How can a society that values human dignity simultaneously perpetuate cultural and structural violence? In practice, the dignity and personhood of some are valued over others. The question may be, then, how to apply dignity in a normatively inclusive and egalitarian way.

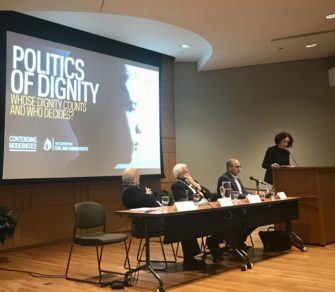

Panelists Atalia Omer, Professor at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, Notre Dame Law School Professor Doug Cassel, Georgetown University Professor Charles Villa-Vicencio, and Kroc Institute Professor Ebrahim Moosa all considered “whose dignity matters” at the “Politics of Dignity” panel on October 9th, 2017. Held at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, the event was co-sponsored by Contending Modernities and the Center for Civil and Human Rights. We invite you to watch the recording below.

“Each human being has intrinsic worth and we all have value, we all have the right to be treated with respect” began Doug Cassel, drawing on the work of Gerald Neuman and Christopher McCrudden. Charles Villa-Vicencio went further: “human dignity means the fundamental transformation of human structures…. A radical commitment to all people across the planet.”

This dignity takes many forms, beyond the “western Christian” sanctification of individual dignity, which has made its way into secular conversations as autonomy, as Ebrahim Moosa noted. Dignity may take communal forms, and it may be rooted in the religious, ideological, and cultural. “What are the uses and abuses of this concept?” Moosa asked. “What are the ideological, political, and practical implications of dignity?”

“Dignity” entered into international human rights diction with the UN Charter, as a response to the horrors of WWII, and later with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity.” Cassel detailed “three circles of [legal] meaning” for the concept: firstly, that all human beings have this value; secondly, dignity as a moral justification for universal bans on outrageous practices such as genocide; and third, dignity in relation to questions of identity and the pursuit of life. When it comes to the final category, courts will often recognize there is dignity on both sides of the courtroom and dignity may operate as a limit on rights—the free speech of a speaker versus the security and social integrity of the recipient of hate speech or slander. Societies weight such rights and (in)dignities differently, as do they their recipients.

“Dignity was a moral currency prevalent in many cultures” throughout history, Moosa told the audience. Yet these same societies practiced slavery and sexual and racial discrimination. “These days,” he continued, “it is the dignity of the new tribe, the nation state. In other places, male dignity eclipses female dignity, industrial dignity eclipses communal agrarian dignity.” How can we understand these contradictions?

Power, suggested Moosa and Atalia Omer. It is the “dignity of the home team,” the dominant power group, as Moosa put it, amidst that of those with less (or no) dignity: the “ungrievable.” Cultural and moral practices, political and economic structures, offer only some people dignity and full personhood. Villa-Vicencio expanded: “if our God is an austere and indomitable God with biases towards one group against another, then sooner or later we will behave exactly as that God behaves. If we perceive the other as ‘less’ than they should be, we [will] have every right to go out and correct the situation.”

Indeed, as Omer noted, the panel was held on “Columbus Day,” alternately known as “Indigenous People’s Day.” The celebration of the Spanish “discovery” of the “new” world and simultaneous papering over of centuries of genocide of native peoples and slavery by Europeans starkly illumine the “dynamics of de-humanization that have rendered some humans ‘ungrievable.’” Drawing from Judith Butler’s Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?, Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, and W.E.B. Dubois’ travel to a Nazi-razed Warsaw ghetto, Omer considered what dignity meant for lives that “cannot be lost or destroyed because they are already lost and destroyed…they can be forfeit because they are framed as already forfeit, as threats to human lives, rather than lives in need.” These “ungrievable” lives are interconnected through modes of oppression and mechanisms of resistance. If we are to apply dignity as a “natural” right, rather than a political right for select few, we must “examine the power dynamics of dignity through an epistemology from the margins.”

In closing, Villa-Vicencio warned that we may all be more on the margins that we presently imagine. We face the threat of total extinction as a species from nuclear war, or mass starvation due to dramatic global warming. Those now most on the margins will feel this—and in the case of climate change, already do—first. It is a test of our integrity and ultimately, our ability to survive, whether we recognize their equal “grievability” and step forward with the kind of cultural transformation necessary to not only recognize them, but act on the structures that hold them “forfeit” in the first place. For this, Villa Vicencio urged us to dig through the “rubble” of discarded traditions of our faiths down to the “liberatory” core: the radical commitment to justice, and goodness, and one another.