When I introduce students to Islam in my undergraduate courses, I always feel a little nervous. I am a scholar of Catholicism, I know no Arabic, and like everyone with a graduate degree in the humanities, I was trained in the pernicious histories of western appropriation of Islam well. At the same time, I have a deep sense of moral responsibility to teach at least some Islam in introductory theology courses. The vast majority of my undergraduate students come into the classroom with either a blank slate when it comes to Islam, or, more likely, with their heads full of disconnected snippets of Islamophobic images and narratives culled from growing up on a media diet in the post-9/11 United States. Add to that, Islam isn’t “other” or “out there”; there are always devout Muslim students in my theology classes too, usually first-generation students commuting from elsewhere in the Bronx, Queens, or Manhattan.

I begin teaching Islam always with trepidation, but I usually reclaim some confidence once I’ve introduced a line from Carl Ernst’s preface to Following Muhammad. He describes learning about Islam as a practice in which “the reader participates in the creative act of reimagining as human an immense group of people who have been demonized.” We talk a lot about the moral stakes of what Ernst calls “restoring a human face to Islam” (xxi). I’ve had a lot of success with documentaries like The Light in Her Eyes, anthropological work like Caroline Moxy Rouse’s Engaged Surrender, and this set of interviews with Muslim scholars who describe their work in personal terms. These are all deeply effective and humanizing materials.

But my nervousness inevitably picks up again, because the truth is, in my heart I love teaching most of all the mystical and poetic texts of religious traditions. There are few teaching memories I have that are more joyful than introducing students to the beauty of Rumi and Hafez from Omid Safi’s Radical Love, or discussing podcasts like this one, or even having incredible musicians like Dan Kurfirst and his band sing Rumi’s poetry accompanied to music. But of course, a unit on Islamic mysticism is besieged with dangers on every side: the risk of perpetuating orientalist fantasies about the pure Sufi kernel in an otherwise legalistic and dry religion. I try and tackle this head on, but I still struggle to connect Islamic poetry and mysticism to the larger pedagogical project of humanizing Islam. The students find the material beautiful and unexpected, but it’s hard to shake them of the idea that these poets merely illustrate a rarefied world of elite male writers, and that studying them is akin to peering into a museum. Some classroom discussions have veered disappointingly towards stereotypes that perhaps Islam “used to” be beautiful, playful, spiritual, but no longer. I sense these stereotypes always loom darkly at the edges of my teaching, and despite different pedagogical experiments tackling it, I never felt like I dealt with it satisfactorily. I always felt uneasy.

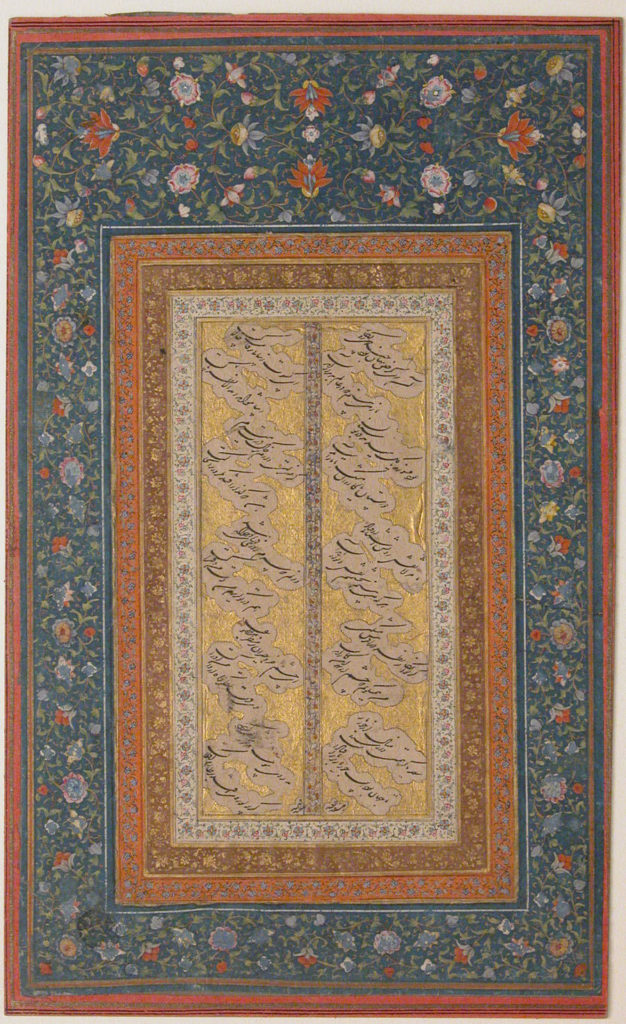

Then along comes Niloofar Haeri’s masterful new book, Say What Your Longing Heart Desires. It is a beautiful, concise, and thought-provoking work, analyzing a community of women in post-revolutionary Iran whose religious lives are centered on the poetic and mystical materials of Islam, what she calls ‘erfān. The word ‘erfān has a wider connotative range than the words mystical, poetic, or spiritual have in English. The latter usually signal something that is done privately and interiorly. ‘Erfān, as Haeri describes it, is a communal practice through and through: these women grew up in Tehran memorizing and performing the poems of Hafez and Rumi at family parties, listening to poetry competitions on the radio, and keeping elaborate notebooks filled with transcribed mystical poems as teens. As adults, they host lunches and dinners where friends read poems and prayers for discussion and debate. It is these intensely relational settings in which Islamic interiority is cultivated.

The truth is, in my heart I love teaching most of all the mystical and poetic texts of religious traditions…But of course, a unit on Islamic mysticism is besieged with dangers on every side: the risk of perpetuating orientalist fantasies about the pure Sufi kernel in an otherwise legalistic and dry religion.

The book’s title comes from a famous dialogue in Rumi’s Masnavi, where Moses tells a shepherd what God has revealed to him: “Don’t search for manners and rules/Say what your longing heart desires.” The line embodies a central ‘erfān idea, that of the heart as the innermost and truest place out of which the pure love of God radiates (13). Readers already familiar with Rumi will recognize his characteristic vision of God, but Haeri’s work completely brings it to new life. Now, suddenly, we don’t read this only as evidence of the 13th century Persian Sufi genius, but we also see it as a theological vision that has been kept alive, circulated, debated and prayed with in the hearts and minds of people all over Iran today, particularly women.

One of the most interesting points Haeri makes concerns how this culture of ‘erfān emerged in Iran. Following the 1979 revolution and the end of the Pahlavi monarchy, Iranians experienced a succession of Islamicists consolidating power who aimed to Islamize society at every level. Many Iranians, of course, complied and promoted this vision, while others, such as secularists who remain allergic to anything religious, resisted. But for a huge swath of the culture, something subtle happened—a robust culture of laity began to take the Islamic materials into their own hands, and join in arguments about topics like what a true Islam looks like, the nature of God, and religious sincerity. Many of these people were drawn by the mystical and poetic materials and engaged them with urgency: the stakes, as Haeri puts it, were high in a way that was never true previously. Before 1979, most people mostly left Islam in the hands of the clerics and elites. Little was at stake because much of it never touched their lives. Now, on the other hand, nearly everyone has gotten into the game of religion.

But more than an overview of an understudied cultural phenomenon, the brilliance of the book lies in Haeri’s analysis of the dynamic emotional, spiritual, and intellectual landscape of a group of people who are typically obscured in studies of Islam: educated, middle-class lay women. For example, in Chapter 1, “Where Do Ideas Come From?” Haeri argues that the prayers and mystical poems the women memorized made the religion real for them, but not just because of what the poems were “about” (the meanings of many mystical poems are not exactly clear). The memorization of poetry also served as an aesthetic and “pedagogic” practice that contributed to the cultivation of a literate, good, and moral person. A person with a head and heart full of Hafez, Saadi, and even women poets whose names were new to me, like Parvin Etesami, would learn to cultivate ādāb, inner and outer refinement in ethics, character, and aesthetics. The practice of memorizing poems and sharing them publicly also enable the women to “acquire performance skills and quick wittedness, they hone their skills in memorization; they use it to express feelings and they learn to think about religion in imaginative and paradoxical ways” (45). Drawing on theorical material on sacred presence, Haeri also shows how the memorization of poems and prayers make present non-ordinary reality to the believer. One woman describes, for instance, how uttering a poem as an adult that she memorized as a child makes present a long-dead parent, while another woman describes performing her daily ritual prayers and imagines herself at Mecca, even standing before the Prophet (66-67).

Memorized poems also become the material out of which the women practice do’ā, or spontaneous prayer to God, the subject of chapter 3. In this chapter, the women’s voices are most central and most personal, with Haeri describing their intimate and serious dialogues with God. When it comes to spontaneous prayer, she writes, the women “make it up as they go along, using their imagination, their experiences, and whatever related sources they may have been exposed to, such as poetry, prayer books, the media, and discussions with others…God is neither conceptualized nor worshipped in just one way. The relationship with God is capacious and experiences vulnerabilities and ruptures” (123). What a vivid image to contrast to U.S. stereotypes of Muslims who “submit” to God uncritically and monolithically. These women are full of doubt and creativity.

In the end, I truly cannot think of a more compelling book that can do the work of (returning to Ernst’s phrase) “restoring a human face to Islam.” Scholars have long aimed to combat stereotypes of Islamic legalism and politization by introducing students to the mystical visions of Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi. But this book helps us do so much more than that—it enables us to keep this mystical language alive in our classroom while making sure we don’t ossify it as the orientalists did, and only see it as part of Islam’s past, the domain of rarefied male elites, and as disconnected to living Muslims today.

At the present of my writing this piece, we approach a new academic year in the midst of another COVID resurgence. It is quite honestly hard to face it with anything but dread. But when I imagine a day this coming year, maybe back in the classroom, reading some beautiful poems from a collection like Radical Love, then reading Say What Your Longing Heart Desires with my undergraduates, I start to feel something like the rushes of actual excitement, something much more powerful than nervousness or even dread. I am so grateful to Niloofar Haeri for this extraordinary book. I can’t wait to share it with my students.