This conversation was born out of Mara Ahmed and Shirly Bahar’s rapport and friendship over the past 3 years. In November, they were invited by their friend and interlocutor, Santiago Slabodsky, to discuss and show their work at Hofstra University. This is a continuation of that conversation, extending what transpired between them in person and in writing, and further elaborating on their ideas about the links between Palestine, Mizrahi Jews, and the imperial politics of color. The image and concept of the injured body capture these connections.

***

Mara Ahmed: As an activist filmmaker, I attempt to spark discussions across differences and boundaries. Whether addressing anti-Muslim racism, the partition of India, or political questions related to the so-called War on Terror, I’ve relied on vox pops to gather public opinions and complicate interviews featured in my documentaries, as well as the dialogue that occurs naturally between film and audience.

In 2017, I gave a Tedx talk about colonial borders, the making of nation-states, and the absurdity of fixed national identities that flatten human multiplicities. The title of my talk, The Edges that Blur, was inspired by Adrienne Rich’s poetry. In Your Native Land, Your Life, she understands pain as a cudgel that maintains divisions but also as a bond that enables reconnection:

remember: the body’s pain and the pain on the streets

are not the same but you can learn

from the edges that blur O you who love clear edges

more than anything watch the edges that blur

I became more invested in this pairing of “the body’s pain” and “the pain on the streets,” as I began work on The Injured Body, a film project activated by Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a stunning book of poetry that stitches together narrative prose, art, and politics. As Jonathan Farmer notes in his review, the book traces Black people’s lived, deeply embodied experiences of racial microaggressions and “the ways in which the harm done by language turns to flesh, enduring at an almost cellular level.”

Rankine’s book encouraged me to document racism in America by focusing on microaggressions, what Cathy Park Hong describes as “minor feelings” or “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic, built from the sediments of everyday racial experience and the irritant of having one’s perception of reality constantly questioned or dismissed” (55).

I interviewed 17 women of color to discuss the cumulative effects of relentless microaggressions and their impact on our bodies and collective breath. The body is central. Since breath is also the gateway to expressivity in movement, I worked closely with Mariko Yamada and Rosalie “Daystar” Jones to choreograph a complementary narrative told through dance.

With embodied oppression in the forefront of my mind (as I continue to edit the film), imagine my emotion upon coming across these lines in Shirly’s book, Documentary Cinema in Israel-Palestine: Performance, the Body, the Home:

Unpacking messy entanglements and negotiations of Palestinians and Mizrahim with Zionism and Israel, the documentaries [examined in this book] politicize pain… The documentary performances of Palestinians and Mizrahim convey what Zionism and Israel look like on their skins, scalps, and faces, and sound like in their voices, speeches, and silences, portraying the structures of feeling of their pain. (2-3)

For me as a reader, there were countless such moments of recognition. And so I must start by asking you, Shirly, to tell us the story of how you came to write this incredible book.

Shirly Bahar: Documentary Cinema in Israel-Palestine is primarily anchored in three watershed moments that shifted how we view and talk about Palestine. The first moment is the early 2000s. In my book, I characterized the wave of documentaries by and about Palestinians and Mizrahim mostly living in 1948 Palestine/Israel that came out during the first decade of the 2000s, especially since 2002. Then, there is the present moment—the moment of the reception of the book. This moment in the making is a time of collective reflection on how representations of Palestine/Israel are in flux: I am thinking especially of the discourse shift we have been seeing since May 2021, when global solidarity with the Palestinian resistance to Israeli attacks outpoured on social media, at times infiltrating mainstream media too. And finally, there was the year 2014, when I wrote much of this book. Non-coincidentally, that moment of heightened awareness about how our movements have been connecting and relating to each other across struggles, and showing solidarity globally for a very long time, inspired my writing.

In the time between 2014 and now, I have been carried by hopeful pulls tightening the theoretical understandings and human bonds between those who are leading struggles for liberation around the world. One such major pull emanated from the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, and the official founding of the Black Lives Matter movement. The messages of support and encouragement pouring in from Palestine to Ferguson brought about a reinvigorated examination of the historical ties between US-based and global Black and Palestinian-led movements, and anticolonial, antiracist movements at large, as powerfully articulated by Noura Erakat and Marc Lamont Hill, as well as Angela Davis, and many others. I wrote this book as a Mizrahi Turkish-Israeli scholar. It was driven by my wish to enhance Mizrahi solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for liberation and return.

As you well know, 2014 also saw the publication of Claudia Rankine’s groundbreaking Citizen: An American Lyric. Citizen is such a special book, right? No wonder it is so highly celebrated. “Yes, and the body has a memory. The physical carriage hauls more than its weight. The body is the threshold across which each objectionable call passes into consciousness—all the unintimidated, unblinking, and unflappable resilience does not erase the moments lived through…” Rankine writes (37); I know that’s one of your favorite quotes too! Because I was deeply inspired by her writing and this quote, I made it the opening epigraph for my book. Following Rankine, and other writers committed to examining the power dynamics as well as the shared fabric of life revealed in human interactions, my book explores the deep relationalities embedded in the representations of oppression and pain of Palestinians and Mizrahim as seen in documentaries: indeed, our living conditions are unequal, yet our realities are interconnected. I love that Citizen inspired our work so much, and especially this quote. It speaks to the power of this book, as well as to how closely connected our work is.

I wrote this book as a Mizrahi Turkish-Israeli scholar. It was driven by my wish to enhance Mizrahi solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for liberation and return.

In 2014, I also flew to Istanbul to spend my first summer there since I was a child. The access that I have always had to Turkey means the world to me—it is a window into my family’s 500-year history there. That summer, my access to the Turkish language also facilitated my daily encounters with numerous visceral, visualized reports from Gaza in the Turkish media—reports that humanized Palestinian pain. What I found out, and later crafted into my argument, is that reconnecting to my home of Istanbul while sensing excessive rage, agony, and empathy when regarding the pain of others in occupied Jerusalem or in besieged Gaza, did not amount to politicization single-handedly. Rather, it takes perpetual learning and unlearning, and visual and sensorial training in reading cultural texts—it takes endless emotional labor—to try and relate to the pain of others in a deeply personal and politically committed manner.

Mara: Being a filmmaker, I am fascinated by how you use documentary film as a lens to unpack so much. You say that although oppression and racialization have impacted Palestinians and Mizrahim unequally and differently, the documentaries you discuss in the book share a political commitment and performative affinities. They defy the historical removal of the pain of Israel’s marginalized people from public visibility. You discuss how documentary performances of pain by Palestinians and Mizrahim, when seen together, invite us to contest the segregation of pain and consider reconnection. I am particularly interested in the word “performance” as it applies to the documentary form, which is supposed to be objective, an outgrowth of journalism. Could you elaborate on that?

Shirly: I wanted to analyze Palestinian and Mizrahi documentaries side by side and articulate what I thought they had in common, and the framework of “documentary performances” was just right for me to describe the affinities I identified in that corpus of work. What I saw were first-person testimonies of Palestinians’ and Mizrahim’s experiences of pain and oppression in their own words, voices, and bodies, and those were crafted visually, cinematically, as documentary performances. I used the term “documentary performance” to refer to an audio-visualized, mediated, documented, and cinematized appearance of a person in front of a camera and on a screen as part of a cinematic scene. It is a term used by Elizabeth Marquis in “Conceptualizing the Documentary Performance,” where she builds on both sociology and documentary film studies to offer “a framework for understanding and discussing the documentary actor’s work … which takes into account everyday performative activity, the impact of the camera, and the influence of specific documentary film frame-works (45). The book engages an approach mostly drawing on visual culture and performance studies, thinking through a person’s performance as a human medium in constant conversation with the filmmaker, filmmaking apparatus, and mechanisms, and teases out some of the most quintessential questions informing film and documentary studies as a whole—questions about authenticity, mediation, and the construction of reality in representation.

I was interested and wanted to participate in the efforts to revisit the term “performance” by documentary scholars studying reenactments, such as Jonathan Kahana and Bill Nichols. But it is important to note and celebrate—and I do in the book—that the complex, inspiring understandings of “performance” and “performativity” in all of their overlaps, have been theorized by queer and feminist scholars firstly, emerging at the intersection of gender and sexuality studies and critical race studies since the 1990s. Diana Taylor taught us that performance “function[s] as vital acts of transfer, transmitting social knowledge, memory, and a sense of identity,” that operates as part of the overall “aesthetics of everyday life” (2–3) Judith Butler’s landmark theorizations of “performance” and “performativity” heavily drew on J. L. Austin’s How To Do Things with Words. Along similar lines, Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick and Andrew Parker differentiated between the theatrical “performance,” and the linguistic, discursive term of the “performative.” Crucially, Sayidia Hartman illuminated the need to consider performance and performativity together (alongside her theorization of pain as relational): “the interchangeable usage of performance and performativity is intended to be inclusive of displays of power, the punitive and theatrical embodiment of racial norms … the entanglements of dominant and subordinate enunciations … and the difficulty of distinguishing between [them]” (5). This interdisciplinary push is required where documentaries are concerned, and especially in the digital age of accelerated visual popular culture defining our contemporary everyday.

Above all the performative trends that the documentaries share, I found, is their invitation to understand pain as relational through taking in and connecting to the embodied documentary performance we are viewing. As interactive sites of testimony, the documentary performances powerfully politicize pain by shaping it as a relational event that took place between the performing person and the state, and is lingering in the person’s body and ways of speaking, expressing, and representing themselves to this day. The documentary performances are multilayered encounters between bodies, affective states, speeches, and filmic apparatuses, in which the films’ participants return to the past, formative painful experiences that they still embody and endure. The hit of the bullet, the demolished home, the lost carob tree, the dried fountain, the unattainable moon, the imposed mask, the interior of the home, the fence of the camp—are all imagery communicating particular ways of living, hurting, being in, resisting, and becoming through political conditions of oppression. Sharing their told, filmed performances, the participants invite us to feel the trajectories of an oppression that became pain with them, and relate to their experience of living on.

Mara: There is one sentence in your book which hit me hard. It is the commonly held notion that you cite, claiming that “the trauma of witnessing destruction directly harms the usage of language about it” (30). To me this means that the credibility of language (and therefore people’s testimony) is damaged by violence. Consequently, those who are occupied (on whose minds and bodies violence is constantly enacted) are never seen as credible witnesses of their own pain, of their own lived experiences, based on dominant codes of credibility. Many of the women I interviewed for The Injured Body, for example, spoke about gaslighting—microinvalidations which make them second guess themselves and question their own sanity. You take issue with this notion. Could you tell us more?

The documentary performances powerfully politicize pain by shaping it as a relational event that took place between the performing person and the state, and is lingering in the person’s body and ways of speaking, expressing, and representing themselves to this day.

Shirly: You’re absolutely right, I agree that the idea that trauma directly harms expression runs the risk of dismissing and gaslighting those who underwent and/or witnessed it. And I have always been struck with how commonplace it is in Freudian psychoanalysis, and in literary and film theories that employ psychoanalytic frameworks. Critical thinkers, especially in gender and queer studies, such as Lauren Berlant have contested this idea; thinkers such as Sara Ahmed even use the word “pain” rather than trauma to politicize harm and injury—I think intentionally. I follow these thinkers in taking issue with that idea and apply my criticism to film analysis, especially in chapter 1, when I analyze the documentaries Jenin Jenin (Mohammad Bakri, 2002) and Arna’s Children (Juliano Mer Khamis, 2003). There, I show that when testifying to horrors that they have witnessed, the witnesses in the documentaries do not guarantee to posit “what had exactly happened” with any measure of empirical accuracy. Rather, the documentaries’ approach underlines whose pain gets to be filmed and shared depending on the circumstances of power informing the distribution of representation.

Yes, it has been established, the trauma of witnessing destruction directly harms the usage of language about it. But—and that’s a big but—on top of running the risk of unifying and depoliticizing the diversely positioned human experience, the Freudian genealogy of trauma carries harmful legacies of disbelief toward survivors. In this chapter, I harness a politicized view of both the testimony of trauma and of documentary distribution in Palestine/Israel to show that the precise ways in which their testimonies have been performed and cinematized, including the testifiers’ bodily gestures, chosen words, silences, and general edited sequences, provide spectators with poignant clarity regarding how pain hit their bodies when the bullet hit the executed person. Additionally and no less importantly, the testimonies communicate how the conditions of the military occupation that pulled the trigger also made it difficult to communicate the pain of that experience outside the camp, by depriving them of audiovisual means of communication, and painting all the camp residents as unreliable speakers perforce, who were responsible for their own suffering. When testifying in the films, the witnesses’ reenactments of the pain of witnessing destruction politicize their pain, framing it collectively and relationally—as injuring their bodies and mental and affective states, as well as recovering by their very telling of their stories of embodied and psychic pain. In that way, they transform from racialized and potentially targeted innate “terrorists”—whose pain is their own fault—to survivors with agency over their own becomings, personally and collectively.

Mara: I would also like to bring up the constant threat of violence—of the military mainly in the West Bank and Jerusalem, and the police within the 1948 boundaries. You talk about documentaries showing Palestinian children experiencing “withheld violence,” and lingering on the threshold of death long before they die. Your words reminded me of Frantz Fanon and the “muscular contraction” of the colonized body. In fact, we shot a dance sequence titled Emancipated Breath (a prelude to The Injured Body) which addresses the policing of bodies, the containment of their breathable atmosphere, and the yearning for release. Could you explain what this implies in the Palestine/Israel context?

Shirly: It is something I observed when analyzing Arna’s Children which I mentioned above. Arna’s Children extends the message that Bakri put out there, of resisting the Israeli silencing and gaslighting of Palestinian pain. This documentary does so especially by delving into the structure of feeling of living with potential death—of a beloved one, or one’s own—throughout life. The documentary follows the wonderfully inspiring children and teenage theater students of the Freedom Theater, run by Arna Mer, Juliano’s mother, and himself. The documentary traces how these young people lived with the encompassing threat of death under military occupation much before many of them died. The formative, horrific experience of knowing the probability of death intimately in life is not only collective, but also one that challenges the temporal understanding of pain: rather than a past event, the pain of living with death is present and constant and projects onto the future, all at the same time.

In a very different way, and while they have access to Jewish privilege and supremacy, Mizrahim have been experiencing the heavy hand of police brutality too. I write about those experiences when analyzing films exploring the massive crackdown on the Mizrahi Black Panthers in Jerusalem in the 1970s—films such as Kaddim Wind (David Ben Chetrit, 2002), Have You Heard of the Black Panthers? (Nissim Mosak, 2002), and The Black Panthers Speak (Sami Shalom Chetrit and Eli Hamo, 2003). Beloved filmmaker David Ben Chetrit died of complications in the aftermath of an atrocious battering by military security forces, in the heart of Tel Aviv. But even before the first Black Panthers’ demonstration, young Mizrahi leaders of this groundbreaking movement have had to deal with police brutality, basically all throughout their upbringing: many of them would get beaten up and/or sent to juvenile prison upon merely entering the public sphere. For young Mizrahim, walking down the streets was prohibited regularly regardless of any crime they might have committed. These beatings mark the criminalization of Mizrahim’s appearance in the highly policed public sphere, thus enforcing and enabling their exclusion from it. The testimonies in the documentaries about the police’s continuous criminalization and repeated public battering paint a larger picture of the state’s racialization that Mizrahi bodies have been enduring ever since they arrived in Palestine/Israel.

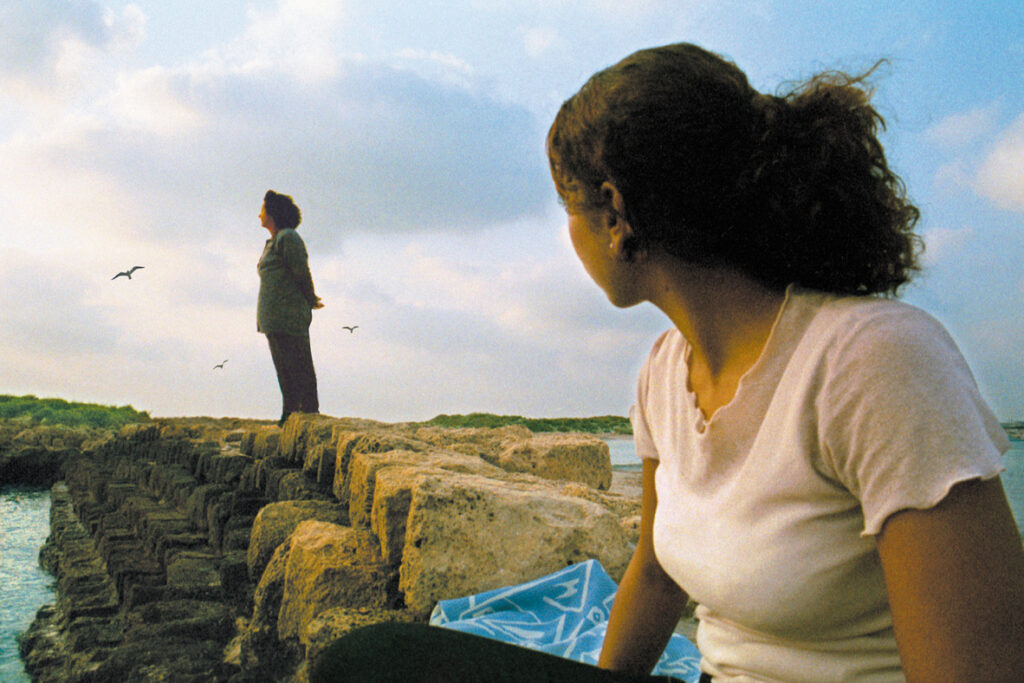

Arna’s Children from Trabelsi Productions on Vimeo.

Unlike Palestinians, Mizrahim’s access to Jewish privilege generally allows them to dodge the constant threat of death. To earn this privilege and enter the Jewish fold, however, Mizrahim are forced to go through a process of assimilation that involves shedding any connection to Arabness and becoming as “purely” Jewish as possible. Palestinians and Mizrahim were historically differentially positioned in relation to Jewish supremacy, society, and Israel’s system of state security—positions that are further instigated at times of heightened violence, as the films show. Sadly, Mizrahim actively participate and often lead the work of the military and police to enhance violence towards Palestinians. They have been intentionally recruited into the police since the 1950s, not unlike the intentional recruitment of people of color into the police in the US. There have also been rare, yet deeply inspiring, cases of Mizrahi organizing in solidarity with Palestinians. Kaddim Wind follows organizer Oved Abutbul who, as part of his grassroots campaign against the eviction of Mizrahi residents from Mevaseret Tzion in 1997, joined a community of activists who rented a bus to Jericho, in the territory of the Palestinian Authority, to seek asylum. Additionally, the activists sent a letter to the king of Morocco, asking to return there with his blessing.

Mara: I would like to end with something you say in the book, that “more often than not, those who care for the pain of others are found in relative vulnerability themselves—political, physical, mental—thus chancing their becoming further undone” (26). Meaning that many times, those who feel the pain of others most deeply are themselves living precarious lives. I think of the Black Lives Matter movement and its principled support for justice in Palestine. I would love for you to expand on this important point.

Shirly: I thought the same, and it’s at the heart of my writing! As I started saying above, I feel hopeful when I see those who are leading struggles for civility and liberation around the world, express and act in solidarity. After 2014, we saw these connections nourished further over the years, perhaps most notably in 2020, as demonstrations to protest the killing of George Floyd and so many other Black people in the United States throughout history and right now, swept across the world—a world hit by a global pandemic disproportionately harming the most vulnerable and racialized populations. Understanding the interconnectedness of Palestinian struggles and Black movements reaffirms them as core inspiration for many historical anticolonial and antiracist movements around the world, including the Mizrahi struggles in Israel/Palestine, especially those that emerged from the 1970s Black Panthers movement in Jerusalem. Yet, as Mizrahim, we have to reckon with our position of privilege and proactively acknowledge it. In the introduction to the book, I positioned myself in the field as a Turkish Israeli Mizrahi scholar with Jewish privilege in the Jewish state of Israel—where I am from—and with the privilege of visiting Turkey, also where I am from, unlike many of my fellow Arab Jewish Mizrahim. This attempt to transparently explicate my identification and viewpoint from the outset fuels my intersectional intervention of considering interrelated oppressions and relational pain.

In acknowledging our indebtedness to interconnected, anticolonial and antiracist movements, especially Black and Palestinian ones, and in endorsing our solidarity with them, I am encouraging more Mizrahi filmmakers, scholars, and organizers to also step forward. To that end, my book advocates for the transformative power of relating to another fellow human’s mediated vulnerability and taking on the risk of complicating, confusing, and even adding to our immediate experience of our own pain, for the sake of holding space for their humanity in ourselves. That quote from my introduction you mentioned above, comes right before I myself quote Tourmaline, who writes in her preface to the gorgeous new edition of The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions: “If we are to ever make it to the next revolution, it will be through becoming undone, an undoing that touches ourselves and touches each other and all the brokenness we are … to become undone is the greatest gift to ourselves” ( viii). Documentary Cinema from Israel-Palestine hopes to be of interest to anyone who wishes to understand their own feelings of powerlessness as not one with them privately and naturally but, rather, as public, political, relatable, and changeable.