Americans disagree profoundly over our nation’s founding ideals. Some insist that its founding principles are sound and generally govern the polity well. Others laud the egalitarian norms set forth in foundational documents but acknowledge that such aspirational ideals have far outpaced the ability or will of powerful elites to uphold them. Still others note a fundamental contradiction between abstract proclamations of universal rights and the realities of territorial theft, genocide, and enslavement on which such grand notions have depended. Within this last group, some nonetheless hold that one might find, in the wreckage of idealized histories, the possible seeds of a more just order, the appeal of which will rest in part on a claim to foundational legitimacy.

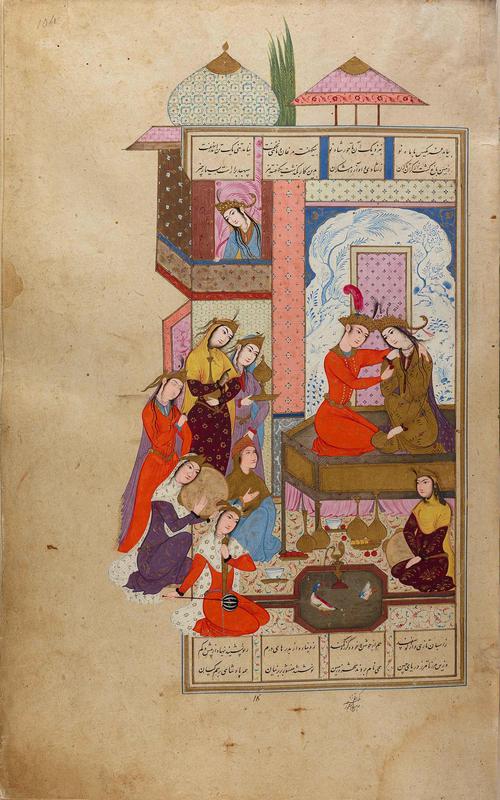

A parallel thread weaves through Zahra Ayubi’s ambitious and innovative Gendered Morality, a study of the medieval Persianate tradition of philosophical ethics (akhlaq). Ayubi carefully excavates the work of Muslim thinkers Ghazali, Tusi, and Davani, showing how the refinement of elite men’s spiritual, intellectual, and moral selves is contingent upon the supportive labor—and the willingness to be governed—of women, children, and non-elite, often enslaved, men. Wives and children also served elite men by attesting, through appropriate comportment, to such men’s ethical success as pater familias. Despite some crucial differences in their sectarian and historical contexts, these thinkers broadly shared what Ayesha Chaudhry describes as an “idealized cosmology” that presumed a hierarchical and patriarchal social order (11–12, 40).

Few Muslims today champion the elite-dominated polity, widespread slaveholding, or even male-dominated household that medieval Muslim scholars took for granted. Ayubi notes the cognitive dissonance that can arise when lay readers of Ghazali encounter disconcerting presuppositions. A romanticized expectation of timeless spiritual wisdom sits uncomfortably with elements that offend modern sensibilities. How do those with investments in the Muslim intellectual tradition deal with such conflicts? Cry hypocrisy? Reject the work as irremediably patriarchal and elitist? Ayubi takes a different tack: insisting that it live up to its implicit promise of ethical self-cultivation for all.

People navigate their attachments to foundational texts in a variety of ways. Certainly, although people occasionally describe the Qur’an as Islam’s Constitution, the parallels between how American citizens regard our national charter and how believing Muslims regard our scripture pale in comparison to the differences. Yet Americans, Muslims, and those who are both can benefit from understanding what these texts offered to their original audiences, how they’ve been interpreted over the centuries, and how they can be drawn on today.

Ayubi thinks the akhlaq tradition is salvageable. She concludes her book with a constructive “Prolegomenon to a Feminist Philosophy of Islam” not entirely dissimilar to the concluding section of Aysha Hidayatullah’s Feminist Edges of the Qur’an. In her work, Hidayatullah shifts from a thoughtful and rigorous exposition of U.S.-based women’s feminist/egalitarian interpretation of the Qur’an to her own diagnosis of aporias within that interpretive tradition and in its proposals for how feminist engagement with the Qur’an might proceed. Like Hidayatullah, Ayubi proceeds to constructive suggestions only after careful and thorough explication and analysis of the extant tradition.

Ayubi lays out the assumptions about social and familial structures at the heart of the three medieval treatises she investigates. She compellingly critiques their models of socio-sexual organization. Yet, she argues, they contain a kernel of egalitarian possibility. That doesn’t mean today’s readers of Ghazali, for instance, should simply skim past or skip over anything that doesn’t fit their notions of just families and societies. Rather, it means holding the tradition accountable for the radical implications of its core belief about human potentiality. For these ethicists, every rational self has the capacity to develop. No human being can attain perfection—God alone is perfect—but all are capable of improvement. Given this belief, it isn’t reasonable to channel all resources toward the ethical development of a small, male elite. Instead, all human beings have a right to develop their selves. Therefore, women and non-elite men must be at liberty to direct resources toward their own self-improvement, not to have their labor appropriated for the benefit of elite men who, by relying on others’ services, can devote their time and attention to refining their own capacities.

Some of Ayubi’s discussion is abstract; she attends carefully to the specialized technical terminology of philosophical ethics. But copious references to the “concupiscent faculty” aside, Gendered Morality’s basic premise is, as the kids say, relatable: the social organization of domestic labor, or the domestic organization of social labor, is a matter of power, and such power shapes who has the leisure for self-cultivation. Social and domestic labor are, obviously, organized differently in the contemporary United States than they were a thousand years ago in the heartlands of Muslim civilization. To take a single example, presumptions about mothers’ greater responsibility (if not necessarily authority) for children’s welfare are radically changed. Yet the typically unarticulated premise that some people’s time is worth more than others’ time resonates in our current climate. One need only skim recent discussions of women’s mental load or “time confetti” to see the parallels. This is, of course, not just a matter of patriarchy; the racialized and classed division of “feminine” caring labor must be central to any discussion of the just allocation of social goods. What the ethicists offer us is, in part, the reminder that ethical self-cultivation is the bedrock of a moral society. What Ayubi offers us is the assurance that a democratization of that ethical project is possible and desirable.