differentiate lowercase land as resource or tool and uppercase Land as a set of relations “between the material aspects some people might think of as landscapes — water, soil, air, plants, stars — and histories, spirits, events, kinships, accountabilities, and other people that aren’t human” (43). This includes rituals like the Tohono O’odham salt pilgrimage that transgress borders, land defenders including Nellie Jo David and Amber Ortega who disrupt enforcement efforts by sheltering sacred land, and migrants and their coyotes who hide in arroyos, rest under mesquite trees, and blend into the night carrying water bottles coated in black nail polish. For the Border Patrol, the desert is not so much an accomplice as it is an obstacle to catching and detaining migrants. Saguaros stand in the way of walls, and so they are cut down. Ancestral burial grounds are desecrated. Mountains harbor fugitives, and so they are blasted to make way for switchback roads. O’odham, too, are an obstacle. They present alternatives to militarization and enforcement.

Both state agents and coyotes seek to master land—to know the desert, tame it, and make it useful to their designs. Land, though, is variable and unpredictable, excessive and abundant.

I close this essay with a scene from my book: While on a humanitarian water drop organized by the Tucson Samaritans, during which volunteers leave food and water along migrant trails, a travel companion shows me an article posted by CNN: “Hundreds of vultures have made a perch out of a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) radio tower, and the government has had enough.” For weeks, the flock of birds coated the structure with feces and vomit, making it nearly impossible for CBP to patrol the border. The two of us burst out in laughter, amazed by how the vultures mock enforcement efforts, how they so effortlessly outwit billions of dollars worth of technology. As we continue along the dirt and gravel road that runs parallel to the wall, I spot a section where the free-flowing Santa Cruz River meets the 30-foot-high steel panels. Undeterred by the towering fence, the water continues to run its course—its constant rush a protest against wall construction. Suddenly, another volunteer draws my attention to a decomposing coyote caught between the steel bars. Unable to fit through the four-inch-wide gaps, the animal likely starved to death. Animals, land, threaten enforcement efforts. They refuse militarization. And so the profane world works to render land lifeless, installing walls and barriers that murder coyotes and deplete natural springs. For the state, the Sonoran Desert is a problem, not a partner.

To return to Liboiron, PTD sees land as a resource, as a weapon to be used against migrants and Indigenous people, as a tool to ensure “settler futures” (17). While it is undeniable that PTD is designed to deter migrants, the Sonoran Desert does not only act as a “killing machine” or a landscape that facilitates death, disappearance, and destruction. It is not only, as Gilberto Rosas writes, a “treacherous geography.” The desert’s sacred energies are an unruly affront to enforcement agents who seek possession or mastery. Land is dizzying, dangerous, excessive, awe-inspiring, and life-threatening all at once. It is sacred and so it is mobile, shapeshifting and refusing to stay in place. This restlessness poses a threat to border enforcement. Land rebels, endlessly.

Suggested reading:

Max Liboiron, Pollution is Colonialism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022).

Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the Illegal Alien and the Making of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (New York: Routledge: 2002).

Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014)

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2017)

Hi Barbara,

I am excited to be on the zoom call with you next week with the BCA. When I read this article, I wondered if you had heard of the Migrant Quilt Project. It was started by Jody Ipsen to memorialize people who died in the Tucson Sector of the Sonoran Desert seeking safety. I was honored to have made the quilt for 2020-2021. I have attached the link to the statement I wrote describing the experience of making that quilt. (https://migrantquiltproject.org/tucson-sector-2020-2021/) From there you can see all of the other quilts. The quilt project is housed in the Arizona History Museum and can travel around the country. Looking forward to hearing you speak next week. Sincerely, Gale Hall