On April 1st, 2022, Pope Francis met with a delegation of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. He publicly apologized, naming “indignation and shame” for the violence and harm done to their peoples, especially in residential schools run by local Catholic parishes and religious orders. This statement came after a long and tenuous struggle within the Canadian Catholic Church and with the Vatican as to how to respond to growing historical awareness of persistent and horrifying abuse of children and the dissolution of families and cultures through the residential school system. “All these things,” lamented Francis, “are contrary to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. For the deplorable conduct of those members of the Catholic Church, I ask for God’s forgiveness, and I want to say to you with all my heart: I am very sorry.”

Joining with the Canadian Catholic bishops, Pope Francis’s pastoral visit and his unequivocal apology is an important step in the reconciliation process. Apologies matter. In the structure and focus of his April 1st, 2022 statement, he navigates the institutional role of the Church and social sin effectively. In doing so, Pope Francis demonstrates that he understands the importance of memory and a good apology more so than his predecessors. Thinking critically about the apology, I want to briefly put it in context, examine what makes for a good apology (and why it often feels like the Catholic church struggles to make a good apology), and look forward to the pope’s upcoming visit to Canada.

Setting the Stage: A Persistent Call for Apology?

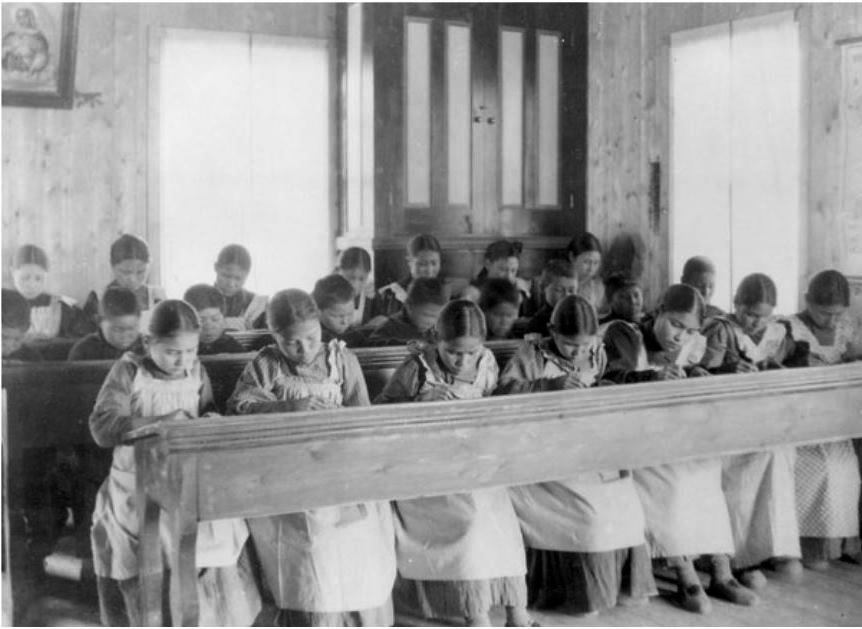

From 1870–1997, more than 150,000 children and young adults went through the Indian residential school system in Canada. This system was part of an official state program, but seventy percent were operated by the Catholic Church or Catholic religious orders. These schools were infamous among Indigenous communities for their intentional suppression of indigenous culture, widespread physical abuse, and neglect. In 2015, the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued a call to action with 94 action items. Item 58 specifically called for an official papal apology delivered in Canada like the one Pope Benedict XVI gave to Irish victims and survivors in 2010.[1] In 2017, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau asked Pope Francis to visit Canada and to publicly apologize for the Catholic Church’s participation in the violence and abuse that characterized the Indigenous Residential School system.

Responsibility for what happened in the Indian residential school system rests with both the Canadian government and the Catholic Church. There have been many apologies both before and after the call to action from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops and individual bishops. Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI both made statements of apology and regret for the unjust treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada (and elsewhere). Yet, calls for a more robust apology from the Vatican and even from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops remained. From the perspective of the Indigenous communities, the previous apologies were not sufficient. Benedict XVI’s expression of “great sorrow,” still fell short of an apology and they continued to call for an apology from Rome in Canada, addressing the entire Canadian Catholic Church, not diocese by diocese, religious order by religious order. Additionally, questions remain about access to documents and participation in the financial settlements. Ultimately, the situation became acute once more in October 2021 with the discovery of one mass grave of 215 children at Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.

A Good Apology: Recognizing more than Sorrow and Complicity

According to a Catholic peacebuilding framework, a good apology is central for creating justice and healing within a community. On John Paul Lederach’s account, “Acknowledgment is decisive in the reconciliation dynamic. It is one thing to know, it is a very different social phenomenon to acknowledge. Acknowledgment through hearing one another’s stories is the first step towards restoration” (26). In Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis echoes this: “we can never move forward without remembering the past, we don’t progress without an honest, unclouded memory” (para. 249).

A good apology is necessary, but it is a practice which the Catholic church as an institution has struggled to carry out. All too often the ecclesial apologies concerning historical violence done to indigenous communities and racialized minorities, or in the case of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, feel inadequate. Most often they express deep sorrow while taking pains to frame transgressions as being carried out by a minority or a few bad individuals who committed a harm. The apologies fall short because they apologize for complicity but not culpability in the horrible violence that has occurred.

All too often the ecclesial apologies concerning historical violence done to indigenous communities and racialized minorities, or in the case of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, feel inadequate.

Complicity acknowledges some involvement, largely centered around an individual failure to stop or correct an injustice. However, while doing so, it lessens the responsibility of those within that larger system which enabled that failure to address injustice. Moral culpability, meanwhile, is about taking actual responsibility for wrongdoing. In common parlance, complicity is passive and culpability is active when it comes to one’s relationship to the harm committed. The good apology must go beyond complicity by recognizing culpability in wrongdoing and harm when one was an active participant. The bad apology, on the other hand, avoids including the speaker in the story either by focusing on their feelings or making the harm about the actions of other outliers.

“We do not usually rush to expose our vulnerability and our sinfulness,” noted Archbishop Desmond Tutu reflecting upon South African’s TRC, “but if the process of forgiveness and healing is to succeed, ultimately acknowledgement by the culprit is indispensable–not completely but nearly so” (270). For the Catholic Church in the Americas, this means a recognition that as an institution we were not just complicit in the oppression of non-European persons in the so-called “New World,” but a powerful participant in shaping, implementing, and reinforcing those systems. This requires a deep and nuanced understanding of social sin and our moral culpability in taking active part in committing harms.

Pope Francis is not the first pope to apologize for the historical injustices committed on behalf of the Church. Pope John Paul II famously did so on several occasions. Catholic social teaching has also long condemned all forms of colonialism and neo-colonialism. The difference here is that Pope Francis more clearly recognized when the Church was implicated in moral harm and identifies with the victims in doing so. This is deeply present when in Bolivia and in his apostolic exhortation Querida Amazonia, he apologized to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, “not only for the offenses of the Church herself, but also for crimes committed against native peoples during the so-called conquest of America.” This is in stark contrast, for example, with the way Pope John Paul II began his 1995 Letter to Women framing the role of the Church in patriarchy and sexism without accepting institutional culpability, “And if objective blame, especially in particular historical contexts, has belonged to not just a few members of the Church, for this I am truly sorry.”

In his recent apology, Francis noted, “it is chilling to think of determined efforts to instill a sense of inferiority, to rob people of their cultural identity, to sever their roots, and to consider personal and social effects that this continues to entail: unresolved traumas that have become intergenerational traumas.” One lingering barrier to healing and reconciliation is the unresolved trauma tied to the Catholic Church’s role as arbiter among Catholic nations during the Age of Discovery. In the last decade, I have been part of two very different Catholic listening sessions with Indigenous leaders in the Americas and in both cases, someone called for the pope to publicly rescind the fifteen century papal bulls tied to the doctrine of discovery. Historically, Inter Coetera (1493) was nullified by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 and by other papal bulls such as Sublimis Deus (1537) which upheld the dignity and property rights of indigenous peoples encountered by Christians.[2] Technically, Church leaders in the United States, Canada, and from the Holy See are all completely correct that any invocation of these papal bulls or the doctrine of discovery by nations and courts bears no connection to the ecclesial. They are not valid for the Catholic church. Nonetheless, at the 2018 Assembly of First Nations members concluded that these existing repudiations were “not enough.” Practically, the papal bulls, the participation in shaping the “Age of Discovery,” and the legacy thereof remains an unresolved trauma for the indigenous of the Americas.

The difference here is that Pope Francis more clearly recognized when the Church was implicated in moral harm and identifies with the victims when apologizing.

The Catholic church, including the current pope, still struggle with the legacy of Catholic missionaries during and after colonization. The last six papacies have sought to put the Catholic church on a path of evangelization that focuses on engagement, inculturation, and the valuing of freedom of religion and peoples. They all spoke critically of earlier periods of missionary cooperation with conquest and colonialism. Yet, for the reasons identified above the apologies have felt insufficient. There is a deep unease about Pope Francis’s decision to canonize Junipero Serra as someone who “sought to defend dignity of the native community” in 2015 over the vocal objections of indigenous communities because of the way in which Serra intentionally sought to eliminate indigenous customs and culture.

Hope for Dialogue and Friendship: Grappling with the Past to Move Forward

Good apologies are merely a step upon which a path of more fruitful dialogue and friendship can be walked. This is another place where the April 1st apology, building on the statements in Bolivia, in Querida Amazonia, and in Laudato Si’, are instructive. Pope Francis’s engagement with Indigenous peoples and traditions seeks to praise insights from their traditions from which non-Indigenous peoples should learn, especially with respect to protecting non-human creation. This also involves giving specific attention—as both the pope and the Canadian bishops have attempted to do—to ongoing injustices that are often ignored, such as exploitation related to extractive industries and the “inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.”

Pope Francis is scheduled to visit Canada on July 24–29, 2022. Papal visits are a unique time of excitement. They energize the local church and have a deep symbolic power unlike much else. Take, for example, Pope Francis’s decision to personally open the Holy Door at Bangui’s Cathedral in anticipation of beginning the year of mercy on November 29th, 2015. Opening the holy door to usher in a year of mercy in the Central African Republic revealed a broader and more inclusive vision of mercy focused on those at the margins. There is much anticipation and anxiety over how Pope Francis will address the legacy of harm done by Catholics and the Church itself to the First Nations peoples of Canada (and to the Native Americans in the United States). The pope himself describes the trip as “a penitential pilgrimage, which I hope, with God’s grace, will contribute to the journey of healing and reconciliation already undertaken.” He understands the importance of a good apology and the deep pastoral recognition that we “have to learn how to cultivate a penitential memory, one that can accept the past” in order to move forward in dialogue and friendship (para. 226).

[1] Item 58 is one of two specifically relating to the Catholic Church. The other, item 48, called upon the Catholic Church and other churches to “publicly adopt and comply” with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples. This is something the Holy See was already a party to at the United Nations, and on which the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops similarly made a public statement of support as part of their responses to the Call to Action.

[2] See Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, “The ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ and Terra Nullus: A Catholic Response. March 16, 2016.

Why doesn’t the Pope revoke the Treaty of Tordeillhas and the underlining Bulls that created this disaster in the first place? As long as these documents prevail, it is virtually impossible to find a just resolution simplly by making an apology. There are many ways to compensate the iNDIGENOUS PEOPLES FOR THEIR SUFFERING despite the challenges that must be addressed in seeking a just resolution. The same problem exists in all of North America, Africa, Australia, South America and countless island nations around theworld. This whole problem begins with the Pope and the treaties and Bulls that remain as the main reference source to justify the reign of conquest by the colonial powers

Perhaps scholarships could be offered to the Indians school.

Such as what was done at Georgetown University discussed in the article on Georgetown University article on a similar situation.

From observations the people of the Indian school are unhappy. Some type of acknowledgement or apology might be mindful.