“There ought to be a rule, strictly enforced,” Walter George Smith wrote in 1921, “that where a Gregorian, Jewish, Catholic or Protestant Institution is caring for orphans of its own faith, that equal subsidies per capital be paid to them, and that was the rule as I remember it . . .” Smith, a Catholic lawyer from Philadelphia in the employ of the Protestant-dominated American aid organization Near East Relief (NER), sent the letter to NER’s director advocating on behalf of Franciscan Sisters operating an orphanage in Urfa, in modern-day Turkey. Amidst rising tensions between Protestant staff in the field and local Catholics concerning aid distribution and religious instruction, the letter was indicative of the quandary relief organizations in the Near and Middle East found themselves in after World War I: how to adjust their practices within a changing environment marked by religious pluralism and state secularism. For his part, Smith acknowledged devout Protestants could not be expected to easily smooth over tensions with Catholics but that such a policy should be publicly proclaimed and enforced, “both because it [is] right and because it [is] expedient to be absolutely fair and impartial.”[1]

Indeed, a year later, victories by the forces of Kemal Atatürk paved the way for the emergence of Turkey as a new nation-state from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Led by Atatürk, the new Turkish authorities advanced a secular nationalist domestic agenda which further complicated NER’s relief efforts as they expanded to increasingly diverse populations across the region.

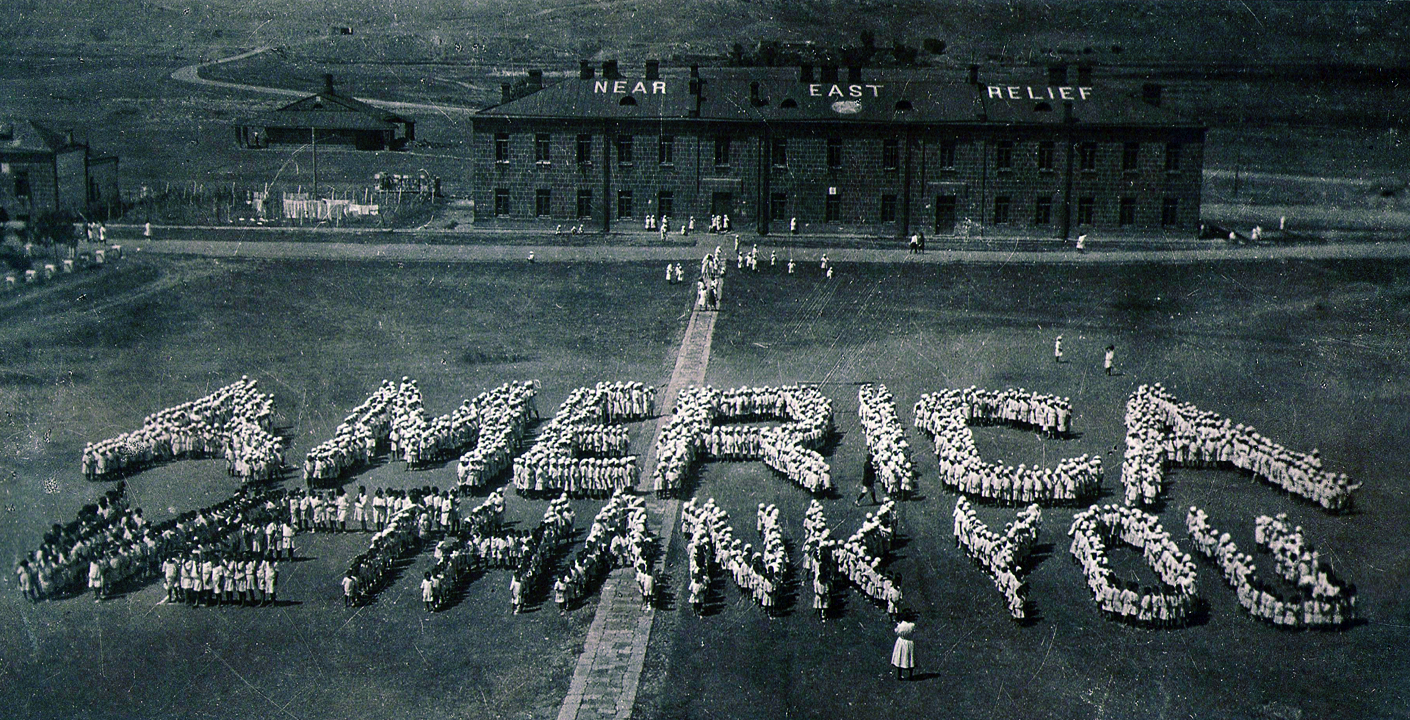

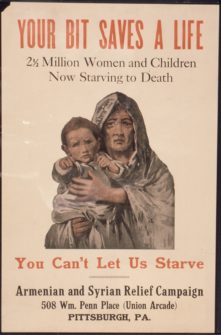

Formed during WWI, NER was a marriage of American philanthropic and Protestant missionary entities which administered primarily to Armenian refugees in the wake of Ottoman-led massacres and forced-displacements. With a special emphasis on caring for Armenian orphans, the needs of these children—most notably religious care and long-term employment or means of self-support—drove NER’s turn in the 1920s from a relief organization to a development organization primarily focused on raising standards of living in rural farming villages. However, as Smith’s letter illustrates, NER’s expansion into development was preceded by and continued to grapple with the question of working within pluralistic contexts and secular state policies. NER officials in support of the organization’s new orientation favored a holistic, human resources-based approach to development that integrated cultural-revival with nation-building. They focused on technical training, small-scale adjustments to existing practices, and, above all, the expansion of education adapted to local contexts and rural needs. Many officials being devout Christians, religious instruction remained central to such a development agenda, primarily in crafting a new generation of local leadership marked by strong moral character.

At a time of such change and uncertainty in the region as the 1920s, many within NER saw their goal as building prosperous, harmonious nations with responsive states. Pragmatically, therefore, the push was to work within new host-country guidelines and policies, many of which, like Turkey, feared inviting Western colonial influence and thus forbade proselytism or non-Islamic religious instruction. NER had concrete evidence: missionary schools within Turkey were forced to adjust, move, or close their doors; otherwise, as some missionary personnel found, they faced arrest. In order to simply maintain an ongoing presence, accommodation to the new secularized environments was necessary. Moreover, given the increasing challenges of pluralism that Smith’s letter demonstrates—with NER juggling a coalition at home and working with diverse partners in the field—overt proselytism was jettisoned in favor of what became called a “non-sectarian” approach to development and education.

The more optimistic among NER staff hoped their approach would set a positive example of Christianity-in-action, a Christ-like model whose wisdom and tolerance would eventually win converts. In this regard, NER officials were able to draw on contemporary trends in missiology that, recognizing God’s ongoing presence in all peoples and faiths, emphasized tolerance and the superior effectiveness of a non-sectarian approach to evangelism. Christian missionaries were not to displace other faiths, but to offer education and services to all as a way of demonstrating Christianity’s superiority. The path was clear for NER to engage in development work among not only Christians but also Muslims in the region. The paternalism of earlier missionary work, therefore, lived on in altered form and a consequential tradeoff was a handicapped ability to advocate on behalf of victims of state oppression, as NER had done during the genocide (see Watenpaugh 2015).

So what does all this mean for how we understand purportedly secular development practices today? NER’s adjustment to pluralistic and secular contexts—namely, in adopting a non-sectarian stance—can be viewed within the vein of religiously-neutral service organizations such as Rotary International (p. 228) and the Rockefeller Foundation adopting the humanitarian and service orientation of missionaries while emptying them of Christian symbolism and content. However, the NER move—culminating in the formation of Near East Foundation—was largely a pragmatic adjustment that enabled continued provision of spiritual support. To be a non-sectarian organization, therefore, cannot be conflated with being a secular organization. Nonetheless, it was the non-sectarian orientation that set the example “religiously-affiliated” non-governmental organizations (NGOs) would follow in the wake of World War II.

Contemporary NGOs continue to grapple with the paradox this move created: working within certain structures and guidelines in return for a seat at the table—a chance to continue to serve. The task for those engaged in development work is to be reflexive about the sources of their current practices and the lingering traces of historical biases that work against multi-perspectival orientations and remain inadequately attuned to local power hierarchies.

[1] Letter from Walter George Smith to Charles Vickery, February 5, 1921, Rockefeller Archives Center, AC.2010.002, Box 1, NER Minutes 1920-1921.

Featured Image Credit: Boy Scouts of America – Boy Scouts of AmericaSource site: CC BY-SA 3.0. “Jackie Coogan. The Boy Scouts and child actor Jackie Coogan helped fill a «million-dollar milk ship» for Near East Relief in August 1924. During the campaign, the admission price to any Jackie Coogan movie was a can of milk.”