Rajbir Singh Judge begins his book by stating that it is a historical narrative that refuses to historicize. Indeed, the book is staged as a series of refusals. On the one hand, Judge probes how a people and a tradition grappled with loss, and on the other hand, he addresses the problem space of history itself through refusal. However, these are not two disparate modes of engagement. Rather they are intertwined throughout the book, ebbing and flowing through the five chapters. As he puts it, “writing a narrative of a historical figure such as Duleep Singh is itself a bid to come to terms with the failure and narrative of history” (183).

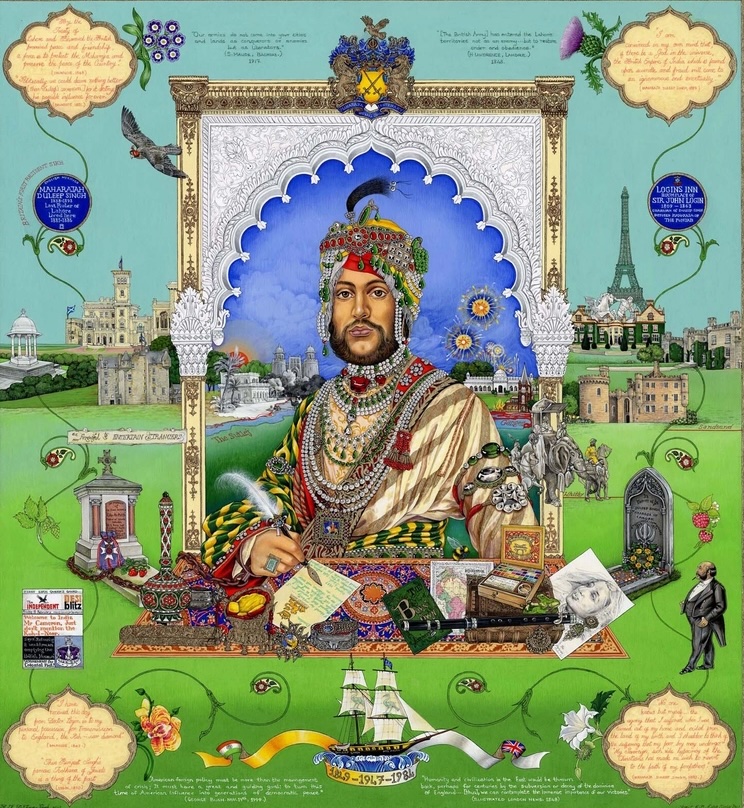

Prophetic Maharaja provides an opening to rethink well-worn questions about loss, sovereignty, community, and encounter, through the sophisticated weaving together of critical theory, anthropology, psychoanalysis, and of course, the writing of history. Judge takes Duleep Singh, the last Maharaja of the Sikh kingdom, and his deportation (at age ten) after the British East India Company’s annexation of Punjab in 1849, as his starting point. Singh is forced to give up his title and sovereignty over Punjab, converts to Christianity at age fifteen, and is soon exiled to England. In examining how Sikhs responded to the loss or dissolution of the Khalsa Raj between the mid- to late-19th century, Judge refuses an approach that privileges the restoration of that loss. Key to his reframing, therefore, is a contending with loss as opposed to its recovery. It becomes clear at the outset that this book is resolutely not invested in the historicist desire for closure or to uncover an authentic past, a “real” Duleep Singh. Rather, the conceptual framing of the book unfolds in the tensions, ambiguities, and gaps between the colonizer and colonized, memory and loss, individual consciousness and sangat (community), and importantly, between history writing as we know it, and history as an always incomplete endeavor. In other words, Judge invites us to dwell on the temporality of intellectual traditions (such as psychoanalysis and subaltern studies) and intellectual history more generally. It is precisely this methodological and analytical move that marks Judge’s novel contribution to South Asian history.

There are, nonetheless, certain historical truths that need to be stated before getting to the question of loss, such as the colonial government’s constant thwarting of Duleep’s Singh’s attempts to return to India because they feared a political revolution. Drawing on archival research, the author traces this history clearly. What is more unwieldy, yet a far more absorbing narrative at the core of the book, is the set of desires and fantasies attached to notions of loss, sovereignty, and community. As Judge puts it, he is more interested in dwelling in the various rhythms of loss, than providing a theorization of loss. This is another kind of refusal in the book: “My project refuses the wager of authenticity and continuity, but also, crucially, absolute and transhistorical loss” (22).

The book is staged as a series of refusals. On the one hand, Judge probes how a people and a tradition grappled with loss, and on the other hand, he addresses the problem space of history itself through refusal.

In working through this refusal, the book also hews close to the Sikh tradition itself. In other words, instead of writing a history of the Sikh tradition or of Duleep Singh’s life using the secular categories of professional history, the author uses the Sikh tradition as a conceptual resource—concepts such as hukam (order, command), naam simran (to remember continuously), and amrit (the nectar one imbibes to join the Khalsa), among others—to think with and through the notion of loss. In this way, and following scholars such as Talal Asad, Judge pays close attention to the genealogy of concepts, especially the concept of tradition, and how they might enable and disable our understanding and writing of history. If the Sikh tradition is a singular one that continually strives for coherence through a simultaneous engagement with internal contestations, frictions, and discrepancies, then how does one inhabit such a tradition? And is there a tension here between the tradition’s own internal coherence, or striving for coherence, and the analytical move that the author makes in resisting coherence, if coherence is understood as a hardening of tradition?

One way in which Duleep Singh inhabited the Sikh tradition was by constituting a community, a dislocated community, from afar through his regular letters, what the author refers to as “hidden transcripts” (following James Scott’s definition). This active community-making through the invocation not only of blood and kin-ties, but also the Sikh tradition itself, is an example of how events in the past constantly exceeded the grasp not only of the colonizing power, but also of historians seeking a totalizing narrative of Duleep Singh as person and impending sovereign. He is a prophetic maharaja, Judge argues, because “prophecy refuses to abide by the logic in which past, present, and future proceed sequentially” (19). And this anti-teleological move is one that we see throughout the book.

Inhabiting Tradition

I want to briefly focus on chapter three, which examines Duleep’s Singh’s conversion to Christianity and reversion to Sikhi, since it provides a compelling response to the question of how one inhabits the Sikh tradition, especially in wading through the murkiness of its encounter with colonial modernity. For too long, narratives of conversion have been tied to the question of belief or individual consciousness. The author not only disentangles conversion from its intellectual genealogy that is rooted in Christianity, following scholars such as Talal Asad and Gauri Viswanathan, but argues that it needs to be examined from within the context of Sikh ethical and embodied practices. As he notes, it is not as though individual consciousness is completely absent, but rather, it must “conform to the ethical practices and bodily disciplines prescribed by within the Sikh community in which the experience of learning was valued above individual decisions” (101). In Judge’s analysis, this is neither simply a return to emic concepts nor a complete disavowal of subjective consciousness. Instead, it poses a challenge to the logic of colonial modernity as well as to the Sikh tradition that is itself transformed in its encounter with British colonial rule.

So how do we understand Duleep Singh’s conversion or reversion from within the Sikh fold? In this chapter, we see how Duleep Singh oscillates between the individual self and the sangat, caught in the epistemic murk of colonial rule. Judge borrows the term “epistemic murk” from anthropologist Michael Taussig to refer to the murkiness or uncertainties that accompanied colonial-era policies and decrees. This becomes clear in the example of the colonial state’s policy of noninterference in religious affairs, which ironically requires a colonial officer to be present when Duleep Singh interacts with other Sikhs in Aden for his reversion ritual. This contradiction destabilizes the public/private binary that the colonial state strives to maintain. When Duleep Singh enters the Khalsa, he is neither beholden to his individual self, nor the colonial state, but to the entire body of the Khalsa and the Sikh tradition. In this way, epistemic murk also constitutes a form of resistance as anthropologist Sophia Chao has recently argued: “…a refusal to reduce any particular entity to any singular, static reality, and instead a recognition of any being or body’s positioning with broader systems of power and vulnerability” (41).

When Duleep Singh enters the Khalsa, he is neither beholden to his individual self, nor the colonial state, but to the entire body of the Khalsa and the Sikh tradition.

In closing this chapter, Judge briefly touches on theories of value to further assess the murkiness of Duleep Singh’s tensions and entanglements with colonial rule and the sangat. Take karah prashad, sacred or blessed food that is distributed to all at a gurdwara. Common across sacred sites in India and across different religious traditions, the giving or taking of sacred food is embedded simultaneously within reciprocal ritual relations, capitalist market logics, and the maintenance of social and kin ties. In other words, the efficacy of collective Sikh prayer, karah prashad, and the commodity form are all knotted together. It is this knotting that irritates and confounds colonial administrators, who further intervene and regulate the religious affairs of their subjects, subjects whose practices often exceed presumed boundaries between public and private, religious and political, and individual and collective. And this chapter is a fantastic instantiation of this kind of excess, and the ways in which people act in unexpected ways. As literary theorist Terry Eagleton puts it in his book The Ideology of the Aesthetic, “there is something in the body which can revolt against the power that inscribes it” (28). We see this repeatedly in Duleep Singh’s string of attempts in his adult life to revert to Sikhi, challenging colonial officials’ assumption that his conversion to Christianity at age fifteen and subsequent exile to England would distance him from any plans to overthrow the empire and reclaim the Khalsa Raj.

Ultimately, I find convincing Judge’s refusal to offer a solution or answer to questions that have typically been asked about the past, especially in their tracing of an all-too neat historical narrative about the loss of the Khalsa Raj. And there are lessons to be learned here that apply to other contexts, especially in colonial South Asia. What is particularly engaging about Prophetic Maharaja is the double move that Judge makes: he takes us through how Sikhs contended with loss, but the book is also about Judge’s own contention with the waxing and waning of certain intellectual traditions within the academy, such as subaltern studies and psychoanalysis.

In thinking with Judge’s series of refusals, as an anthropologist, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to Audra Simpson’s work on refusal which is tied to questions of sovereignty and indigenous politics in the North American context. On the one hand, refusal is embedded in the everyday acts of people, and on the other hand, it is also a theoretical and methodological move. This “ethnographic refusal,” says Simpson, “acknowledges the asymmetrical power relations that inform the research and writing about native lives and politics” (104). It is therefore an act of resistance against using the theory and methods of a discipline in ways that could compromise tribal sovereignty, but it can also be a decision to not make certain information available for the academy. And this is an ethical intervention. Similarly, I see Judge making an ethical move, both methodologically (the refusal to provide a cathartic end point) and in tracing the ethical projects in which the book’s historical actors are invested. In this way, refusal remains a potent idea across disciplinary silos, and the refusals in Judge’s book offer provocations that scholars of South Asia and beyond will be contending with for some time.