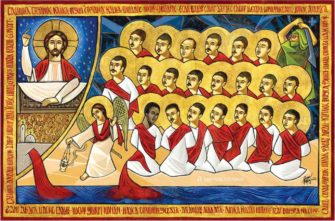

At the heart of Angie Heo’s remarkable book is her demonstration that “saints are not anachronisms” (253). In her ethnography of contemporary Christian and Islamic life in Egypt, the living and the dead mingle. The dead return through memorialization (pilgrimage, relics, icon veneration, hagiography, liturgy), and the living take up the intimacy of this renewed bonding. Perhaps, in fact, we might rather say that all this is wildly anachronistic from a modern historiographical point of view—in which the aim is to rigorously preserve the past as such [1]— showing anachronism to be politically and socially powerful in modern Egyptian life. As Heo’s book repeatedly demonstrates, devotion to the holy dead shapes the horizons of possibility for the living—and those dying in the present. The Epigraph to the book’s final chapter is taken from a liturgical commemoration of the “New Libya Martyrs,” who were 21 Christians beheaded on February 15, 2015 by ISIS, and whose deaths were recorded and disseminated through the internet [2]: “Martyrs of the new covenant/Their blood was renewed/And their remembrance became a feast day” (237). The blood of the victims is renewed—purified—by the red baptism of martyrdom. Their deaths also renew the blood of martyrs past, including Christ’s. Recall Tertullian’s famous second-century dictum: “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”[3]

What forms of belonging do the memorialization of martyrs, ancient and new, make possible in the present? What uses do the living make of the dead? As Heo notes, “The Coptic Church is reinstituted across each act of remembering scenes of holy suffering and violence” (38). But the mobilization of memory through historically situated narratives that frame their deaths leads to very different communal boundaries, calibrating and foreclosing “horizons of Christian-Muslim belonging” (242). Important here are the ways in which the Libya martyrs were deployed as part of Sisi’s war on terror, a strategy related to his domestic project of suppressing Islamist elements in Egypt, beginning with his crucial role as commander of the Egyptian Armed Forces in the coup that deposed Morsi, an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood. This use of the martyrs by Sisi produced ambivalent effects for Copts. Seeking to forge a collective Egyptian identity, the state placed the martyrs under the supra-confessional rubric of the nation. Deeming the cause of their deaths “terrorism” rather than “sectarian” violence, the murders were interpreted as “attacks on the nation” (244) and leveraged to justify the state’s “war on terror.” The state approved the construction of a church in honor of the martyrs in the village of ‘Aur, home of fifteen of the victims. Their bodies and the church that commemorates them function as an ambivalent “territorial sign of minoritarian identity and military protection” (241). The state’s authorization of Coptic inclusion has also led to the exacerbation of Christian-Muslim tension. State sponsorship of the martyr’s memories has inspired some backlash among Muslim neighbors, generating resentment and violence (247-48).

A crucial part of memorialization, Benedict Anderson notes in chapter 11 of Imagined Communities, is forgetting. If there is a surplus of memory in the case of the New Libya martyrs, other deaths are strategically silenced. One example will have to suffice. In the “Maspero massacre” of 2011, state forces killed 28 unarmed Copts of the Maspero Youth Union. The youth were peacefully walking to the national TV headquarters, trying to find ways to represent themselves independently from the institution of the Coptic Church. Their deaths do not count as acts of martyrdom. “Their omission from communal memory,” Heo writes, “indexes the vulnerabilities attached to those Copts searching for a sense of Christian-Muslim belonging unyoked to religious institutions” (245).

What we see in the radically different response to Maspero and Libya is what Heo, following Judith Butler in Frames of War, calls the “differential grievability of lives” (243), a difference that is determined largely by what is allowed to count as worthy of memory and what is consigned to forgetting in the name of forging a certain kind of community. In the case of Maspero, the Coptic Church aligned itself with the state in its forgetting of victims, seeking consensus with ruling powers. The Church disavowed the memory of some victims in order to determine the territory and terms of a certain form of community.

Heo’s book repeatedly shows the way in which devotion to the saints cannot be understood simply as a privatized affection for the holy figure, but is a site where the power of imagination and narrative in crafting particular frames of the holy helps conquer territory, define political fortunes and communities, and establish the boundaries of piety. Her account of contemporary Egypt resonates with my own work on thirteenth-century sanctity in the Southern Low Countries. In this context, lay women previously not seen as viable candidates for memorialization as holy figures—forgettable women—were advanced as saints by clerics through the creation of hagiographical narratives and political advocacy. The hagiographical representations of these figures (who manifested profoundly embodied forms of sanctity) were enlisted by the church to counter Cathar claims that the divine was necessarily immaterial (excluding the physical sacraments and the Incarnation). These theological defenses were used to underwrite military aims: the Lives written by Thomas of Cantimpré and James of Vitry called for Crusading efforts against Cathars. The depiction of the saint became a means of determining who counts in an emergent definition of “Christianitas,” the social body of Christ. The saintly body is not here only a synecdoche for the communal body, but is also a site of devotion that organizes the affections of the devout and sculpts their desire and memory in ways determinative of material realities, including the war on “heresy.” Seeking the generativity of anachronism, late ancient models of sanctity were recapitulated and repurposed for a new context.

However, as Heo shows, the memory of the saints is radically malleable, their futures never predetermined by their pasts; attempts by the state to enlist support for the war on terror through the sponsorship of the new Libya martyrs generated many unanticipated effects as they continued to signify multiple meanings and arouse very different allegiances for different communities—Muslim, Coptic, Evangelical, and Catholic. For Thomas of Cantimpré, insofar as his hagiography are works of propaganda, they are attempts to control just such malleability. However, even in this midst of this political project, his works demonstrate that saints remain in excess of attempts to quell their polyvalent, often ambiguous, potential. They are excessive not only because of the shaping power of audience expectations and the changing contexts in which their memory is taken up, but also because of a theological principle, recognized by Thomas, that insofar as a saint’s perfection manifests a divine plenitude that exceeds human attempts to shape or contain it, the narrative that re-presences it will never succeed at such attempts at capture, thereby keeping open the multiplicity of the possible afterlives of the saints, their exemplarity functioning to inspire forms of belonging and life together in ways that Thomas himself might have found perverse or unimaginable.

Different ways of telling the same story delimit different possibilities of inclusion even as memorialization entails a symbolic circulation that cannot be entirely predetermined at the outset. Heo hopes for change in the Egyptian political situation through the transformative solicitation of memory: “activating the memory of saints and martyrs, their appeal to millennia-long traditions point…to a set of deeply engrained sensibilities and landscapes that can retool horizons of memory and action, and hope toward common flourishing” (252). In other words, Heo is suggesting that communities might coexist and belong together differently depending on how narratives about saints are used by them.

This capacity for devotion to the saints to structure and make possible different kinds of community is not a form of anachronism—a melancholic nostalgia seeking revenge upon time—but rather a living, labile force of the present. If Heo argues that saints are not anachronisms, she is thereby making a larger claim about the persistence of religious traditions and communities of devotion across time. In the broadest sense, what Heo challenges is the secular assumption that religion itself is anachronistic. In fact, that opposite might be truer, namely that secularism is more truly anachronistic insofar as it is not in sync with the vicissitudes of time.

Heo’s work articulates the powerful potential of the (non)anachronism of the saints. This does not mean that Heo’s work on Egypt should be used to generalize about all other contexts. However, recourse to Heo’s work may help us to recognize the different forms of anachronism that compose many modernities that are of the time and above it, and thereby remember and tell stories that facilitate other kinds of belonging.

[1] For an account of the moral valence given to anachronism by historians, for whom it is a “mortal sin,” see Jacques Rancière, “The Concept of Anachronism and the Historian’s Truth,” The History of the Present 3.1, art. 3 (2015): 26.

[2] Heo shows how modern technology has, in this case, allowed sanctity to be demonstrated in a much more expeditious way than the labored means of hagiographical narratives, miracle accounts, and eye witness statements. ISIS recorded and disseminated video of the beheadings that show each of the victims speaking the name of Jesus. This video was used as proof of the martyr status of all 21 victims, and the typical 50-year period required by the Coptic Church before sainthood can be declared was not applied (240).

[3] Tertullian, Apologeticus, ch. 50. Quoted by Heo, 38.